Toxic air is choking Merseyside

'If you can imagine swimming in mud, that's what it's like breathing in this part of the city'

Merseyside has never been famed for its clean air. You probably have to go back to the pre-industrial days to find a time when the air in north Liverpool or south Sefton, particularly along the docks, was anything close to fresh. During the First World War, the poet Robert Graves said the metal buttons of his uniform were corroded by the thick industrial fumes of Litherland. “I used to sit in my hut,” he wrote in Goodbye To All That, “and cough and cough until I was sick.” Were he alive today, Graves probably wouldn’t jump at the chance to come back.

Our air quality is so bad that, according to one study, around 1,000 deaths every year in the Liverpool City Region can be linked to pollution. That same study, carried out by researchers from King’s College London, found that the lives of local children will be shorter by up to five months. Some of these statistics bear re-reading. Our research has placed particular emphasis on a stretch of dockland between Kirkdale and Seaforth, owned by The Peel Group, Merseyside’s billionaire landlords. We’ve uncovered new data about the air quality of our city, and have tried to find its potential origins in the port and the infrastructure that serves it. There is no simpler way of putting it than this: the toxic air of Merseyside is killing us.

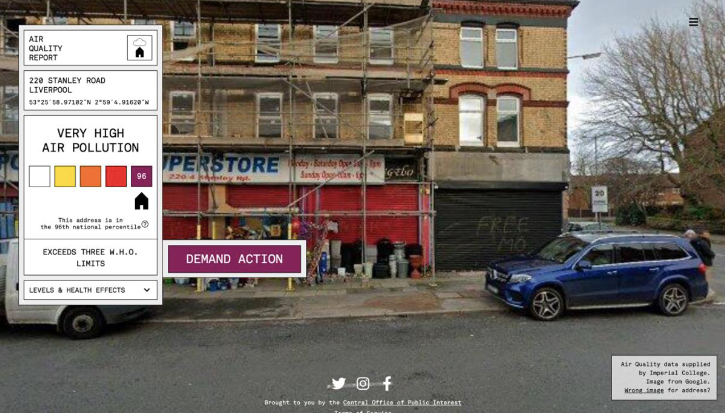

Let’s start with the facts: the air in some parts of Liverpool is terrible. According to air quality data supplied by Imperial College London, there are parts of Kirkdale, a residential neighbourhood abutting the docks, that have such dirty air that they rank among the worst addresses in the UK. On Stanley Road, the high street running through the neighbourhood, the air exceeds safe limits set by the World Health Organisation for three pollutants: PM2.5, PM10 (both known as different types of particulate matter), and NO2 (commonly known as nitrogen dioxide). PM2.5 is the pollutant that causes the most concern: it is commonly produced by vehicles and smoke from fires. Its particles are invisible to the naked eye and small enough to pass through the lungs, causing illnesses such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, strokes, lung cancer and dementia.

But it’s not just that the air here is toxic, it’s also poorly understood. While nitrogen dioxide levels are tracked across the city, the only ongoing official measurement of particulate matter occurs in a government-operated station in Speke. Why does this matter? North Liverpool wards like Kirkdale, Everton and Walton sit at least eight miles from that monitoring station, meaning the reality of pollution in those neighbourhoods is not accurately reflected in the data. Until we understand the air we’re breathing in, what hope do we have?

Liverpool City Council told The Post that they measure all of the pollutants they are legally required to and have several monitoring stations around the city, including a new one recently set up in Walton Vale. There are also two official measurement stations geographically nearby within the border of Sefton.

Swimming in mud

We first became interested in this story following contact with a man called Leo. Leo had been born in Liverpool, but had moved to the Philippines with his wife a number of years ago, only to return in 2013. When they got back to England, Leo and his son William — now aged 10 — moved into a property in Kirkdale through a housing association. At the time, they were pleased to be back. But what has followed has been a ten-year nightmare.

William has a terminal illness making him susceptible to respiratory problems. As a father, Leo was eager to do anything he could to try and improve his son’s quality of life, and he started to become concerned about the quality of air in the area. “I just noticed the burning on the scrap yard down on the dock was real bad — black soot, and it was coming into the house and everything else that comes from down the docks,” he says.

It’s a story many families in Kirkdale or the surrounding neighbourhoods will recognise; plumes of toxic smoke from burning scrap yards, chemical fumes on the docks infesting their family home with “black soot” and the wagons that roll along Stanley Road which never seem to stop. “You know it's not good because you can smell the difference when you're somewhere else with fresh air," Leo adds.

Intrigued to uncover more, he started looking into the matter himself. He soon discovered that the council had got rid of the two closest air quality monitoring stations a few years prior — one in Queens Drive and other the city centre — measuring particulate matter. The only station that existed was miles away in Speke. Suffice to say, he doesn’t have a kind word about the council.

