Mersey Beat: Jack Kerouac's epiphany in the Liverpool docks

Plus, the latest Covid-19 data for the Liverpool City Region, and our Post Picks

Good morning — today’s newsletter has the latest Covid-19 data in the city region, a few recommendations of how to fill your time in the remainder of the lockdown, and a lovely piece by our writer David Barnett about Jack Kerouac’s trip to Liverpool as a sailor during the Second World War.

If you think a friend or colleague might enjoy this newsletter, please do forward it to them, or you can use the button below to share it on social media or via text or group chat.

Mini-briefing: The latest Covid-19 data

Vaccination: More than half a million people in the Liverpool City Region have now been vaccinated, according to figures released by mayor Steve Rotheram last week. 45.2% of people over 18 have received their first dose, and 88.8% of over-60s. That data was up to March 7th, so the numbers will now be higher. More details here.

Cases: The rate of new cases is now lower than the national average in both Liverpool and across the city-region. The LCR case rate (number of new confirmed cases in the past week per 100,000 residents) is 52.6, down 10.5% on the week before, and the Liverpool city rate is 53, down 4.7% in a week. England’s rate is 58, down 2.9%. See our dashboard below for more details and if you want to follow the dashboard live as it updates every day, click here.

Useful context: Health experts have warned that the very rapid declines in rates that we’ve seen in the past month will slow down and could go into reverse because of the vast testing happening in schools. The more testing you do, the more cases you pick up, so that might explain the flattening you see on the right-hand side of the graph below.

