The Shepherd of Anfield Road

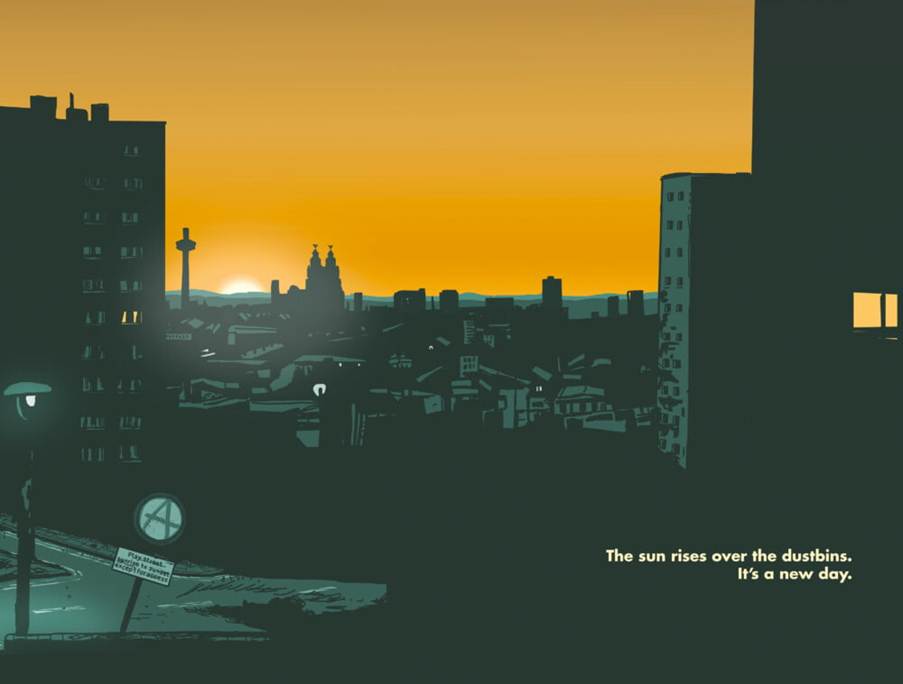

‘The sun rises over the dustbins. It's a new day.'

Dear readers – A very happy Friday to you all. Today’s edition is dedicated to the extraordinarily impressive feat that is Anfield Road, the semi-autobiographical graphic novel set in ‘80s Liverpool that took author and illustrator Chis Shepherd four years to bring to life. Laurence chats with Chris about his foundation year at Liverpool Poly, his artistic influences, his comfort across a variety of genres and mediums (“Me, I just wanted to tell stories”), and why, even though he now lives in London, Liverpool is the best city in the UK. Hear, hear.

But first: some news about a beloved micro-brewery going into administration, more delays at the Tate, and the great unveiling of Sandhills station…

Editor’s note: Today’s post is free to read in full (please go ahead and share it with a friend!) but tomorrow morning we will be dropping our next Post investigation — one of our biggest to date — and that one will be paywalled halfway through. As we go through final details with our lawyers and editorial team this afternoon, we would deeply appreciate your support in the form of a paid subscription. You’ll get to read the full explosive story first thing tomorrow morning and support us in doing this kind of deeply-researched and long-reported work. Thank you.

Your Post Briefing

After much anticipation, the metro mayor, Steve Rotheram, has unveiled a modification at Sandhills station to incorporate a “fan zone” for people travelling to and from Everton’s new stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock. The result of four years of planning between the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority and their partners Merseyrail, the new structure so far seemingly consists of a series of metal crowd control barriers arranged in rows across a tarmac space. “We are investing in the fan zone to ensure a smooth and reliable match day experience for fans,” Rotheram posted on X. “By doing this, we're prioritising fan safety, while making sure travel is quick and reliable.”

Thoughts on Sandhills and the new stadium? As always, let us know below.

