Merseyside’s missing babies

Gina Jacobs’ son was buried in a mass grave in 1969. Now, she’s helping other families find their baby’s resting place

When Gina Jacobs and her ex-husband Jimmy learned they were expecting their third child late in 1968, they were overjoyed. Both 24 years old at the time, they’d met at a youth club in Birkenhead nearly a decade earlier, when they were teenagers. Having a big family had always been their dream. With a four and two-year-old already toddling around their flat in Victoria Port, they were excited to have another baby to coo over.

Like both her others, it was an easy pregnancy. Gina loved nothing more than watching her belly grow. She got the new nursery prepared with tiny clothes, a wooden cot, toys and nappies.

Shortly before her due date in February 1969, she went into labour. “I was so pleased, because this one baby was coming early,” she remembers. All of the other mothers at her children’s school, Cathcart Primary, had been equally excited to find out what she was having. “Put a blue blanket in your window if it’s a boy, and a pink one if it’s a girl,” one of them told her before she made her way to St Catherine’s Hospital.

But as soon as she gave birth to her baby, she knew something was wrong. She watched as the faces of the midwives around her changed. Gone were the happy expressions, replaced by ones of discomfort and sadness. “I just remember the silence after [the baby] was born,” she tells me. “That terrible, terrible silence.”

Gina was told her baby — a son she named Robert — was stillborn, and within seconds his tiny body was wrapped up and taken out of the room to be prepared for burial. She wasn’t given a chance to see his face, or to hold him. As she recovered from the birth, she was placed on a maternity ward, surrounded by other mothers with their newborns. “I just couldn’t stop crying,” she says. “I remember one girl asking if my baby was on the premature ward, and I tried to explain to her, but I could feel her drawing away.”

Gina is one of thousands of women across Merseyside and around the country whose babies were stillborn before the mid-80s, when they were robbed of an opportunity to see their child or say goodbye. Since hospitals and maternity wards took responsibility for organising stillborns’ burials, parents often didn’t know what happened to their baby after they were taken away. Some weren’t even told their baby’s gender.

After Robert’s birth, Gina and Jimmy were assured that their child would be buried later that day, alongside a “kind” woman who had died recently. It would be many years later when they finally found out the truth: Robert was buried in a 10-foot mass grave at Landican Cemetery with over 60 other stillborn babies.