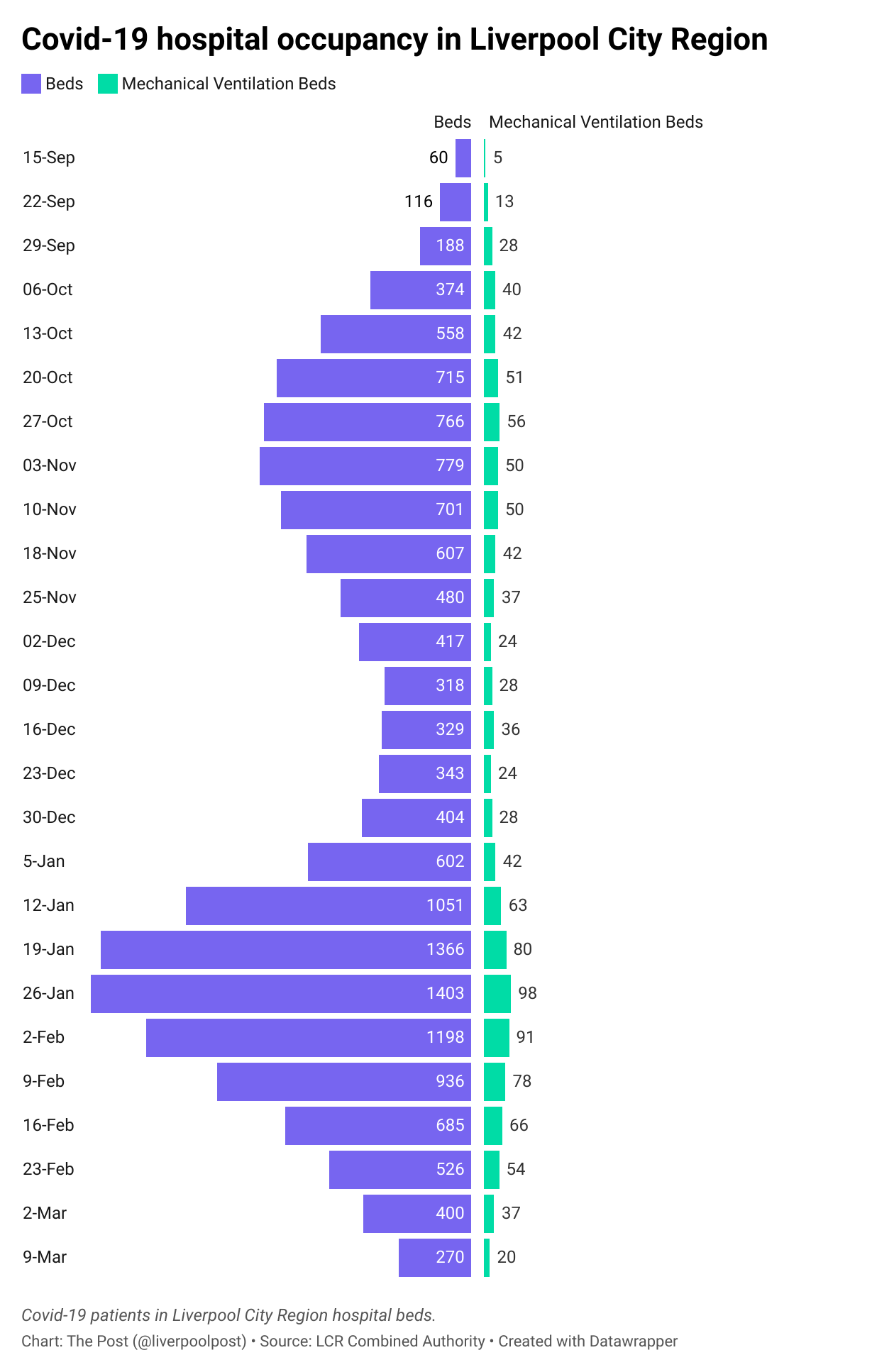

Hospitals: In late January there were 1,403 Covid-19 patients in our hospitals (in the city region, that is), and 98 whose condition was so serious they were on mechanical ventilators. The most recent figures show a fraction of those numbers: 270 patients and 20 on ventilators. See the hospitals graph below for more details.

Worth watching: If case rates do begin to tick up in the weeks ahead or plateau at the current level, it will be well worth watching the hospital numbers. Widespread vaccination should mean new cases don’t translate into hospital admissions at anywhere near the level they were in January.

Post Picks: Our recommendations

Worth a watch: Next Thursday, join Sefton Borough of Culture and The Reader for an evening with Max Porter, author of Grief is the Thing with Feathers, Lanny and most recently The Death Of Francis Bacon. Porter has been described as “one of the rising stars of British literature.” Book your tickets here.

Worth a listen: When Boris Johnson won the 2019 election, he pledged to ‘level up’ the UK. Many doubt whether he meant it and others wonder if it’s even possible in the wake of the pandemic. FT journalist Sebastian Payne takes a road trip from Sedgefield and Liverpool to Stoke-on-Trent to find out. Listen on BBC Radio 4. You can also read Payne’s piece in the FT about the same topic here.

Worth a look: The UK’s largest festival of contemporary art is back. The Liverpool Biennial 2021 will take place across various locations in Liverpool, including Bluecoat, Liverpool Central Library and Cotton Exchange Building. The preview takes place today.

More info: This year’s edition The Stomach and the Port looks at ways of connecting the world. It is described as “A dynamic programme of free exhibitions, performances, screenings and fringe events unfolds over the 12 weeks, shining a light on the city’s vibrant cultural scene.” Learn more here.

Want to know more about Stephen Yip, the charity founder running as an independent candidate to be city mayor of Liverpool in May’s election? We spoke to Yip in December and published an in-depth piece about his work, which you can read here.

The long read: Mersey Beat

…or now how Liverpool set Jack Kerouac on the road to literary stardom. By David Barnett.

