What Colomendy meant to generations of Liverpool schoolkids

As the future of the North Wales campsite hangs in the balance, The Post explores an important part of Scouse social history

In a famous Inglourious Basterds scene, a British spy blows his cover with an un-German three-fingered gesture. Keen-eyed Scousers can likewise spot an undercover “Wool” or a “Plazzy” by certain giveaways — like wearing white socks, saying “ice lolly” instead of “lolly ice”, or having never been to Colomendy.

Rhiannon – AKA my Fairfield lady – says the latter sin will forever preclude me from the Liverpudlian afterlife (Shangri-Laa?) to which she and our children are bound. This is because Colomendy is a rite of Scouse passage, a memory which all true-born sons and daughters of the city share.

For more than eighty years, generations of Liverpool kids were taken on school trips to the holiday camp at Loggerheads near Mold. An all-purpose activity centre, Colomendy had canoeing, swimming, climbing, and other indoor, outdoor, and water sport facilities.

“I remember it being steep and muddy,” Rhiannon says when I try to interview her, confessing she only went for a day.

My mate Clare – the kind of County Road girl who’d never be seen dead in white socks – never went, either. “The thought of abseiling, canoeing, and generally living with my schoolmates for a couple of days seemed like Hell on Earth,” she tells me.

Having no luck with my own generation, I speak to family friend Sue who was a Liverpool schoolgirl in the 1960s. She says she missed the bus and never made it. Did anyone actually go to this bloody place?

Alright — maybe Colomendy isn’t integral to the Scouse identity. But back in January, when the other Liverpool paper broke the story that the camp was closing for good, an outpour of disappointment followed, and then a swell of memories across comment sections and social media. In an act of journalistic penitence, I decide to visit the site myself.

On the way to Mold, I think about how the heartfelt nostalgia that met the news of Colomendy’s closing was accompanied by another favoured Liverpool pastime: having a pop at the city council. In 2007, the council issued a 30-year lease for the site to Kingswood Colomendy Ltd, a subsidiary of Kingswood, a company which provides facilities for residential education. Kingswood going into administration precipitated Colomendy’s immediate closure.

The Lib Dems are now demanding that the council “works to reopen the site as a facility for our city's children, instead of selling it off for housing.” Their leader, Carl Cashman, posted on X: “The Labour council's failure to make sure Kingswood maintain the site now risks leaving council tax payers with a large bill to restore listed buildings that have been allowed to become derelict.”

In response, a spokesperson for the local authority told The Post that “council officers have been enforcing the satisfactory performance of the lease terms, primarily the issue of outstanding repairs.” They added that “no decision has yet been taken concerning the future of Colomendy. The site is situated within the Clwydian Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Therefore, any decision concerning the future use will need to be carefully considered against Local Plan policy in collaboration with the two adjoining county councils.”

But how is it that the Liverpool empire came to expand into North Wales to begin with?

In 1939, as war drums beat on the continent, the British government established the National Camps Corporation as a non-profit tasked with constructing and administering camps in the countryside. Thirty-one such sites were built across England and Wales for children from urban areas to be sent in case of German bombing, with the city councils often granted authority – for instance, Brownrigg camp school in Bellingham fell under Newcastle’s administration. Colomendy, designed to house Liverpool children in case of bombing, was placed in the city’s control, where it remains to this day.

Several of these sites are now derelict or disused. Finnamore Wood, built to house evacuee children from Redbridge in Greater London, became a young offenders’ institution before closing in 1996; it was demolished in 2023. Linton camp, once a haven for Bradford school children, lies decaying in the Wharfedale countryside. If this is the fate that now befalls Colomendy, a paradise never to be regained, it will mean an important part of Scouse social history is lost forever.