Making over a hundred trips to the hospital since living in Kirkdale due to his son's ongoing health problems, Leo eventually met paediatric respiratory specialist Dr Ian Sinha at Alder Hey. Sinha provided them with an air monitoring system to put in their home, the results of which were so alarming the doctor sprang into action, providing Leo with a medical report advising his family to “move out of the area to increase the longevity of his son's life”. Leo pleaded with his housing association who initially failed to act. It was only when Dr Sinha wrote directly to them begging to have them rehomed that his voice was heard.

Leo is upset that nothing was done at the time to warn him of the appalling levels of air pollution that blight north Liverpool. Given his son’s illness, the severity of the consequence is amplified to tragic extremes. “For me, it has taken years of my kid's life,” he says. “Because if I'd have known what the pollution was like when we got offered the house in this area when we first came back to England, I wouldn't have taken it." And he uses a disturbing metaphor to describe air quality in Kirkdale: “If you can imagine swimming in mud, that's what it's like breathing in this part of the city.”

This isn’t all anecdotal, Leo’s account is very much backed up by the data. An air pollution awareness campaign from the Central Office of Public Interest has mapped out pollution levels at individual addresses in the UK's most comprehensive air quality study. Their website addresspollution.org shows areas such as Kirkdale exceeding World Health Organisation (WHO) limits for three pollutants, with PM2.5 more than doubling the current limit. Despite LCC’s 2022 Air Quality Annual Status Report stating that particulate matter levels across the city meet the WHO standard, this looks far from the case for the industrialised wards of north Liverpool.

What’s more, an article published last year by Asthma + Lung UK, written by Dr Rob Barnett — a GP of 30 years in Liverpool — outlines a shocking near 12-year difference in life expectancy across only a six-mile area in the city. The average male life span in Childwall is 83.1 years. In Kirkdale ward, it’s 71.6. Barnett argues the drastic differences in pollution levels is a factor.

A burning issue

From Leo’s house on Fountains Road in Kirkdale, you’d only have to walk about 15 minutes to reach land owned by Peel, whose historical and monumental transformation of Liverpool's docklands looms large over our story. To many, Peel’s lofty ambitions for the docklands have serious negative trade offs, with their development strategies and the expansion of heavy industry causing enviromental concerns. Residents we’ve spoken to say the air quality in the area has worsened, with some even leaving upping sticks and moving away as a result.

Lethal, toxic air that is driving people from their homes, tearing apart communities and forcing distressed residents to combat the problem themselves.

Take Norton’s Metal Recycling Facility, located on Regent Road, as an example. According to the north Liverpool residents we’ve spoken to, this facility — with its mounds of discarded iron and steel — has a history of polluting Kirkdale, with accounts of metal dust and toxic fumes from fires on the site wafting into local homes and stifling the quality of air. Such accounts are nothing new, this has been part and parcel of living in the area for decades.

And still, the problem isn't going away.

Three years ago the British Heart Foundation released a video on Facebook alerting Liverpool to dangerous levels of PM2.5. One comment on the video states: "I live near the docks there is hundreds of cars and lorries daily going in and out my front door is meant to be white, but it's black soot all over it". And another: “Shut down that car metal scrap company on dock road .... stinks and toxic!”

In 2021, Mersey Docks and Harbour Company (MDHC), a subsidiary of Peel, got permission to infill the Canada Dock on Kirkdale’s waterfront. In doing so, Norton's facility was able to expand its operation in plans that anticipated a staggering 50% increase in output. Liverpool City Council decided the expansion required no Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in addition to the MDHC’s Environmental Report to measure the potential impact. The plans were permitted in February 2021, even though just three months prior, in November 2020, 100 tonnes of waste went up in flames, causing authorities to keep windows closed and avoid the area.

The council told The Post that an EIA is “a very specific process which is needed only for certain types of development,” and that the impacts here were not sufficient enough to trigger an assessment. They said that environmental matters were addressed in the report to the planning committee.

In a planning statement submitted by MDHC it was stated that “measures are in place to avoid pollution and nuisance,” but fast forward to 27 September 2021, and another massive fire broke out on the site. An emergency motion was then passed for the council to create partnerships with a number of relevant agencies to investigate. In March the following year, a meeting reporting the Environmental Agency and the fire service site inspections of Norton's scrap yard revealed shocking health safety hazards that required reducing waste piles by more than half.

After revised measures were implemented, a report noted that Norton had undertaken significant improvements. Yet two months later, on 19 May 2022, another fire broke out in the facility, so vast it required six fire engines to put out. It was reported the fire could even be seen 20 miles away. Whatever measures had been put in place clearly weren’t working.