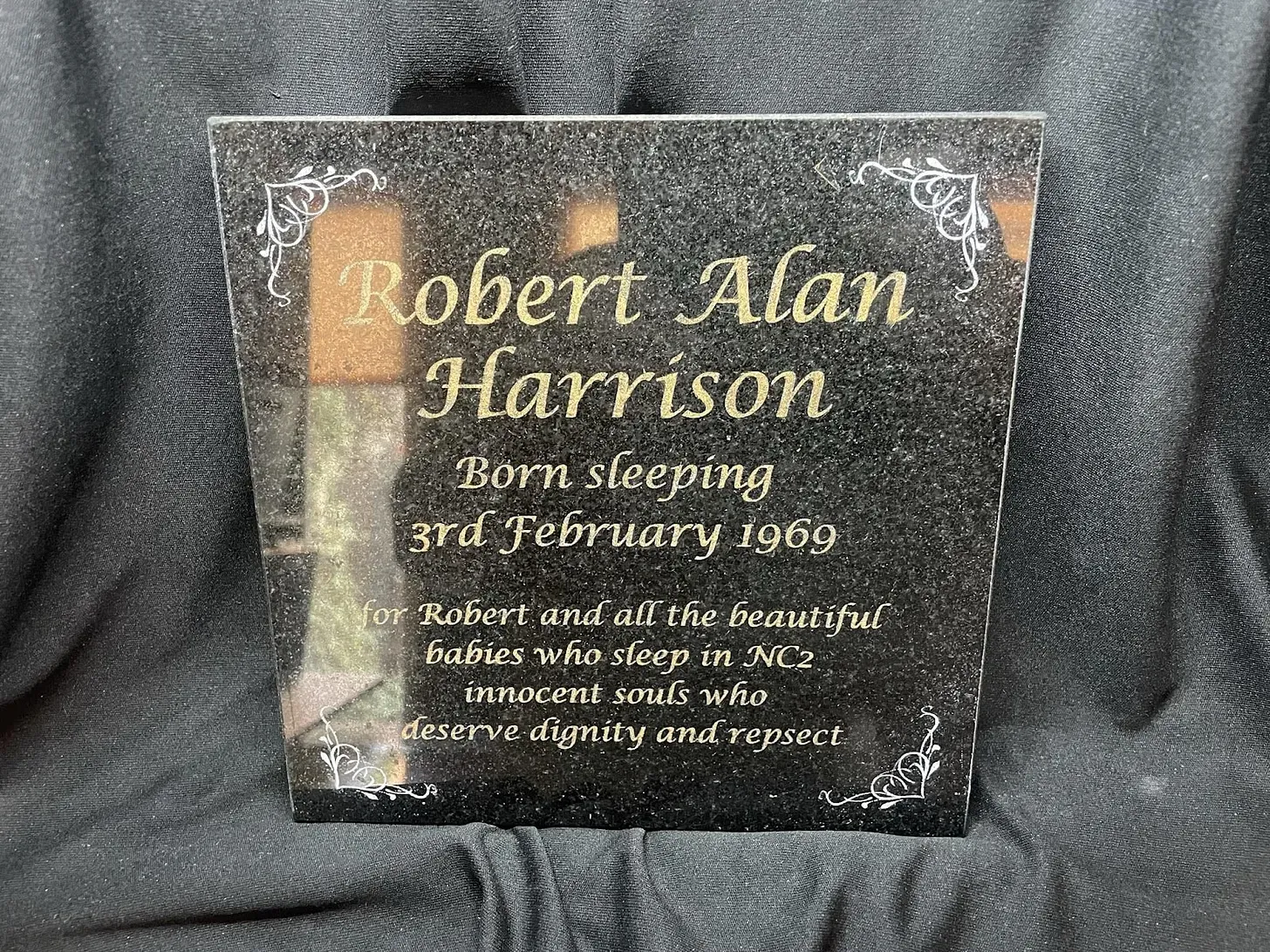

“I mean a little hamster, quite rightly so, an emotional family pet, would have been treated with more respect and dignity,” Gina says. “It was heart-breaking.”

Questions around why hospitals and local authorities misled families around their child’s burial linger to this day. Since 2022, numerous documentaries have aired about the scandal — including a BBC documentary called The Missing Babies from earlier this year — spurring former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to address the topic in Parliament, though he stopped short of apologising for the government’s directive around stillbirths at that time.

Yet this national recognition has been little consolation for the families still searching for answers. Due to poorly kept or missing burial records, the vast majority of people seeking their stillborn babies’ resting places have found it nearly impossible to locate the grave — or even the cemetery — they were buried in.

That’s why, since finding her son, Gina had embarked on a crusade to reunite families with their stillborn children. In late 2022, she set up a Facebook group called Gina’s Sleeping Babies Reunited to share information and support, which now has over 400 members. “Nationwide people are speaking to me [on Facebook], and we all have the same story,” Gina says. “And this tells me that this was a directive that was put out to people all over this country.” As time goes on, she’s become “more and more angry” over local authorities’ decisions to mislead families for so many years as to the fate of their stillborn babies – and she wants the government to explain themselves and apologise.

One of the women Gina is currently helping is Lin Bruchez. She gave birth to a baby in Whiston Hospital in Knowsley in 1975, and over the past few years, she has been searching for the resting place of her stillborn.

At 26 weeks pregnant, Lin was told by her doctor that she’d lost her baby. Shortly afterwards she gave birth, and just like Gina, she wasn’t given an opportunity to see or hold her child. She wasn’t even told the gender. “The midwife covered the baby over with a white sheet and pushed my Mum's face away and said, ‘Don't look’,” Lin’s daughter Jo explains. She was told about the stillbirth from a young age, and has been helping her parents find out exactly what happened to her sibling.

