When Liverpool ruled the world

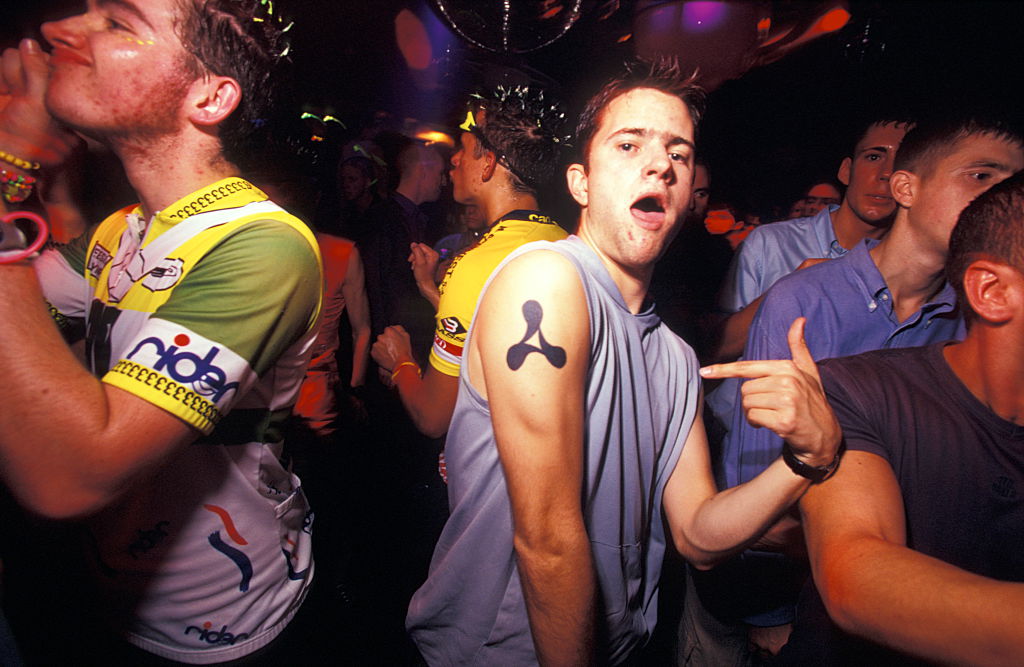

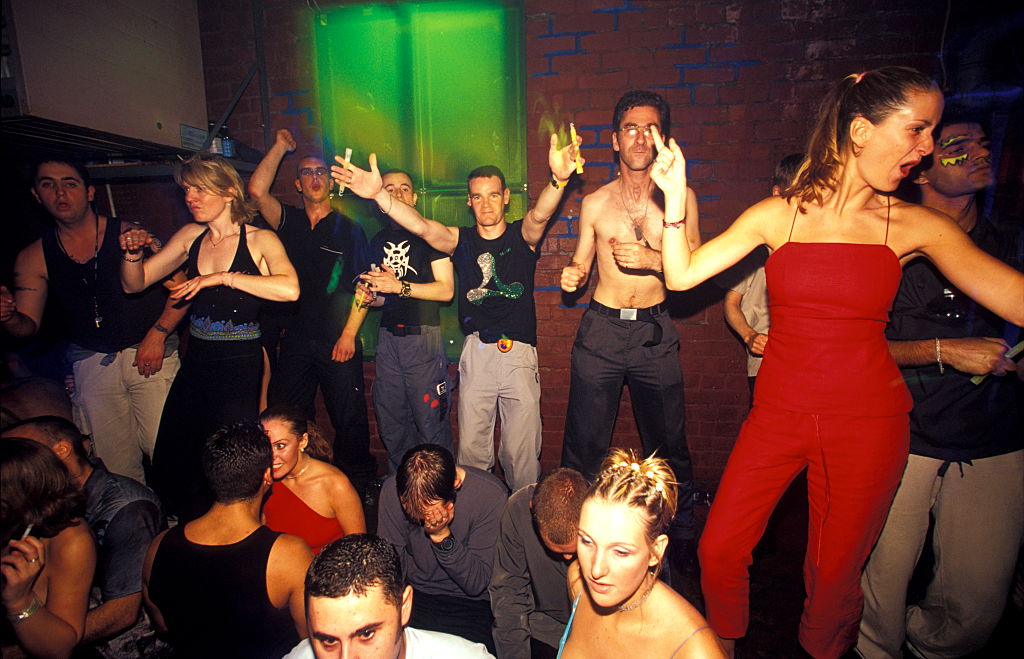

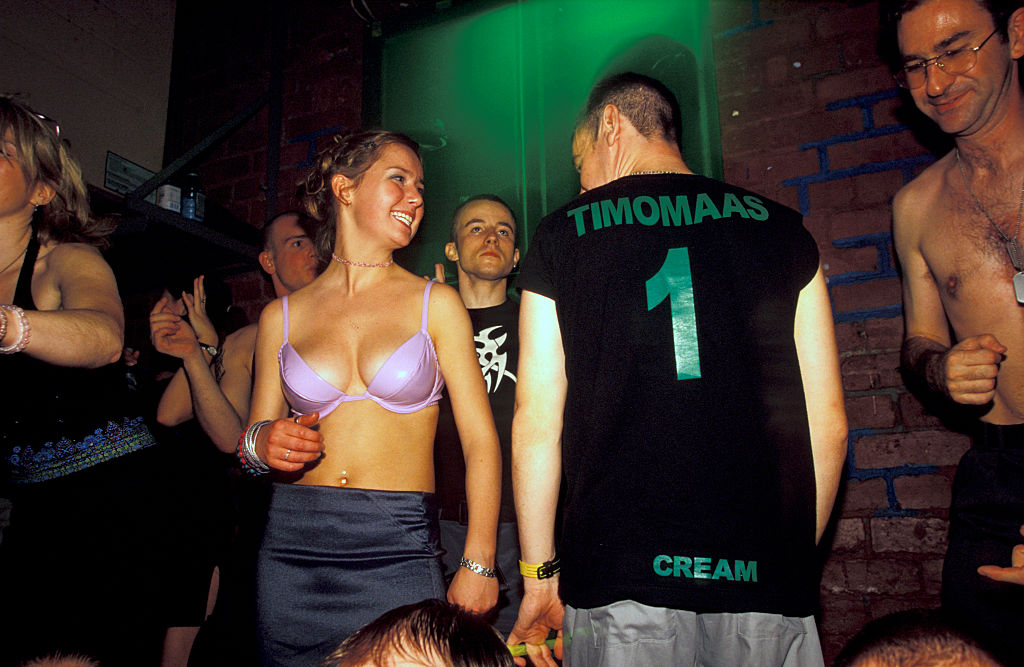

The magic of Cream in 1995 and beyond

I’m on a Ski-Doo safari in Svalbard, a rocky scatter of islands in the High Arctic. It’s 1995. For a moment, our guide tells us, we’re probably further north than anyone on the planet. We track south to visit an international team of scientists who have spent winter here, prising ice cores from the permafrost. I get chatting to a student from Tromsø in Norway. “Where are you from?” he says. “Liverpool,” I tell him.

“Oh wow. Have you been to Cream?”

This is what happens when you’re from a city that creates something like a phenomenon: the world can hear it.

I’m thinking about that chance encounter as I write this on the eve of Creamfields, and the club’s 30th anniversary this October. What would have happened if I'd arrived 30 years later? “You’re from Liverpool? Oh wow. Have you snapped up any lucrative buy-to-let investments on those apartments in Wolstenholme Square?”

I’m not saying my youth was any better, or worse, than yours. That would be ridiculous. But I did have the good luck of my younger years coinciding with a moment when the city thought it could do anything, and when for a short dazzling period, it did. The supermassive black hole at the heart of everything? Cream.

Like Game of Thrones and fidget spinners, it’s a cultural high watermark that no one talks about these days. But Cream’s history matters, because it shows what can happen when youth culture is allowed to do whatever it needs to do. No councillors monitoring sound levels, ready to shut down venues to score a few votes from fitful sleepers. No newly vibrant neighbourhoods sold off to shady developers to capitalise on — and erase — the very thing that put the postcode on the map.