Norton explained that many fires in their industry are caused by “lithium-ion batteries that have been left in waste electronics when they are thrown away,” and urged the public to recycle responsibly. They told us that they “go above and beyond” industry standards to reduce fire risks “including installing thermal cameras, carrying out weekly fire drills and manually sorting through every load tipped at our sites to remove lithium-ion batteries where possible.”

They added that they comply with “very strict site regulations and [operate] under an installation permit issued by the Environment Agency for the processing of waste electricals and scrap metal” and that they achieve a “95% recycling rate on all of its materials processed through [their] shredding operation”, on top of contributing heavily to the local economy (at Norton’s request, we have printed their statement in full here).

This isn’t only a Kirkdale issue, of course. It’s a similar story just over the border in Sefton. Sefton Council's Air Quality Report 2022 shows the area around Bootle’s Millers Bridge — which sees heavy industry and HGV traffic congestion — exceeding the recommended limits for both PM10 and nitrogen dioxide. Data from local monitoring stations shows daily levels of PM2.5 tripling WHO recommended limits throughout 2022. Further studies in 2019 show that 100% of schools and GP surgeries in Sefton are in breach of WHO guidelines for PM2.5. That’s right, 100%.

As you look down the stretch of docks, you see fuming chemical factories and rusted mountains of scrap metal. EMR Liverpool Alexandra Docks' 38-acre metal recycling facility has a history of criticism from Bootle locals affected by black smoke pollution entering their homes and metal dust covering streets. Residents living on Church Walk in Linacre Ward, in plain sight of the gigantic scrap heaps, fear it's damaging their health. A mother tells The Post how her severely asthmatic son gets flare ups from metal dust blowing into the house: “We had a Dyson air purifier, which checks the air quality, and it's always in the highest.”

In an incident reported in May 2020, the entire estate was engulfed in a cloud of metal dust resembling something like an orange hellscape. This sort of thing, the mother says, is an ongoing occurrence, along with loud explosions from batteries left in cars, that — when crushed — shake the foundation of their home.

EMR Liverpool Alexandra Docks told us that they provide a “sustainable way to recycle their end-of-life material”, that all of their facilities hold environmental permits and that “Liverpool Alexandra Docks facility is fully compliant within the thresholds set out in our permit”. They said they continuously monitor their operations in line with permit requirements. They added that each year, the materials they recycle in the Liverpool region “save over 2 million tonnes of Co2 compared to virgin ore.” They are also committed to becoming a net zero business by 2040 and have invested £16 million into their Liverpool facilities in recent years, including low-carbon technologies.

But the mother is clearly upset. "And Norton's keep on having fires. I'm thinking, what about these toxic fumes? What are we breathing in? Are we going to have cancers in 10 years?" She reels off a list of preventive measures she’s tried to save her son’s health; air purifiers, HEPA filters, dehumidifiers, and so on. All have ultimately proven futile.

It’s not hard to see her concerns. Linacre Ward has the seventh highest COPD (a deadly respiratory condition directly caused by air pollution) hospital admission rate in the UK. It also has the second highest overall hospital admission rate. “We've tried everything,” she says.

Splintered Sefton

In few places across the region is the conflict between Peel and residents as pronounced as it is around Rimrose Valley in Sefton. For the past six years the massive 3.5km country park and valley — which forms a border between Crosby and Litherland — has become the dominant political issue in the area, prompting bottom up campaigning on a mighty scale.

Communities have split. Podcasts have launched.

In 2017 a proposal was put forward by National Highways for a dual carriageway through Rimrose Valley. Talks of such a proposal had been around since the early noughties, and the intention was to create better access to Peel’s Port of Liverpool and divert the heavy traffic that currently exists on Church Road (the A5036) on the new bypass. A combination of factors — both environmental and financial — have caused delays and the bypass is on hold until at least 2025. Regardless, residents have been in uproar.

From an environmental perspective, it was Sophie’s choice: increase pollution on an already congested road or obliterate the remaining greenspace on Rimrose Valley. One phrase that crops up in my conversations with residents is “sacrifice zone”. The suggestion is a big one: that the needs of the area and its community have been discarded in the name of commercial interest. Once a treelined boulevard, Church Road is now permanently crammed full of HGVs heading in and out of the docks, dispersing toxic fumes as they go.

Data sourced from National Highways in March 2023 estimates around 13 million vehicles a year on the road, not counting the spillover onto small residential streets.

And if that’s not bad enough, between 2010-2015, the standardised emergency emission rate for COPD (a deadly respiratory condition directly caused by air pollution) in Litherland was 161, compared to 100 for England. Between 2015-2020 Litherland saw a frightening increase to 249 each year. That puts it almost 150% above the national average.