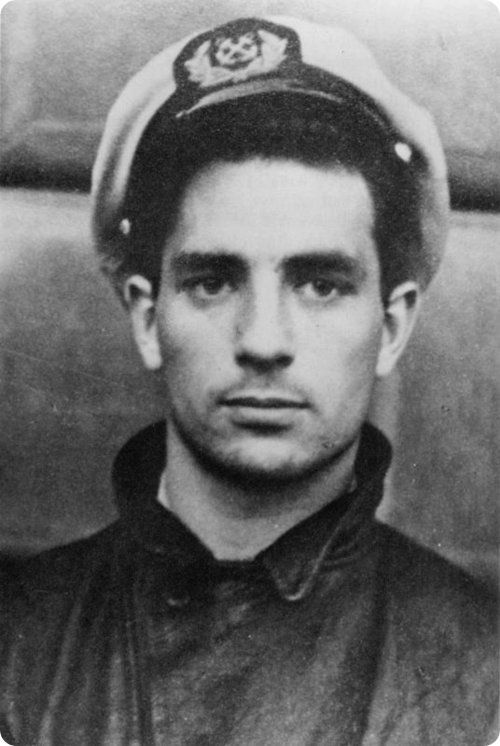

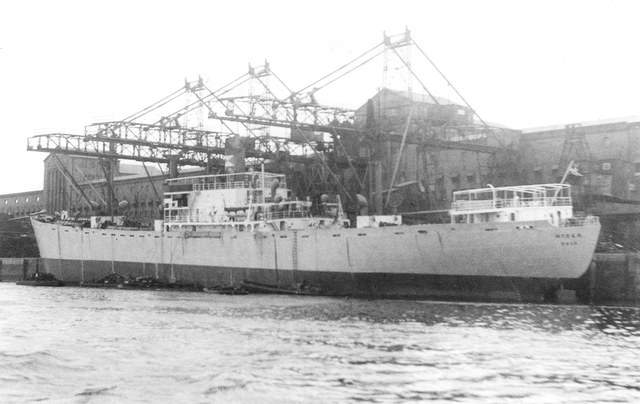

In September 1943, an American merchant navy ship, the SS George Weems, docked at Liverpool. It was carrying a cargo of 500lb bombs that it had nursed through the U-Boat infested waters of the Atlantic to be used in the war effort from Blighty.

It also had on board a young man making his first visit to Britain, whose brief time in Liverpool would set him on the road to becoming one of the most original literary talents of his generation.

Jack Kerouac is best known as the author of the 1957 novel On The Road, a fictionalised account of his own travels across America. He was a founding member of what became known as the Beat Generation, a group of men and women who were born between the wars and who eschewed the domestic boom in America in the 1940s and 1950s and instead pursued a hedonistic lifestyle of jazz, drugs, unfettered sex and writing.

The image of the Beatnik with beret and goatee, banging bongos and spouting spontaneous freeform poetry at a “happening” has become almost a cartoon, but Kerouac and his contemporaries were more complex, layered and morally ambiguous than that.

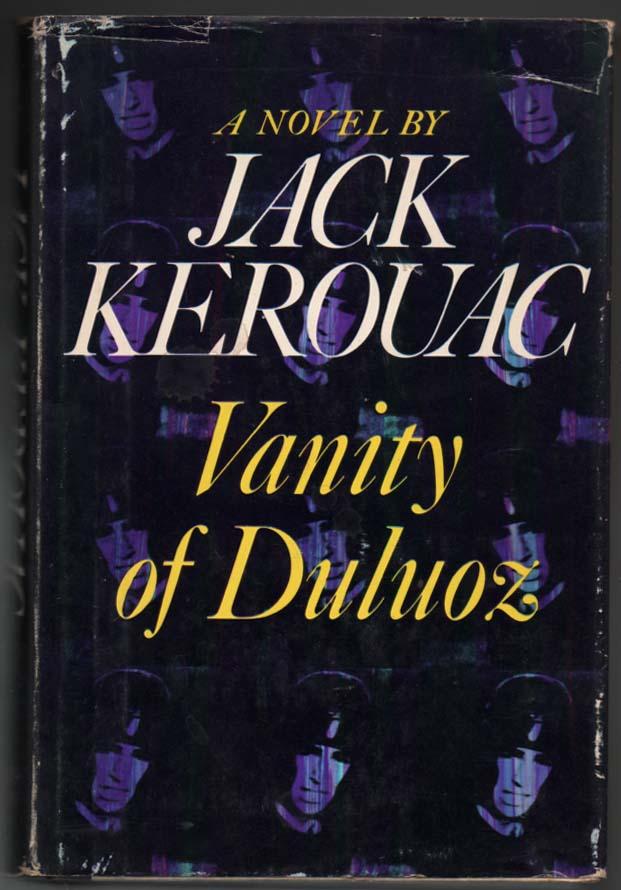

While On The Road became the Beat Generation bible, it is just one of a whole tapestry of Roman à Clef novels that Kerouac wrote up to his death in 1969, all retelling episodes from his life with thinly disguised accomplices and acquaintances. Kerouac even gave himself an alias — Duluoz — for the 13-book cycle he called The Duluoz Legend. And the idea for it was birthed in Liverpool.