But this isn’t a story about how it all went wrong. It’s a precious artefact from a time when everything was right.

When Cream ruled the world, the city felt like a long-dormant beast stirring from its slumbers. It was a hypnagogic state of positivity and possibilities; a time when it felt like everyone was young and everything was new.

As the 1990s moved into cruising speed, warehouses became indie shopping malls, bars became baa baas and there was a cluster (an actual cluster) of record shops at the top of the town. Kids from Aberdeen to Penzance were hastily scribbling their application forms to John Moores University in the hope of securing a space. Not in a feverish desire to complete a Sports Science Degree, but to be a witness. To be a part of Liverpool’s metamorphosis.

Because something had shifted in the city’s shared consciousness. We went from the hard-done-to People’s Republic of Liverpool narrative and started dancing to a new tune, one of outward-looking optimism and swagger. It was Cream that helped remind us not just that we could dance, but that we could walk tall too.

Soon there was FACT and the Biennial. Before long, strange new skeletal forms started to loom over the city — the cranes that began to reshape our future. It was a thrilling forward propulsion that would inevitably lead to our Capital of Culture coronation. No other city stood a chance. Of course we are the capital. Just look at us. We’re world class.

And let’s leave the story there. Because, as I say, this is about a time when everything was right.

Cream’s Phazon sound system didn’t just shake the rafters, they shook up the world of the bedroom gamers too. WipEout — the massive made-in-Liverpool Sony franchise (when Sony was a massive Liverpool presence) — changed the face of gaming. Its soundtrack? A resolutely made-in-Liverpool mixtape of block-rockin’ beats inspired, so the developers proudly confessed, by messy nights out clubbing in Liverpool. A little Chemical Brothers here, a side order of Born Slippy there.

I know where they went. Because I was there too. A night in Cream would start in the afternoon. A Perfecto Fluoro CD and some Smirnoff Ice to loosen up my anxious feet. Because I wasn’t born a clubber. Cream made me do it.

I’d meet my clubbing partner, the Chief, at Central Station and head to the newly sandblasted Concert Square for drinks in Kiosk. Or just down the road in the Beluga Bar if it was raining.

The Chief. Welder by day — wife, two young daughters in Bromborough. But from 9pm every Saturday from 1995 to 2000, he was the most important person in my life. And me in his. We met in Nation — on a Friday nighter called Club 2000 (because we were too scared to go to Cream), and made a pact to go together the week after, and share half a tablet.

Easy does it.

It was a promise set to shape the rest of our Saturdays for the next half a decade, and our August bank holidays at the old Speke airfield for a few summers after that. We’d not speak, or meet, outside of these times. Why would we? It was an all or nothing kind of relationship. We had nothing in common. Apart from Cream.

In the queue that lassoed around MelloMello and down Slater Street we’d meet first timers and old hands, discuss the night’s highlights gleaned from Mixmag listings: a three hour Annexe set from Nick Warren, a blinder from Seb Fontaine or an object lesson in amyl house from Ed and Tom themselves. Vitamin supplements might be prescribed. Higher States of Consciousness hinted at. Nerves eased.

Within, crowds would gather under the TV monitors by the long bar to check who was on where. We’d perch on those orange blobby sofas that looked like they were made from papier-mâché to plan our excursions into the Front Room, the Annexe and the Courtyard, occasionally going our separate ways, getting lost and reuniting to tell of our tales in the humid tropics and dense thickets of the club’s innards.

I’d be in my sweaty Hooch top, he’d be in his lurid orange Tommy Hilfiger shirt (accompanied with half a bottle of lurid Tommy Hilfiger aftershave). Both with grins as big as Paul Oakenfold’s bank balance.

When I think of those nights now, a quarter of a millennia ago, I’m struck, first, by a still-acute pain of separation. The Portuguese have a word for it: saudade. It’s that profound, intense and melancholic longing for lost things.

What things? Innocence? Hardly. Not if my memories of being in the DJ booth with the Propellerheads trying to score are anything to go by. Youth? Maybe. But I don’t have the same intensity of feeling for the other six nights a week I cheerfully wasted in my 20s and early 30s.

