Life on Lark Lane

From a box of photos and records in California, an academic traces the history of a vibrant Liverpool street

In the late 1970s, Kay Flavell moved into a red brick terraced house on Pelham Grove, a small avenue off Lark Lane. She had just come from the Wirral, where she lived with her husband and had given birth to her daughter, and had spent some time living there while commuting to London, where she taught eighteenth century German literature at UCL. Her discipline was exciting — but the problem was, she loved talking to people. And when you’re studying the eighteenth century, they’re all dead.

Lark Lane had an intrigue to it. She would go out wearing her red beret and notice musicians practising for gigs in the park. Mothers would confidently leave babies in prams outside the shops. The launderettes were filled with chatter. There was a faded beauty to the grand houses — a loss of shipping and mercantile wealth, and the effects of post-industrialisation and the new Thatcher government were being felt. Yet still, the Lane felt diverse and abundant — a transient young population brought in new life and music, a new wine bar was opening and the antique and book shops maintained a quiet presence.

There was a common saying “You can get everything you need on the Lane”; they had butchers, bakers, groceries, doctors, and dentists. On the weekends, there were “Larks in the Park” — parties in the Victorian bandstand at Sefton Park, which gave brief cult status to the struggling psychedelic and post-punk bands of the era. “I thought oh my god, this area is changing so much,” Kay says. “It would be so good if I could record this moment happening right now.” She deliberated for a while — she was in the middle of a one-year sabbatical researching the life of George Grosz, a Dada artist who escaped from Nazi Germany, and taking on another project would involve a lot more work. But she was sure there was an importance to where she was, and Liverpool was beginning to fascinate and move her.

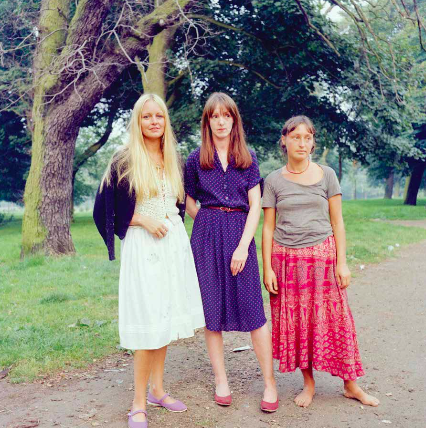

At one point it was decided: she was going to write about Lark Lane. She commissioned Tom Wood, an artist from Ireland who was beginning to make a name for himself as a talented portrait photographer, to work alongside her conducting interviews and taking photos. What evolved was a series of interviews with the residents of the lane, painstakingly transcribed and condensed for clarity, alongside close and colourful portraits of their subjects.

“I always felt Lark Lane was a really special place,” Tom Wood tells me. He ventured out every day with a Rolleicord, a film camera using high exposure, to hang around with artists and musicians, people in the park, and students on street corners. “People of the Lane was one of the nicest things I ever did. It was really personal.”

A year went by and Kay’s sabbatical came to an end. She was drawn back to the US to file her George Grosz biography. Other research projects came up — a study into the Scandinavian migration to New Zealand, an urban planning project looking at the post-industrial waterfronts of Vallejo, California. In between this, she spent the 1980s carefully transcribing the interviews, and kept them in a box in her home. But at some point, she finished the transcriptions, and put them to one side. Something held her back, other projects stood in the way, and she didn’t look back.

In 2019, Kay was visiting Liverpool to research the regeneration of post-industrial waterfronts. She made a short trip to Lark Lane to visit friends. She showed them the manuscripts and photos. They urged her to publish it.

Forty years had passed. She put out a tentative post in a Facebook group named “People from around Lark Lane” asking if people would like to be involved. The messages came flooding in. There was an overwhelming enthusiasm to see the old interviews, and share new ones. People even suggested their families had been involved — could they read what they said?

This time, Kay wanted to use modern recollections lifted from social media to illuminate how things had changed. Social media was a saving grace in this respect — the pandemic was beginning and human interaction was scaled back to a minimum. But a wealth of connections made through the Lark Lane Facebook group enabled her to add a new dimension to the book.