In other redevelopment news, the reopening of the Tate Liverpool has been postponed by a further two years. Originally closed in 2023 for a refurbishment that was expected to take two years, the Albert Dock gallery will now not reopen until 2027 at the earliest. According to the BBC, the Tate Liverpool has only raised £17.85 million of the £29.7 million needed to complete the transformation; £10 million of this came from the government’s levelling up fund, while £6.6 million came from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. “We are close to achieving our goals,” said Helen Legg, director of the gallery. “This exciting regeneration will ensure it remains a cultural beacon for years to come!” tweeted Steve Rotheram as the metro mayor visited the site on Wednesday.

And some very sad news for craft beer lovers: Carnival Brewing Company, the award-winning micro brewery and taproom, has fallen into administration. LiverpoolWorld reported on the news, pointing out that Carnival was highly regarded by beer lovers, amassing a Google rating of 4.8 out of five stars (with five stars coming from Shannon, who’s particularly devastated by this turn of events). "I can confirm that we have been appointed as joint administrators for Carnival Brewing Company,” says Paul Stanley, partner at Begbies Traynor. “Many small, independent businesses are facing difficulties at the moment and despite establishing a number of trade and individual customers in a competitive industry Carnival has been unable to find a buyer and has been placed into administration. We are working closely with creditors and directors to support on next steps. This includes seeking buyers for the assets of Carnival via an auction which will be held on 26 February."

I have a deep and abiding love for comic books. Strangely, considering the close association, I’m not especially fond of superheroes – I’ve always resented the genre’s stranglehold over the medium in much of the Western world. As comics legend Warren Ellis once put it, their pervasiveness is analogous to every bookshop on the planet having ninety percent of its shelves filled with nurse romance novels.

But British comics were always different. After some exposure to the Beano, the Dandy, and the charming – though sometimes chilling – works of Raymond Briggs, my mind was blown at a young age after (literally) cracking the aged spine of an uncle’s risqué and cape-free Action annual, the predecessor to punk-comic newsstand mainstay 2000 AD – which I then also devoured. At some point, another uncle started buying me Viz annuals every Christmas, which probably had a bigger influence on my sense of humour than anything else.

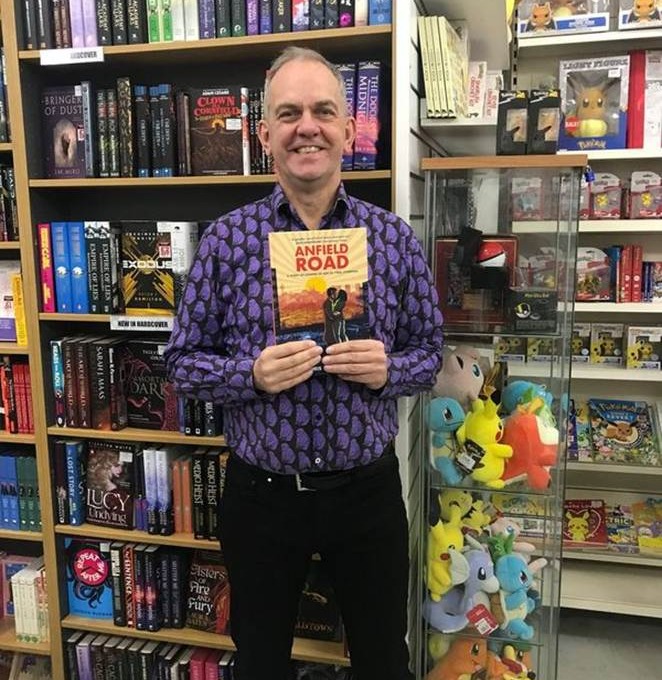

So last year, when I heard someone had written and drawn a comic book about Liverpool – with nary a masked avenger in sight – I had to pop up to Forbidden Planet’s Bold Street branch and get myself a copy of Anfield Road.

