On the front line of Merseyside’s dog attack crisis

Picking up the pieces of our broken canine culture

Mark McDuff still has nightmares about the day he was attacked. It happened with terrifying abruptness as he cycled to work in St Helens. An out-of-control pit bull charged him, knocked him down and started tearing chunks out of him. The owner was nowhere to be seen and it being 6am, nobody else was on the street to help. Mark’s memory of the next five minutes is hazy, but the scars on his arms and legs tell the story for him.

Covered in blood, Mark tumbled into a front garden with the dog’s jaws clamped to his body. His strength was fading as he looked around for a weapon to fight back with, but couldn’t bring himself to hurt his aggressor. “I was screaming for help,” he recalls. “A woman heard me, came to the window and saw me getting attacked.” She rang the police, who arrived just after the owner himself pulled up in his car, in search of his escaped pet. “The owner called the dog’s name and he stopped straight away,” says Mark. “It felt like it was over in a matter of seconds but also, weirdly, like it went on for hours.”

Mark was taken to hospital: he needed one operation on his ankle, another on his arm. The wounds have healed but he still suffers aches and pains. What has not yet recovered, nearly two years on, is his confidence around dogs. “I loved dogs,” he tells The Post. “But I ended up having to get rid of my own dog. I can’t walk past a dog now without crossing the road or having a little anxiety attack.”