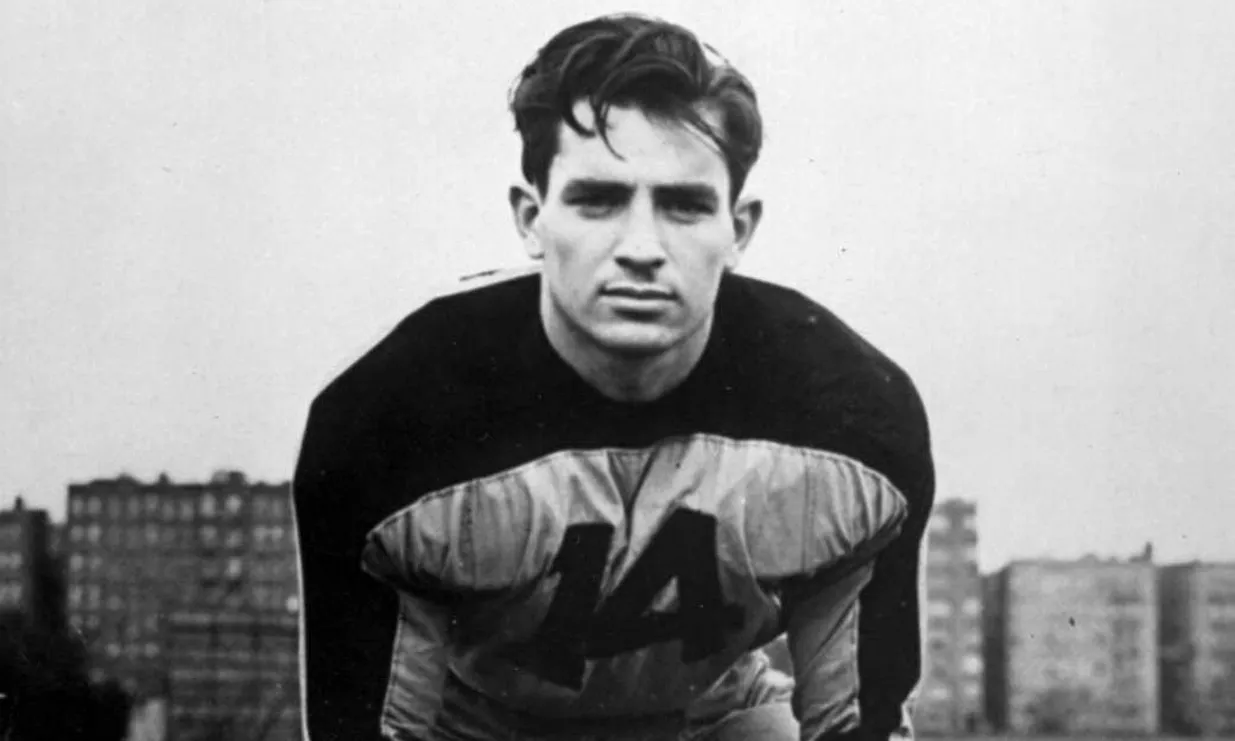

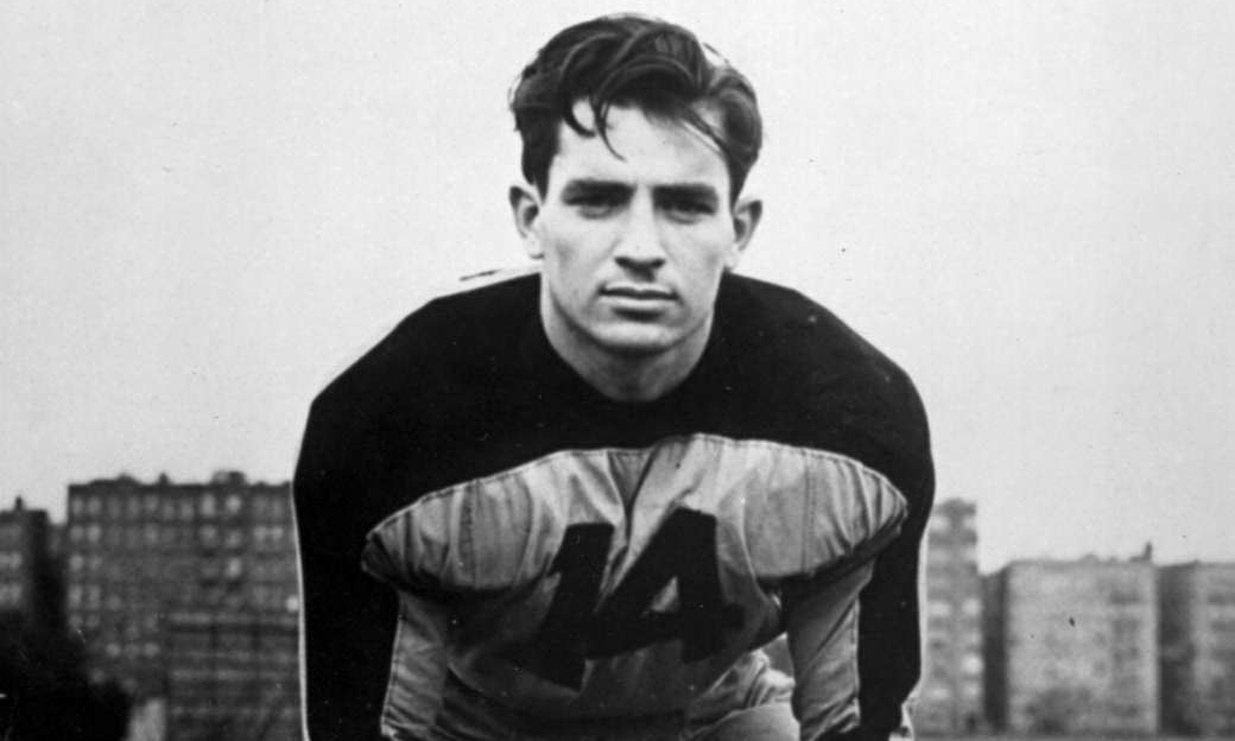

Kerouac was 21 when he made the perilous journey to England after signing on with the merchant navy. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, to a French-Canadian family, he had attended Columbia University but dropped out after a broken leg ended his football career. Living on New York’s East Side he first met the figures who would eventually form the Beat Generation witeh him — including Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady and William S Burroughs.

Thirsting for adventure and experience he first enlisted with the US Navy but lasted only eight days before they discharged him with a diagnosis of a “schizoid personality”, leading him to sign up with the merchant navy. He was assigned the role of deckhand on the SS George Weems, bound for Liverpool with its deadly cargo.

It was while at sea that he started work on his first novel, The Sea Is My Brother, but it was ultimately unsatisfactory to him and was not published until many years after his death, in 2011. But that didn’t matter, because once he arrived in Liverpool a whole new literary path opened up to him.

In fact, the whole idea of the Beat Generation could be said to have come from that trip in 1943. Kerouac’s biographer Gerald Nicosia writes in his book Memory Babe: “On his last morning in Liverpool that vision of ‘beatness’ as he later called it, prompted him to conceive of the Duluoz Legend. Sitting at his typewriter in the purser’s office he suddenly foresaw as his life’s work the creation of a ‘contemporary history record’”.

But what actually happened when Kerouac arrived in Liverpool that September in the middle of the Second World War?