Titan Comics have published an impressive object, with a lovely heft and matte gloss, its hardback covers emblazoned with endorsements from Anfield comedy legend Alexei Sayle and Jesse Armstrong of Succession fame. The artist behind the project, Chris Shepherd, is most famous (to me) for animating the hilarious and unnerving 43rd World Championship Stare-Out sketches for BBC Two’s Big Train and sections of Chris Morris and Charlie Brooker’s groundbreaking sitcom Nathan Barley. Chris’s work has spanned television, film, and music videos for artists such as Holly Johnson and Gracie Petrie, as well as a project commemorating playwright Joe Orton’s Edna Welthorpe letters.

Born in Anfield in 1967, Chris now teaches at Central St Martins in London. I ask him over the phone how he got started in the arts.

“I originally did a foundation year at Liverpool Poly[technic],” Chris says. His accent is the recognisable but soft-edged Scouse of the Liverpool-to-London diaspora. “And I met this great tutor there named Dave Clapham. He’d recently had a one-man show, and he’s about 86 now! And he really encouraged me to apply to a college in the south.”

Chris’s early influences in animation were Monty Python – Terry Gilliam’s surreal cutouts – and Bob Godfrey of Roobarb and Custard fame. His own claymation experiments helped win him a place at an arts college in Farnham.

“I sort of [went] because I’ve always loved films and making films, but I didn’t know the actors. I didn’t have a camera. So what I’d done was started making models from plasticine and animating them.”

That DIY, can-do attitude is an admirable – and often, in a world indifferent or hostile to imaginative pursuits, necessary – trait for an artist of any stripe. Author and filmmaker Clive Barker recently told me how the urge to create admits boundaries of neither genre nor medium.

“I suppose I’ve always been like that,” Chris says. “I remember once someone telling me that they always wanted to be an animator from the offset. Me, I just wanted to tell stories, and I always just wanted to tell them the best way I could. So that’s why I’ve always switched genres.”

Before Anfield Road, Chris had never worked in comics. What was the project’s genesis?

“I’ve done all these different short films,” he says, such as the BAFTA-nominated Dad’s Dead and its sequel Johnno’s Dead, which won best British short film at the London International Animation Festival, “and I wrote [Anfield Road] originally as a script, too.” He talks about how he’d hoped to find financing for a full-length movie. “And then COVID came.”

The pandemic dashed Chris’s hopes for making his feature-film debut. “But then I thought: I could just draw this story. And so I just drew the whole thing.”

It’s difficult to get across what a massive undertaking a project like Anfield Road is. Readers uninitiated in the world of sequential art may have nevertheless heard of Alan Moore, who wrote Watchmen and V for Vendetta, or Jack Kirby, who first designed the dynamic look of characters who are now Hollywood staples such as Iron Man and Thor. Rarer are those polymaths who can both script and draw their comics themselves: the legendary Will Eisner, say, or Frank Miller, of The Dark Knight Returns fame. But even they needed to collaborate with inkers, colourists, and letterers. Remarkably, and befitting his bold approach to getting his work out there, Chris has sole credit for all the artistic facets of Anfield Road.

“I spent four years drawing it,” he says. “I didn’t have a publishing deal or anything – that all came later. I just drew it. Sometimes you’ve gotta do that, haven’t you?”

“Absolutely,” I say, both dumbfounded and involuntarily flashing back to lockdown-era memes about how e.g. Shakespeare wrote King Lear under plague quarantine, and how lazy and unproductive they made me feel. For my own self-worth, I decide to switch the subject of our conversation to his influences.