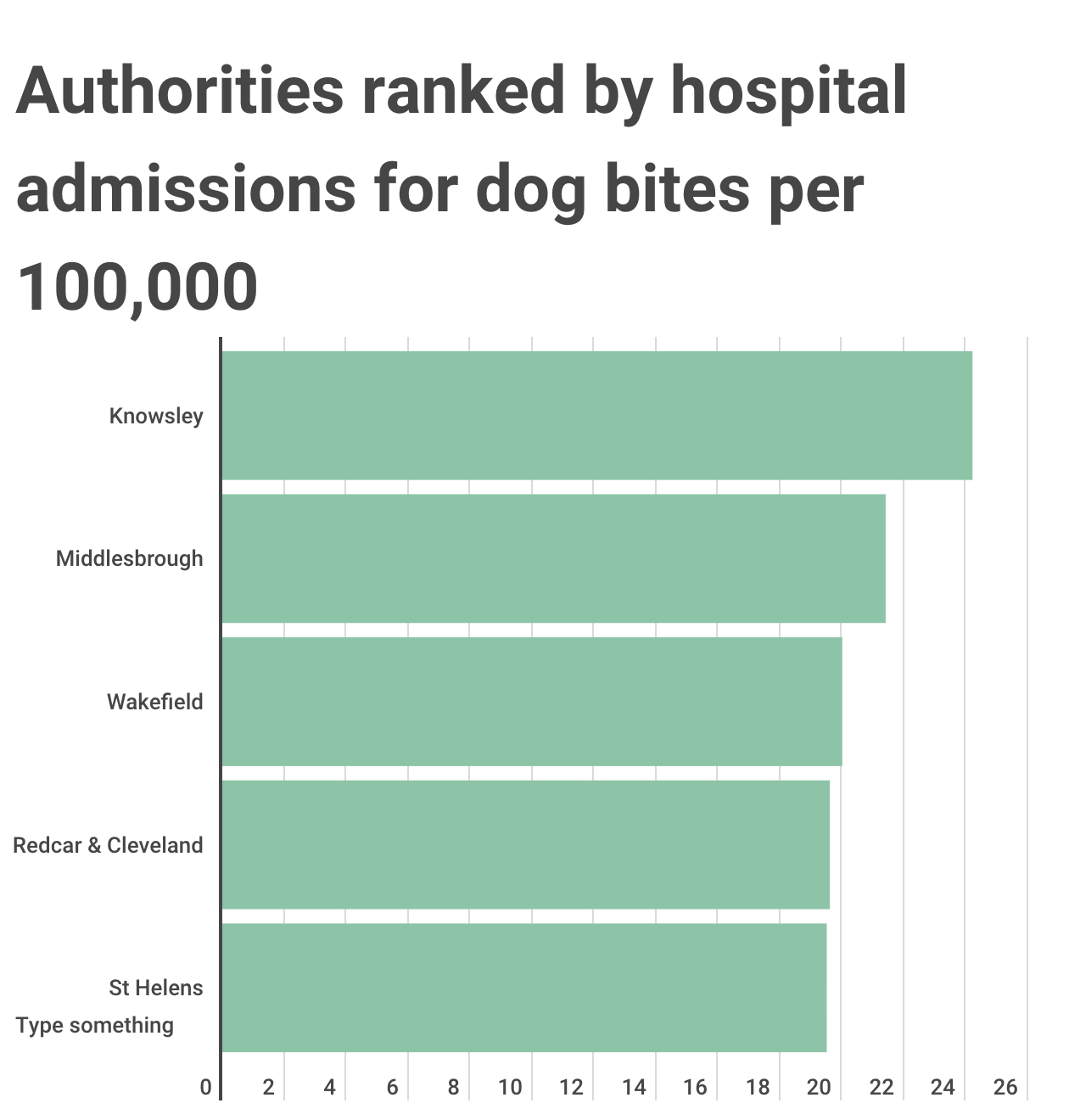

Merseyside bears the grim distinction of being one of the worst regions in the country for getting mauled by a dog. Last year, the NHS ranked the local authorities with the highest annual dog bite admissions: among the top five, Knowsley is first and St Helens is fifth (Middlesborough, Wakefield, and Redcar & Cleveland come second, third, and fourth). By way of comparison, hospital admissions are ten times higher in Knowsley and St Helens than the least affected areas of North London and the Isle of Wight. In addition, every day, a child is treated in the Alder Hey for a dog attack, according to Dr Christian Duncan, a plastic surgeon at the hospital.

The rate of Knowsley’s hospital admissions (24.2 per 100,000) is ten times higher than Harrow (2.4), Brent (2.7) and the Isle of Wight (3.1)

Two high profile cases in Merseyside last year brought this crisis into sharp relief. In October 2022, a 65-year-old woman named Ann Dunn was killed in a dog attack at her home in Vauxhall (80% of attacks occur at home). In March, Bella-Rae Birch, a 17-month-old child, died after her family’s pet dog mauled her to death at home in St Helens. Both tragedies have prompted a great deal of discussion around what makes Merseyside unique when it comes to violent canine incidents. Is it the popularity of so-called dangerous breeds of dog? Is it irresponsible ownership? Is the impact of Covid lockdowns important?

The Post has been trying to find out why dog attacks are rising, and nowhere is the extent of the problem clearer than at Birkenhead Kennels. Based on an industrial estate close to the Stena port, these kennels take in dogs abandoned by their owners for being uncontrollable and potentially dangerous. Sam Simpson, who manages the kennels, shows us around, along with her colleague Cheryl Smith. They are a no-nonsense duo, doing the best they can with a meagre budget for the most unloved dogs in the city. Sam sees her role as “picking up the pieces” of Merseyside’s broken dog culture.

The dogs are housed in a building next to the office. Sam clanks open the front door lock, at which point a discordant canine orchestra strikes up, and we walk inside, shouting over the hullabaloo of barks, howls, and whines. The concrete walkway is flanked by metal cages and like Clarice Starling in Silence of the Lambs, we peer into each one while nervously advancing. This scene is much sadder than the one in the film. Dogs get up onto their hind legs and press their snouts through the wire mesh to sniff and lick our hands and whimper when we leave them.

Cheryl says big dogs are less likely to be rehomed than wee ones, which typically stay only for a few days before someone takes them in –– families with small children prefer teacup pugs to man-sized hounds. This means larger dogs can be stuck in the kennels for months, and can end up going “kennel crazy”, an irreversible state that Cheryl describes as especially aggressive, territorial and misanthropic –– when visitors come, a kennel crazy dog will size up them up for attack instead of affection. If a big dog has been locked away for a long time without anyone wanting to rehome it, and has been deemed kennel crazy, there is only one option left. The dog will get put down.

We meet an American XL bully that weighs 50kg (they can go up to 60kg), as well as a malamute (bred to haul heavy freight as a sledding dog), and large terrier crosses. “We get up to 15 calls a day asking for dogs to be picked up,” says Sam. “That is the reality we’re in. We get calls from people who say their dog has gone for their husbands, gone for them, gone for their kids, and can we take it in? But how can we rehome dogs to new families and say this one has gone for its previous owners?” As unpleasant as it sounds, the kennels advise putting dogs to sleep if they have bitten humans.

We walk back into the office — a tumbledown room with a computer and a few chairs — where Cheryl says the majority of their calls now concern XL bullies who are bred for their strength and size and purchased by owners unable to control them. There is nothing inherently unmanageable about XL bullies, she says, but they need to be assiduously trained and handled. “Any dog that feels threatened enough will bite,” she explains, “but it’s the sheer power of a big dog that is a concern. A chihuahua can snap, but it’s not going to bite off your hand, rip off your face, or even worse, kill you.” As if to illustrate the size divide, a little bulldog named Spud pootles in. He sniffs my hand then bustles into the next room, where we hear a groan. A kennel worker reports that Spud has peed on the floor.

So to get back to the rise in dog attacks –– what do Sam and Cheryl think is behind it? First, Merseyside apparently has a taste for “status dogs”, large, strong breeds that can grow to sizes comparable to humans. A status dog, like a Rottweiler or a Staffy, is meant to burnish a tough guy’s image. But women also get them for safety and families choose them as exotic pets, like they were designer goods.