According to residents, the surge in traffic since The Port of Liverpool's expansion has created air so dirty they can’t open their windows, with the added bonus of the deafening noise of industrial clanging on the docks. Another community member believes the early studies on the future environmental impact of the port's growth were ignored.

For example, an Environmental Impact statement written in 2005 on behalf of Peel’s subsidiary, The Mersey Docks and Harbour Company, seemingly “disappeared” from council records only to turn up years later, after a mysterious man from Waterloo provided the campaigners with a printed copy of the mega 873-page report.

One Church Road resident states that the 2005 report makes unrealistic claims. He cites the example that the report argued that “air quality impacts of the proposed development will be negligible,” while simultaneously estimating an enormous daily increase in HGVs. There’s a belief that — had the public been able to view these documents at the time — it would likely have triggered massive opposition.

Peter Moore, Sefton Council’s Head of Highways & Public Protection, told us the council is “fully transparent about its air quality monitoring” and “recognises the health impact of poor air quality on our communities”. He told us that air quality in the “vast majority” of the borough was recognised as good, but that four localised areas in the south with higher nitrogen dioxide levels had been identified and declared “air quality management areas”. The council has been giving specific attention to improving air quality in these zones.

Mo Walker is a local living on Church Road and an independent candidate in Sefton’s upcoming elections. She’s opposed the plans since they were announced. Speaking to Mo, it’s clear that the two-decade battle in her neighbourhood has been exhausting. Working in a local nursery, she fears for pupils' health: “Last year, we had 27 children using inhalers, and when you map it out, they live on or around Church Rd — I'm talking about two, three, four-year-olds.”

Walker believes the Council and MPs should have taken a different approach from the start. Rail network options — as outlined in the initial 2004 Council Report — were her preference, and options she believes the whole area "would have all fought together" for.

Peel’s director at the Port of Liverpool, Phil Hall, contended that while the current access road is “important for the hundreds of businesses and thousands of people who depend on the Port of Liverpool for jobs and the supply of goods,” over 80% of the traffic on the route is made up of private vehicles, not HGVs. He added that the bodies involved — National Highways, Sefton Borough Council, businesses and the local community — “need to work together to find ways of successfully managing transport in the area”.

But Stu, the lead campaigner for Save Rimrose Valley, believes Peel's involvement in the road scheme has deliberately been obscured. Campaigners filing FOIs were able to uncover ongoing supportive lobbying by the firm for the road, for example. Stu, suffice to say, doesn’t have the rosiest view of the future for his area. "It's the reality of what happens when you allow big business to expand,” he says. “It worries me."

Political abandonment

A documentary created in 2022 called Cellular Vessel, supported by Dr Leo Singer, a lecturer at the University of Liverpool, examined human biorhythm theory and its connection to environmental justice issues. It uses The Port of Liverpool, particularly in light of the 2016 international Peel terminal opening on Seaforth Docks, to highlight what it terms “political abandonment" and "a whole range of environmental stressors that generate rising levels of premature death and multimorbidity".

Political abandonment is a strong turn of phrase, no doubt, but Singer is sure of it. He describes how older residents in places in Sefton like Seaforth and Litherland — the ones who remember the tree lined boulevards, and who watched those boulevards gradually turn to dense rows of HGVs — become severed from their sense of place. He calls it “slow violence”, because it doesn’t happen overnight, but those who witness it do so with a feeling of helplessness. Now, those residents are left with one of the two COPD hotspots on Merseyside. “Communities need to unite behind one strong demand,” Singer says. “If we want a chance to achieve real environmental justice. Otherwise, we will just perpetuate the history of marginalisation of working class people in Liverpool.”

Hall told us the port “takes its environmental responsibilities seriously” and is proud” to be recognised as an industry-leading operator when it comes to reducing carbon emissions”. They pointed to a number of environmental activities undertaken by Peel including a commitment to net zero by 2040, a project to install up to 35,000 solar panels across their Liverpool port estate and the fact that 88% of their plant equipment fleet runs on hydrotreated vegetable oil and 83% of their vehicle fleet is electric, contributing to reduced carbon emission and improved air quality.

Leo and his son will soon be leaving Kirkdale, thanks largely to the influence of Dr Sinha. They’ll be glad to leave the docks behind, as well as all the accompanying scrap, fumes, skip yards, siloes, chemicals that waft off the ships and wagons that bound through the local neighbourhoods. Indeed, the move can’t come soon enough. “It gets in your skin, it gets in your clothes, it is just no good for adults, never mind kids,” he says. He’s not sure what the new neighbourhood will bring, but none of the minutiae matters too much. Leo can’t wait for his son to live in a place where breathing in isn’t a dangerous act.

Comments

Latest

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

The Pool of Life

Toxic air is choking Merseyside

'If you can imagine swimming in mud, that's what it's like breathing in this part of the city'