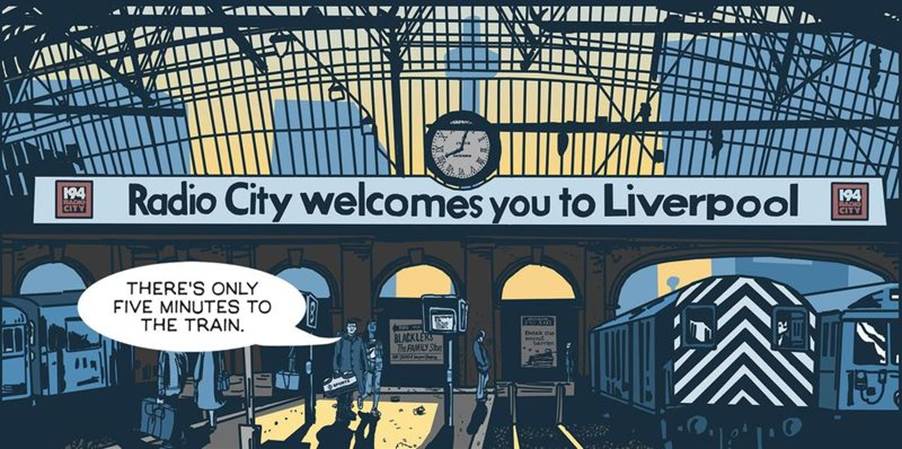

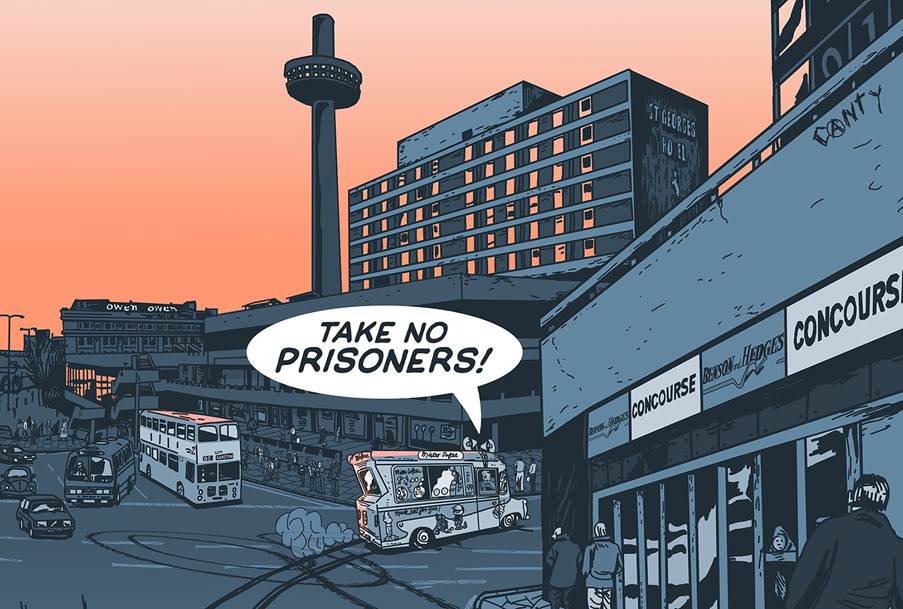

“I’d always loved comic books,” Chris said. “When I was a kid, I never in a million years thought I’d get to do one. Then in the late 90s, I used to go to Paris quite a bit. The graphic novel world is massive in France – ten times bigger than here. And I ended up reading this really great book by Jacques Tardi,” – along with Jean Giraud, Pierre Christin, and my personal favourite, Enki Bilal, one of the giants of the French comics scene – “about a detective called Nestor Burma. And I was really into [the Burma series]. And I thought, if I could have a start, I would really like to be able to draw like him. And that year, in ’98, I did a Christmas card of Santa coming home to Liverpool on the train to Lime Street [in Tardi’s style].” Tardi’s aesthetic in the Nestor Burma series, with its muted-but-solid colours, simple-yet-expressive faces, and complex background renderings of a city in perpetual motion, is a clear influence on Anfield Road.