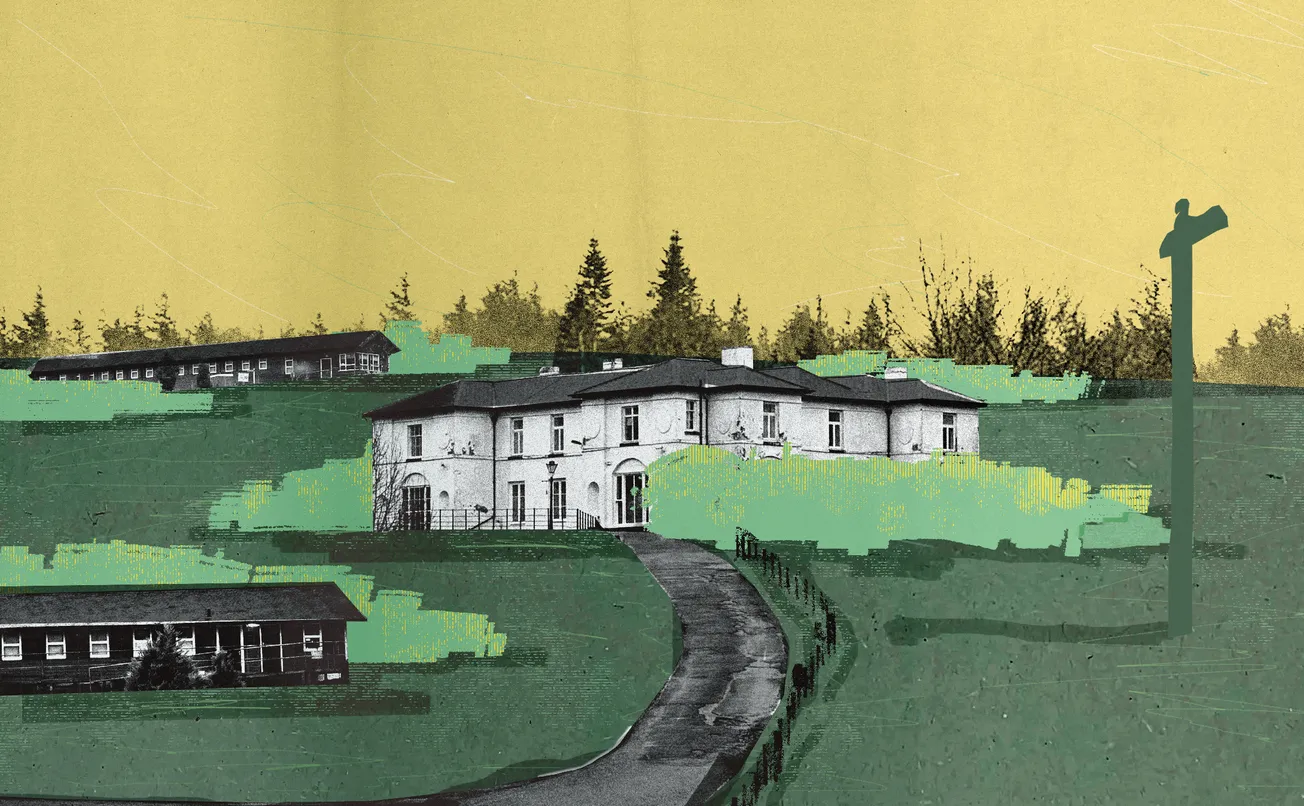

When I arrive, rain falls on the camp in long diagonal lashes. It’s strange to think I’m standing in an outpost of Liverpool itself. “Croeso I Colomendy”, welcomes a blue sign in front of a red brick wall blackened by mould and lichen. “Antur yn dechray yma!” says another: adventure starts here. Coniferous fronds shadow the path ahead, which leads to what look like the original Canadian red cedar cabins, doors and window shutters freshly painted green. Row of firs look down from a little hill behind. Apart from the verdant, rain-fatted grass and brown of the trees’ bark, the only other colours come from a totem pole maybe twenty feet in height. Faded blue, red, and yellow carvings twist up to the bust of an eagle on top, looking down on the abandoned camp with stern eyes and a hooked wooden beak. By the cabins, a signpost tells me we’re 33 miles from Liverpool. (And, helpfully, 1636 from Moscow.)

Not all of Colomendy’s history is happy. The first generation of children to come here were stricken by fear for their families’ safety. The blitz was so bad, the fires could be seen from thirty miles away; a BBC article from 2010 quotes Olwyn West: “Night after night we observed the glowing skies above our home town… We were all on tenterhooks.” Et in Arcadia ego.

Then, in 1951, an uprising broke out at the camp when 150 boys felt their tea was cleared away too early; they smashed crockery in the dining hall and threw cutlery on the lawn. "It was a first-rate riot," the camp headmaster told our now-defunct namesake.

As I’ve never been to Colomendy before, I’m surprised memories do begin to coalesce. In my first year of secondary school, we came to Wales on a residential trip, but to a place called Capel Curig. If I’d had the choice, maybe I’d have stayed home like Clare. I cringe as I recall capsizing two seconds into my first kayak launch, the ice-cold Snowdonian stream making immediate mockery of the “waterproof” boast on my clothing labels. Chattering teeth and classmates’ jibes, then a bronchial chest and a bollocking off my geography teacher when I handed in my traumatised report a week late: these are the things that probably made me want to write instead of attempting outdoor sports.

A light wind whips up the firs and rustles the smooth grassy hillside and then my coat collar, bringing me back to the present and Colomendy. I walk around for about half an hour, trying to picture the thousands of young visitors over the years running happily from the cabins up to the woods beyond the big white manor house, laughing and joking.