At the time, Lin and Eddie were both told their baby’s burial would be organised by the hospital, with no detail offered as to where they would be laid to rest. Months later, when they enquired about what had happened to their child, they were told a fire in the hospital had destroyed most of their medical records.

It wasn’t until Jo was born two years later that the family were made aware of the details of the birth, and that their baby had been a boy. “They took me to get me registered, and they started quizzing my mom asking why she hadn’t registered her son,” Jo says. The staffer at the registry office had seen Lin’s medical records and hadn’t realised the son in question had been stillborn, and was inquiring as to why there was no birth certificate.

After this, Lin began suffering severe emotional distress. “Mum just wasn’t well at all after having me,” Jo says. “Obviously she hadn’t dealt with losing him, so she really struggled.”

For many families who suffered a stillbirth prior to the mid-80s, it’s the way they were treated in the aftermath of such a traumatic event that sticks with them. Nowadays, families are given a chance to hold their stillborn babies, to name them, to take photographs, and to plan their funerals, as well as join support groups for other grief-stricken parents – instead of being told to immediately “forget and move on”. But back then, Gina recalls, it was “such a lonely journey because there was absolutely nobody there for you”. When she returned home from giving birth to her son, she was visited by a midwife. “She came in with this little box with welcome things in it, and she said ‘Congratulations!’. I had to explain to her, nobody had told her I’d lost my baby. I just remember thinking that’s how irrelevant we were.”

In the months that followed, Gina struggled immensely with her grief. She already had two children, Karen and David, and explaining to them why she couldn’t bring a little sister or a brother home from the hospital was near-on impossible. Shortly after the birth, she remembers overhearing a conversation between them. “[Karen] told David she wished the baby hadn’t died,” she says. “She was only five. Imagine wishing for a baby not to die at that age.”

Her husband Jimmy was also deeply affected by the loss of their child. “He had a personality change afterwards, it was horrendous,” she says. “I wouldn’t have 1969 back if it was offered to me on my death bed.”

Like all of the fathers of stillborn children at that time, Jimmy was responsible for delivering Robert’s body to the graveyard for burial. The day after the birth, he picked up his son’s remains from the hospital in an unpadded cardboard box, and since he didn’t have a car, he carried them to the cemetery on the bus, holding the box on his lap. “I realise the trauma that he must have had holding and carrying that box,” Gina remembers now. “We never really spoke about it, and I kind of blamed him for not asking more questions as to where Robert was buried.”

For many years, Gina and her family had no idea what had really happened to Robert’s body. It wasn’t until they watched a BBC news item in 2022 revealing that stillborn babies across the North West were frequently laid to rest in mass graves that they realised what had happened. In that news segment, a woman named Lilian Thorpe stood over her stillborn son’s grave, where he was buried with eight other babies. “Mummy’s here,” she said, touching the ground.

After watching the news, Gina — then 77 years old — was driven to find out what had really happened to her son Robert. “I just found it so hard to understand,” she tells me. “Every time a baby was left at a cemetery, that lie was told over and over again…I can’t tell you how angry I feel.”

After searching through archives and contacting Landican Cemetery, she was eventually able to locate his exact burial location in the summer of 2022 — a mass grave with over 60 other babies that she now visits now on a weekly basis to lay flowers. “If we were told this in the first place, we could have been visiting all these years,” she says. She and Jimmy hadn’t tried looking for their son earlier because they’d been told he was buried with a woman. ”What if the family was there?” Gina remembers thinking. “You felt you were infringing on someone else’s family grave.”

After 18 years of marriage and three children, childhood sweethearts Jimmy and Gina eventually divorced. In part, Gina attributes the separation to the way in which they lost Robert. “We'd never dealt with anything like it, like loss and death,” she says, “and [Jimmy] wasn’t the same afterwards.”

Indeed, it seems that after any great loss like this, it is hard to fully recover. I speak to another woman, Bernie Stanton, who has been searching for the resting place of her older sister, who was stillborn in 1958. Her parents, both Irish, who relocated to Liverpool in the 1940s, never spoke about the death of their first born, but it was clear it affected them deeply.