A second factor, according to Sam and Cheryl, is a drop in training. This is hard to quantify, and kennels, of course, would expect to deal with pets that have had a difficult life, but the Birkenhead team say they increasingly come into contact with dogs that haven’t even been taught how to sit. Cheryl says owners can be incredibly naive when it comes to training. “They usually get the dog as a puppy when it’s really young,” she explains. “They do no research and give it no training, then the puppy gets really big and powerful and headstrong, as with most status dogs. They can’t control them, which is when they phone us up asking for help or to take it in.”

Once a family realises their dog is uncontrollable, they might pass it onto another household, which gives it to someone else, and the cycle continues, confusing the animal with every new home. “By the time it comes to us,” Cheryl says, “it’s so disoriented and untrained there’s nothing we can do. It doesn’t know what’s expected of it. They’re fully grown, massive, and there’s not much you can do to control a dog like that.”

A third element might be the impact of lockdowns, when dog ownership surged. Cheryl says that many puppies purchased during this period were not socialised around other dogs and humans, and now that they are adults, there is a lost generation of maladjusted pooches. Many owners are back at work so their pets are also under-exercised, frustrated, and buzzing with pent-up energy. Hospitalisations due to dog attacks were already rising before the pandemic (in 2002, 3,400 people were admitted nationally for this reason –– in 2018, that number tripled to 8,400). But most canine experts say the lockdown years have accelerated the trend.

Is there a fourth component to this crisis? John Tulloch, a vet at the University of Liverpool (who did not respond to an interview request), has warned of the dangers of pet trends online. “I do think the way you see people interacting with dogs on social media is very different to what was occurring, say, 20 or 30 years ago,” he told the Guardian, describing how popular videos that show dogs baring their teeth may suggest animals are smiling, when in fact they might be stressed and getting ready to snap. Anthropomorphising pets is clearly nothing new –– the Victorians were fond of dressing dogs up in fancy dress shows, as you can see from these bonkers pictures –– but perhaps TikTok trends are giving some owners bad ideas.

In any case, Sam and Cheryl believe that something has gone deeply wrong with local dog owning habits. They habitually meet liars who come in to abandon their dogs, claiming to have found them by the side of the road. The Birkenhead Kennels team are canine detectives, and can usually tell if something is amiss: the dog might still have a matching collar and lead, or try to follow the Good Samaritan out the door –– signs that it is not a stray. Sometimes Sam and Cheryl will scour social media for pictures of the “stray” dog and identify their former owners –– but in that instance, they do not have the authority to reunite them. “If they don’t want their dog back, once it’s here there’s nothing we can do,” says Sam. How do they stay upbeat? “It’s hard. But it’s part of the job.”

The RSPCA has called for the reintroduction of dog licences as a way to ensure animals go to responsible owners. However, as Dr Tulloch has pointed out in a previous interview, licences have not proved effective in other countries at reducing attacks. One option put forward by experts is tying a dog licence to a training course, as Germany does, but there it is not mandatory and thus hard to enforce. A recent academic paper concludes that education is probably not enough to stop dog bites, and that the issue should be tackled earlier when it comes to breeding, especially when considering the temperament of the dog’s parents.

Both Sam and Cheryl say that improving the rate of dog attacks rests with owners researching breeds, especially if they are large, plus spending the time to train them properly. There have separately been calls to expand the list of banned dog breeds (which currently includes Japanese tosas, dogo Argentinos, fila Brasileiros, and pit bulls), although some experts believe that nurture far outweighs the importance of nature. That’s also what Mark thinks. “There’s not a lot of dangerous dogs,” he says. “I think it’s silly owners who don’t know what they’re doing.” The animal that attacked him was a banned type of pit bull, although the two fatal incidents mentioned earlier involved legal breeds of dog.

A miserable thought occurs to us as we leave Birkenhead Kennels: this crisis has been engineered by humans who have bred these dogs to be large and forceful, abandoning them when they become too much hassle. Ignorance doesn’t just physically harm human victims but condemns dogs to a frightening end in a kennel cage and the risk of a fatal injection because their owner once thought they would be a cool accessory.

Today, Mark works as a chef at a restaurant in St Helens, although he had to leave the job he had when he was attacked. He has mixed feelings about the fate of the dog that attacked him, which was put down. “That was the last thing I wanted,” says Mark, “but if it didn’t happen to me, it could have happened to a child or pensioner”. Last January, the pit bull’s owner pleaded guilty to being in charge of a dog dangerously out of control, causing injury and possessing a banned fighting dog, and was sentenced to 28 months in prison. He is believed to have since been released. Mark bears the owner, Shaun Dwyer, no ill will. “I don’t want to say bad words about him because he saved my life that day,” he says, magnanimously. “But it is worrying that people out there own dogs capable of this.”

Comments

Latest

The unexpected auction: A London fund manager is selling Merseyside homes from under their tenants

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still plays every Saturday

On the front line of Merseyside’s dog attack crisis

Picking up the pieces of our broken canine culture