But the only sounds now are the chirps of sheltering birds and the occasional rush of traffic from the distant road. I feel exposed; observed, somehow. In time as well as space, I feel like a trespasser. Legally, I probably am, although the site’s status is up in the air: a council statement in January said it expects the lease to be returned forthwith. When asked for an update, a spokesperson told The Post that while the authority has “assumed responsibility for site security, care taking and other related matters, [there is] a legal requirement to formally bring the lease to an end in which to avoid any potential on-going issues. This will happen very soon.”

Back home, I finally get in touch with a few former campers. I speak to David, who attended in July of 1981.

“I’d have been 10,” David says. “I remember the big dormitory, and kids messing around. Then the teacher started talking about Peg Leg…”

Who was Peg Leg? “It was supposed to be the ghost of some teacher or staff member or something,” David says. “Anyway, everybody went quiet.” David remembers hearing knocks or bangs on the walls or floor in the night – presumably teachers reinforcing the myth of Peg Leg to prevent the kind of behaviour the camp saw thirty years before. But like Olwyn’s class ten years before that, David would end up worrying about people back home.

“While I was there the Toxteth riots erupted,” David says. “We got word back that it was civil unrest and bloody plastic bullets – they’d used them in Northern Ireland, but this was the first time on the mainland and all that palaver. It was sort of scary, to be honest.”

Judith was there for five days in the 1960s. She remembers the legend of Peg Leg too, but not being scared. “I loved it,” she said. “Going along the River Alyn, up Moel Famau...”

Judith remembers that children were often lured to the top of the Clwydian peak by the white lie of an imaginary chip shop – the Scouse version of a gingerbread house. (When Clare finally did climb Moel Famau in her thirties, it was because she was told there was a pub up there.) Judith’s class also visited a dairy farm, the idea being to give city children an idea of bucolic life. For many pupils over its eight-decade span, Colomendy represented their first time “abroad”, beyond the bright lights and dense streets of Liverpool.

“I remember [Colomendy] for being the first time I had seen the Milky Way in all its glory,” says Geoff Johnson, who went twice: once in primary school, and again as an art student at Liverpool Polytechnic. “Liverpool skies were very polluted in 1976.” His second trip also involved “a lot of trips to licensed premises, usually in the dark”: plenty of libated opportunities to see the galaxy in its fulsome splendor.

“A minibus took us from the office in Liverpool,” says Peter Longman, who was sent to Colomendy aged six or seven in the early 1960s to convalesce after a bout of meningitis. “I recall not understanding at all what was happening, children then just did what they were told.” Peter’s trip was a more austere time than Judith’s or Geoff’s reveries: he remembers toilet paper was rationed and the chocolate bars his mum sent him were confiscated and placed in a communal tray. “Memories are sketchy, but… Sometimes I endured my time there, sometimes I enjoyed it. I returned after a month feeling much better.”

The hardships were part of what made Colomendy a rite of passage. But its value was not just in physical assets, its sports facilities or handy proximity to hill, stream, and valley. For generations of children – even those who resented marching through mud or were terrorised by bumps in the night – this was an imaginative zone, an adventure not just in space but of vision. For some, it was the first time they could look back at their home city from an objective vantage point; for others, a unique opportunity to look outwards at the universe; either way, fresh concepts populated young minds like stars in a new firmament.

For me, books eventually fulfilled that purpose — the fantasy realms of Ursula le Guin and Alan Garner. These days, when only one in three eight to 18 year olds read in their free time, and travel within the UK itself is prohibitively expensive, perhaps cheap family flights abroad are kids’ main opportunities to get away. More likely, though, internet access and video games are the closest thing most young people get to a sense of their place in the world and beyond it, even if they’re just staring into electronic screens designed to hack our brains into mollified compliance. Is that what a childhood for Liverpool children will now become? Not that it’s a binary choice, but even if my time at a North Walian residential camp was unhappy, I think I’d rather bitter Welsh waters and lactic-heavy trudges up muddy slopes for my son than mere virtual escapism.

If Loggerhead’s blue remembered hills are to become a land of lost content, Colomendy has more than served its wartime brief to provide generations of children first with sanctuary and then with education. But the camp’s loss will also be a break with the past, with some of its amenities intangible and irreplaceable. Denied a clear vision of its future, Liverpool is too often imprisoned by memories both good and bad. With Colomendy, Liverpudlians will once again be left asking questions of an institution’s custodians, until there’s nobody left who remembers it at all.

Comments

Latest

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

What Colomendy meant to generations of Liverpool schoolkids

As the future of the North Wales campsite hangs in the balance, The Post explores an important part of Scouse social history