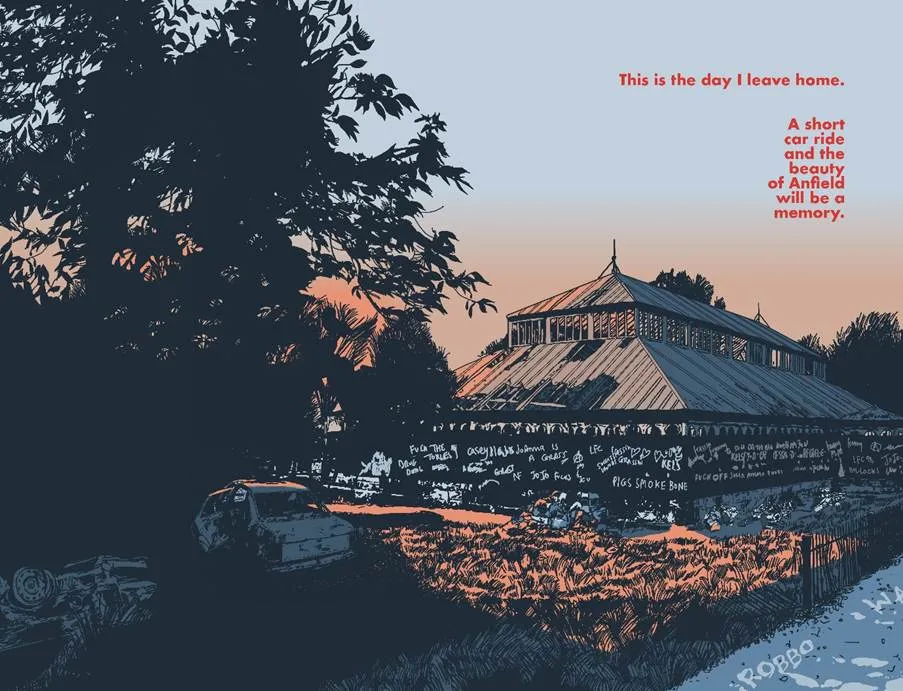

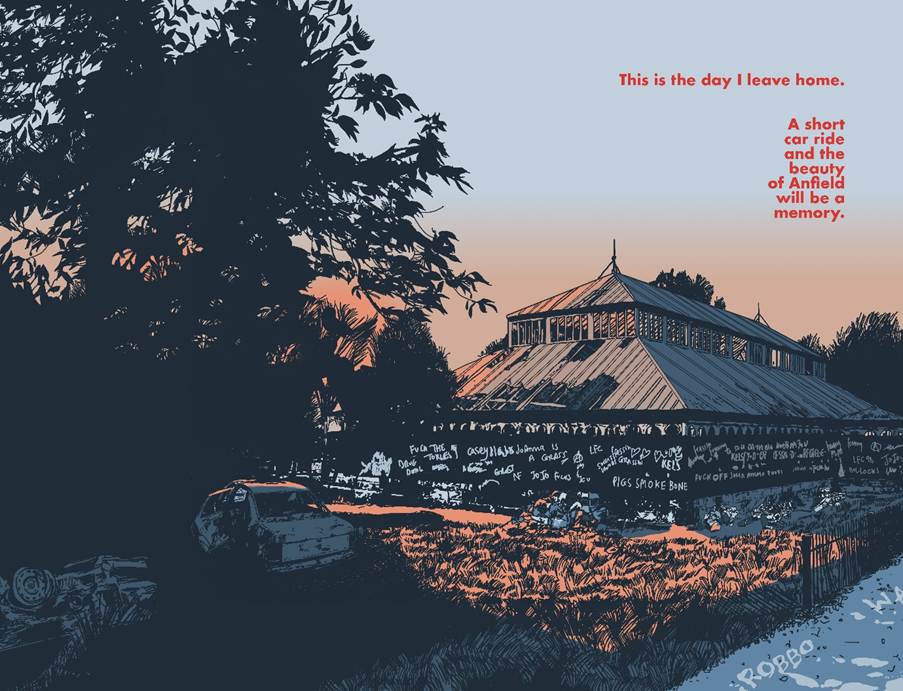

Shepherd’s book is a graphic bildungsroman about Conor, a young lad who lives on Anfield Road with his Gran in the 1980s. He meets Maureen, and dreams of getting out to a London art school. To properly capture the look and feel of Liverpool, Chris utilised old photos, some of which are reprinted in the back of the book. How much of Anfield Road’s story is autobiographical?