On the journey over, between working on his own novel and making enemies of the first mate, Kerouac read John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga to give himself an idea of British life. Quite how the saga of an upper-class family compared to the reality of landing at Liverpool Docks Kerouac doesn’t say. He does chart his time in Liverpool in his book The Vanity of Duluoz (published in 1967), though. Here are his first impressions:

As we came up the Mersey River, all mud brown, and turned in to an old wooden dock, there was a little fellow of Great Britain waving a newspaper at me and yelling, about 100 yards ahead as we bore directly on him, he had his bicycle beside him. Finally I could see he was yelling something about ‘Yank! Hey, Yank! There’s been a great Allied victory in Salerno! Did ye know that?’

But the actual alighting in Liverpool was about to be rather dramatic… and potentially tragic, given the cargo of bombs in the hold of the SS George Weems. Kerouac shouts for the newspaper seller to clear off the dock as he can tell the ship isn’t coming to a gentle halt (he suspects the captain has been on the Schnapps). He writes:

He took off his derby and ran back with the bike he was pushing, and sure enough, the bow of the SS George S Weems carrying 500-pound bombs and flying the red dynamite flag rammed right into that rotten wood wharf and completely demolished it, ce-rack-ke-rack-crack, timbers, wood planks, nails, old rat nests, a mess of junk all upended like with a bulldozer and we came to stop in Great Britain. This sceptred isle. Now, if it had been a modern concrete job, goodbye Du Louse, the book, the whole crew and nothing but the crew, and all and all of Liverpool.

Most biographies of Kerouac make more of the fact that as part of his shore-leave, the writer took a train to explore London for a couple of days, but Nicosa’s Memory Babe offers a little about what Jack did in Liverpool… and how the city affected him.