This time, Kay was interested in drawing out key themes. She reels some of them off: childhood, families, school, first jobs, memories, food, games, healthy and sick. “I’m so glad I included that one because of the stories about the doctor, they’re hysterically funny. Really wicked.” What she’s thinking about comes from a local man called Graeme Edwards, who contacted her to be involved in the project. He told her: “Dr Macken’s was at the corner of Little Parkfield and Lark Lane. The waiting room was always full of smoke, as was his surgery.” Elaine Dutton also chipped in, “As well as getting you better, Dr Macken would offer patients a cig if they went to him with a problem and needed to talk. He was also known to give out tips for horses. If you were really ill, it was best to go to morning surgery, as he had had a good drink by the evening surgery. Great doc, lived on the Lane, a man of the people.”

One comment on the Facebook post was particularly striking. It came from a woman named Helena Paxton, who wrote about her childhood growing up in Portugal and returning to Lark Lane when she was young; how she could still remember the smell of fresh bread at the bakery, and the way her Liverpudlian grandmother attentively tended to her garden. “I thought god, she can write,” Kay says. “And it turns out she can edit, too.”

Helena took on an editing role — she was happily retired, and devoted to the idea of honouring her hometown. People of the Lane also had personal resonance — through collating the interviews, she was reunited with cousins and uncles she’d lost contact with years ago. Kay was working remotely, self-isolating in her farmhouse in Vallejo, California, and what Helena offered was a closeness and a fine-tuning that enabled the book to become much warmer and more human.

It wasn’t always a simple project and when published, it touched a few nerves — including a relative of the heavy-drinking, heavy-smoking doctor. His daughter came on the website and claimed it was wrong — he didn’t smoke, nor did he drink on the job. Kay asked Elaine if she could still quote it, who agreed. “So the daughter trying to censor it, that really wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted to give it truth. And I think there is a truthfulness here,” Kay says, clasping the book in her hands.

The other challenge was giving it balance. Reading back over an old interview with a local resident, Mrs Jessie de Larrinaga, who claimed to be from an old Liverpool Hispanic shipping family, Kay noticed a deep disdain for other residents: “I think the area has gone down terribly. You can’t even get the sidewalks repaired. There are potholes everywhere. I don’t think we’ll hang on for more than a couple of years. Housing associations spend a lot of money on the property, but then they often put the wrong type in. I don’t know anybody around here now.”

“We always think about things in moral terms, don’t we?” Fay says. “Say you’re trying to be kind, or not unkind. I wanted to recreate some of the dialogue.” Geoff Edwards, who used to deliver the papers to the de Larrinagas on Livingston Drive, remembers also delivering the family's “monogrammed cigarettes” to the housekeeper. He added that when the eccentric Mrs Jessie de Larrinaga would take her dog for a walk Jessie would follow it in a car.

On the whole, the book is fair and empathetic to the people within it. It expresses a deep fondness and nostalgia for Lark Lane and lifts the voices of the people who lived there and loved it. It may be a document of the lives of ordinary people, but there is a unique historical value to their feelings and thoughts at a time of great social change. Looking back, what you mostly find is joy.

We’re talking in Keith’s Wine Bar, the very same that opened all those years ago. Parisian jazz is playing in the background. Outside there’s rain on the windows. People filter in and search for Kay — they spot her beret, and sit down with her, and she signs their copy. I wonder if she feels a bond with this community now — would she say she’s a Lark Laner? She shakes her head, pen poised in her hand. “I’m just the outsider who comes in and sees that if you work together, these places can be amazing.”

You can find all these memories and more of Tom Wood’s photography in People of the Lane. It’s available to buy from News from Nowhere on Bold Street, and most bars and shops on Lark Lane. To order a copy online, just email hpax31@gmail.com.

Comments

Latest

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

Life on Lark Lane

From a box of photos and records in California, an academic traces the history of a vibrant Liverpool street