“Well, it’s inspired by my youth,” Chris says. “But I mean, with Conor, it is fiction. I like to think – as I say at the beginning of the book – it’s a Northern fantasy. It’s something that never happened… but it’s something that could have happened. I don’t know!”

When a dazzling autodidact jumps head-first into a new medium, a by-product of that idiosyncratic energy can be naïveté. Shepherd’s occasional use of cloudy thought balloons alongside the caption boxes favoured by most serious comics since the 1980s may strike some readers as anachronistic, like if a contemporary film used silent-era intertitles.

At other moments, things that might have been better left implied through visual art are spelled out in awkward exposition. Comic books are, like films, both a literary and a graphic field, and sometimes it’s difficult for the best exponents to find the right balance. Anfield Road manages it for the most part, but not always.

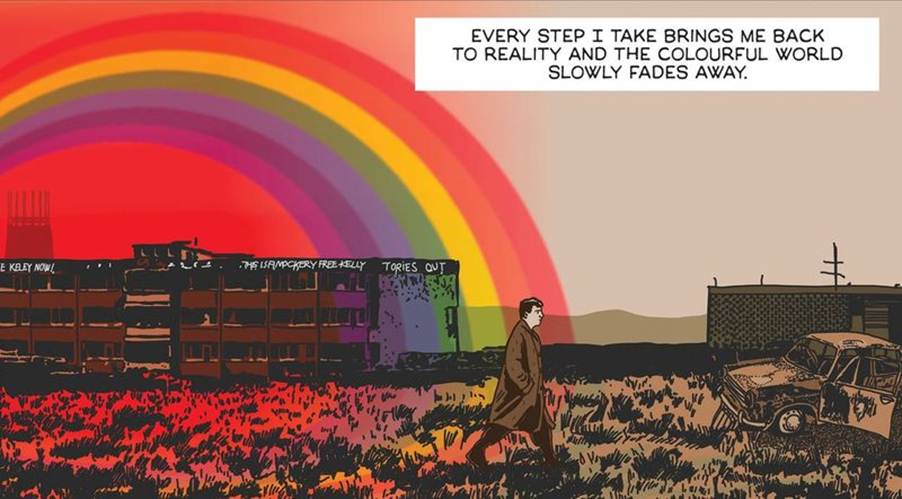

An example: when Conor and Maureen first kiss, the preceding ten pages have depicted a pub scene rendered in a monolithic brown-ale hue. The characters head outside and are met by an equally muted rainy-day blue. But when their lips meet, reds, oranges, greens, and yellows flood the page, and Conor’s drab world is suddenly filled with colour and life. For a moment, love has made the grey rainy day disappear.

“My drab world is suddenly filled with colour and life,” states Conor’s narration. “For a moment, love makes the grey rainy day disappear.” By spelling out a clever visual pun, it’s as though the artist doesn’t entirely trust either his strange new art, or the audience’s ability to understand it.

These days, I encounter much loose talk about how Liverpool should “punch above its weight” — how economic hardship or London-centric indifference shouldn’t prevent us from making great music or art. Shepherd’s approach is an exact antidote to that deprivation and marginalisation, transmuting them into something with great dignity, humour, and flashes of beauty.

“I wanted it to be a bit like when I watch a Shane Meadows film,” Chris tells me. “The way Shane can make a landscape beautiful, whether it’s a council estate or anything else. And I wanted the book to be beautiful, because in my mind, it’s a romance for me: when I see ‘80s Liverpool and everything’s demolished… I have a soft spot for that. Even if, on the face of it, it might be a bit grim, I wanted it to look beautiful. Because it’s the best city in the UK.”

Comments

Latest

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

The Pool of Life

The Shepherd of Anfield Road

‘The sun rises over the dustbins. It's a new day.'