It’s a sea of hands in the air, clasping onto the raised palm of the stranger next to you, while some trancey mashup of Killing Me Softly morphs into Loving You More by BT. Remember this moment, I thought to myself. And I do.

A lad from Barnsley is off to join the Signals Corp of the Army on Monday; his last night of freedom. “What’s signals?” I ask. He grabs my hand and taps out morse code rhythms to Shine by the Space Brothers onto his chest. I get it. We hug. Have a good night, mate.

A girl from Swansea who’d shaved all her hair off except for a vivid green Cream logo of stubble, wondering what they’ll make of her in the solicitors’ office on Monday. And, at the same time, not giving the slightest of fucks about it. I have no doubt she’s running her own practice of kick-ass litigation lawyers now.

The Full On all nighters where time stood still and synapses melted. A six hour marathon ending with this twisted, scuzzed up groove called Da Funk by some upstarts called Daft Punk. The Chief didn’t get it. Too slow. He only had one speed: 128 bpm. But I ate it up for breakfast before being spat out, blinking, into a new day.

Every new connection I made in that shanty town of corrugated iron and breezeblock was a friend for life. But we knew we’d never see each other again when the music stopped. We congregated in the half light, in those beaten-up back alleys, on the precipice of something. We didn’t know what it was, but rushed headlong towards it, together.

From the start, Cream refused to comply with the Pretty Green Eyes Scouse House rule book. It never put a donk on it. Much is said about how Cream brought LTJ Bukem and drum and bass to the city. But, more than that, it welcomed 4,000 people every Saturday night. Every one of them fell in love with Liverpool, and told their mates.

We’d pay a media agency called Tortoise Creative to strategise a viral marketing campaign instead these days. It would be an embarrassment. But they’d screenshare the metrics on Zoom and everyone would leave happy, thinking that they’d experienced real life.

When Cream hosted its final night in 2007 some said its ambition was its undoing. It got too big for its boots, and forgot where it came from. They’re the same people who no doubt think it’s fine for Liverpool Football Club to have global ambitions and spend millions, but a jumped up disco should know its place. Superstar centre-forwards are an investment. Superstar DJs are an indulgence.

I’d say 70,000 ravers in Daresbury this weekend might think differently. Not to mention the hundreds of thousands from Chile to Hong Kong, Ukraine to Brisbane that Cream turned into a little corner of Liverpool for the evening.

There will always be an energy source freely available to tap into in this city. I genuinely believe that. Sometimes, when our leaders prioritise personal prosperity over the city’s ascendency, it’s a seam that’s forced deep below the ground. Sometimes you can feel it pulsing through the streets, like ice water through your veins; an electrostatic charge, there for the taking. Cream tapped into that forcefield, amplified it and reflected it back at us.

It’s an energy that will never issue forth from an artist’s impression of a penthouse flat. It can’t be coaxed into a regeneration scheme, or burst out from the specials board at Gino D'Acampo's. And no matter how hard it tries, Visit Liverpool can never build a social media campaign to summon it from the pavement cracks.

But it doesn’t matter. It will ignite again in some forgotten hinterland, in an unloved space, when the city’s back is turned. As it did at the Cavern or Erics, Chibuku or Voodoo, Garlands or Sonic Yootha. And the city will start to pulse again.

Last time I saw the Chief we bumped into each other in B&Q. He was buying grout. I was hunting down a bath plug. It had been about ten years since we saw each other. We both grinned like kids.

“We’ve got one more rave left in us,” he said. “Don’t ever delete my number.”

“No way, Chief. As if.”

Where that long overdue reunion will be, I’ve no idea. But you’d better watch out. Because that Hooch top is ironed and ready.

Cream might well have been the city’s last huge pre-internet sensation. There are no videos of it on YouTube, no camera phone images to share. Precious little proof that those nights ever happened at all. Nation, Cream’s Wolstenholme Square home, has gone forever. Evaporated like some mythical, half-forgotten wormhole.

But that energy? It’s not over — not over yet.

Comments

Latest

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

And the winner is...

When Liverpool ruled the world

The magic of Cream in 1995 and beyond