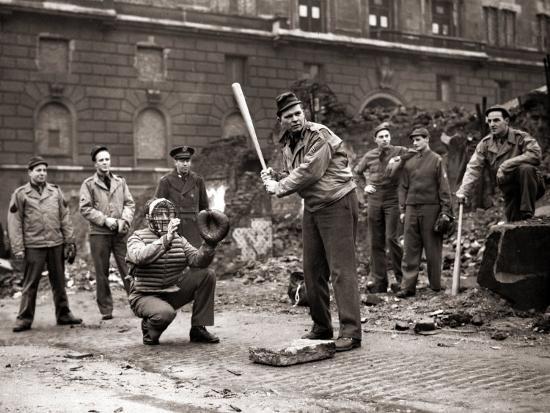

He writes: “Imitating the Lancashire accents of the longshoremen, and studying the old seadogs on neighbouring ships, he realised that some day he really might be a great writer like [Joseph] Conrad or [Herman] Melville. For his leave he dressed in a black leather jacket, khaki shirt, black tie and a visored hat with a phony gold braid.”

On his last night in Liverpool, Kerouac engages the services of a prostitute and, says Nicosia, “he had to make his way to the ship through another blackout, but he was more afraid of the English ruffians than the German bombs.”

Nicosia writes: “England had lived up to his romantic notions of its grand history and culture, but he had also been impressed by the poverty of its inhabitants: the pubs closed for lack of beer, people reputedly eating sausage made with sawdust and storing coal in their bathtubs.”

It was all this that suddenly gave Kerouac the notion of “beatness”, which was at the heart of everything he was to do after his trip to Liverpool. Beat has many meanings in this context: the beat of the jazz drums, the beat-up nothingness of poverty, the beatific, spiritual idea of eschewing the ordinary world and embracing something more spiritual yet, conversely, more physical.

All of this would make it into On The Road, and Kerouac’s other books such as The Dharma Bums, Big Sur, and Lonesome Traveller, and it all came from a short stay in Liverpool.

Joyce Johnson, who had a relationship with Kerouac, wrote in her biography of him, The Voice is All, of how Liverpool was so important in his future as a writer. She says:

On a rainy morning in late September, just as the George Weems was preparing to embark upon its return trip to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Jack had one of those epiphanies that come to writers after periods of seeming dormancy — an illumination in which he could see his entire life’s work stretch out before him. Rather than telling the stories of fictional characters, he was going to keep writing the saga of his own life as it unfolded over the years.

Kerouac only returned to Britain once, in the late 1950s after a visit to Paris to try to find his Breton forebears, and then he stayed in London. But his brief sojourn in Liverpool was deeply influential over his life and career.

So last word to Jack, from the Vanity of Duluoz: “I got a haircut downtown Liverpool, hung around the rail station, the USO club looking at magazines and pingpong players, rain, the rimed old monuments by the quay, pigeons, and the train across the strange smokepots of Birkenhead and into the heart of La Grand Bretagne… the Great Britain.”

David Barnett writes about books for The Guardian and is the author of several novels.

The Post is still early in its life. We hope to start publishing more regularly later this year — when we have the resources to build a little team.

Talented journalists in the region who would like to write for us should email editor@livpost.co.uk with their ideas. And if you have a story you think we should be covering, please get in touch by replying to this newsletter or using the email above.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, you can sign up to The Post’s free mailing list by clicking the button below.

Past Posts: In case you missed them

A nice way to start my Tuesday ☕🗞️

— Dani Cole (@danithecole) 10:53 AM ∙ Feb 16, 2021

'The whole place is so full of mysterious questions' by @liverpoolpost liverpoolpost.substack.com/p/the-whole-pl…

Fascinating story into the background to Joe Anderson’s arrest: The Georgian townhouse at the centre of Liverpool's political scandal by @liverpoolpost

— Simon Jones (@ariadneassoc) 10:55 AM ∙ Dec 19, 2020

I totally love @liverpoolpost already. Providing the best insights and features on our great city.

— James Corbett (@james_corbett) 10:37 AM ∙ Nov 27, 2020

The families on Merseyside who dread the approach of Christmas

The Brutus sailed from Liverpool on the 18th of May, carrying 330 passengers to Quebec. Three and a half weeks later it was back at port, and 82 of them were dead.

— The Post (@liverpoolpost) 3:01 PM ∙ Nov 5, 2020

A story about riots, conspiracy theories, and Liverpool in the time of cholera.

Comments

Latest

The unexpected auction: A London fund manager is selling Merseyside homes from under their tenants

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still plays every Saturday

Mersey Beat: Jack Kerouac's epiphany in the Liverpool docks

Plus, the latest Covid-19 data for the Liverpool City Region, and our Post Picks