Bernie explains that when her mother was pregnant with her, she refused to buy anything until she was born: not cot, no clothes, no toys. It was the same when Bernie had her own children, too. “I could buy a few vests for the child, but I couldn't buy any pram or anything like that,” she explains — her mother wouldn’t allow it, just in case the unthinkable happened again.

After watching The Missing Babies on the BBC earlier this year, Bernie was shocked to realise her older sister may have been buried in a mass grave. She decided it was time to track her down. While both her parents died in 1999, she was keen to reunite them with their lost child.

Now living in Ireland, she contacted a friend in Liverpool to assist her, and within a matter of weeks she was put in touch with Gina.

In addition to helping other families locate their missing babies, Gina has also been campaigning for the government and local authorities to apologise for their role. However, the biggest change she wants to see is to the stillborn register. Back when Gina had her son, babies on the stillborn register were not named in their listing, so she is campaigning for an amendment that would allow children’s names to be added posthumously. As Gina is keen to stress during our conversation: “What kind of person doesn’t allow a child to have a name?”

We contacted Southport’s Registry Office about making this change, but they did not respond to our query. A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care said its “sympathies are with Gina and all the women and families affected”, and that they expect hospitals to provide “as much information as they have available to any parents who inquire about what happened to their stillborn babies”. They explained that all parents are also now able to apply for baby loss certificates, “regardless of when the loss took place.”

In 2023, Wirral Council installed a memorial plaque in Landican Cemetery — where over 1,000 stillborn babies are now thought to have been buried — and last year the council’s chairperson Ian Lewis apologised on behalf of the local authority as well as the previous councils. “With the benefit of hindsight, it should never have happened,” he said at a meeting last month. “Decisions were taken at the time that today would be wholly unacceptable.”

Since that meeting, councillors have agreed to write to the government and Wirral’s four MPs “to request attention to this issue and look at a national scheme to end this outrage across the country.” Liverpool City Council has taken a similar approach, telling The Post they are helping “many families to trace the graves of their children and place a small memorial if they wish”. “We work closely with the Liverpool Women’s Hospital and other NHS bereavement teams to ensure that parents who have lost children during pregnancy or under 18 years of age have choice and financial support when organising the funeral,” a spokesperson said. “We fully understand the grief and anguish of parents affected by historic practices.”

“There are just so many parents that have gone through this, and there really is a lasting grief and a lasting resolve to find where the babies are,” Kris Brown tells me. He’s a councillor in Woolton and Gatacre, and has been working alongside Gina and numerous other families to help find their stillborns over the past few months.

He says that it has been “a struggle” trying to piece information together, with certificates that are supposed to be issued when a baby is stillborn and records of burial often “non-existent”. “It’s like some of these babies didn’t exist, full stop," he says, “and there seems to be a lot of misinformation, or just a lack of information, that varies from area to area.”

With the help of councillor Kris Brown and Gina’s Sleeping Babies Reunited, Bernie has been able to locate her sister’s grave in Liverpool. She’s planning to fly over in the next month to lay flowers and collect soil from the grave to take back to her parents’ resting place in Ireland.

But many other families are still in the dark. Lin and Eddie, now both 78 years old, remain desperate to locate their son, and while Jo maintains she will continue looking for his burial records, she admits “we are no closer to finding him”.

“I'm trying to be positive for [Mum and Dad],” she says, “but what hurts the most is when my Dad says to me: ‘I need to find him before it's too late’.”

Gina intimately recognises the family’s pain. “I can put myself in their position,” she says. “If I had not found Robert that day, and there was no record of him, I'd be thinking, Well, where is he? What did they do with him?”

Now 80 years old, she tells me she won’t stop until every family is able to reunite with their stillborn. “I will fight until my dying breath for these babies.”

Have any information that could help reconnect a family with their lost child? Please email abi@livpost.co.uk.

Comments

Latest

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Merseyside’s missing babies

Gina Jacobs’ son was buried in a mass grave in 1969. Now, she’s helping other families find their baby’s resting place