In 1988, Steve Doran took a decorating job in Liverpool. More than 30 years later, it killed him

For the first time, we tell the story of a death caused by exposure to asbestos at Quiggins

Dear readers — today’s story is about one of Britain’s biggest killers, but not one that often gets mentioned: asbestos. It’s about a man called Steve Doran who sadly passed away last year from mesothelioma — a cancer caused by asbestos exposure — and the carelessless that took his life at Quiggins, a once-beloved indoor market in the city centre. It’s the first time Steve’s story has been told, and his family have chosen to publicise it given his desire during his illness to make people aware of what happened to him.

Editor’s note: As today’s Thursday read is about a topic we believe to be in the public interest, we have decided not to paywall it. That means it is free for everyone to read all the way through. However, if you are able to support us by signing up as a paid member for £1.25 a week, please do so today and help us do more of this kind of reporting. It wouldn’t be possible without our 1000+ paying subscribers who fund what we do. Thankyou.

When Steve Doran was first diagnosed with mesothelioma in 2019, a doctor in Barcelona told him to expect “war”. Spanish doctors can be like that perhaps; no holding hands and saying it softly. But the doctor knew what he was talking about. Mesothelioma is a horrible way to die.

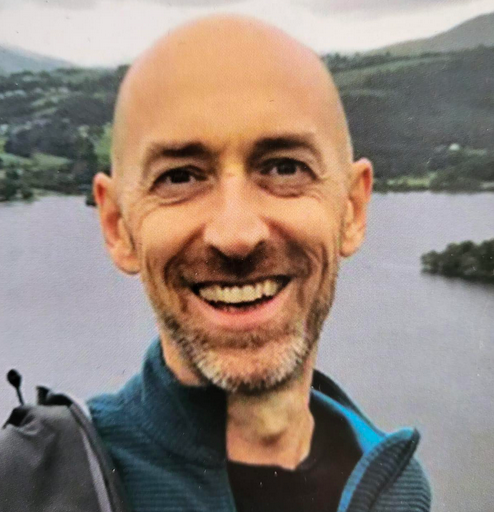

Steve, who was living in Spain at the time, was witty, smart and had high standards. A few weeks ago, I met his sister Nina in the Egg Cafe off Renshaw Street as she sat listing these traits. He was loyal, and far from materialistic; he never kept many possessions. He was someone who always saw the funny side, who “used humour to put you straight”. He was never outwardly morose, in fact he was stoic, and he didn’t like complaining or asking for things.

Mesothelioma is a form of cancer caused by asbestos. It kills 2,400 people in the UK every year (just under half of asbestos deaths), many of them in the north west, owing to the region’s legacy of factories set up to produce asbestos products from fibre shipped in from abroad. Asbestos tends to have a latency period of several decades before it causes tumours in the mesothelium, a membrane which surrounds the lungs, heart and intestines. In that way it creeps up on you, arriving suddenly and out of the blue, long after initial contact.

In Steve Doran’s case, that contact occurred in Quiggins, the once-beloved indoor market in Liverpool city centre that closed down in 2006. This article is the first time that Quiggins has been linked with an asbestos death in public — and the first time Steve’s story has been told.

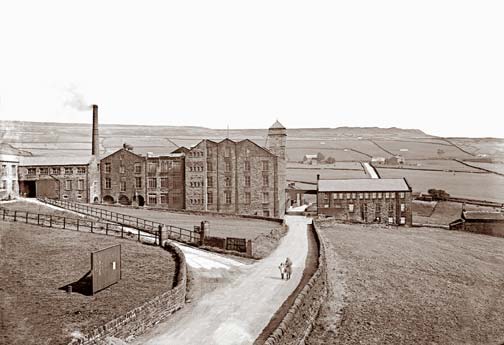

Quiggins has an interesting story in itself. Back then, it was one of the go-to places for trendy Scousers, with its rows of small alternative stores selling antiques, vintage clothing and various curios. It became a significant cultural venue in the city, home to an internet-based rock ‘n’ roll and punk radio station called Fraggle Radio, and the Brook Café, a late night live music venue.

Despite the alt vibe, its owner — businessman Peter Tierney — would end up joining the BNP, standing as a National Front candidate in Liverpool’s 2012 mayoral elections and being found guilty of assault after hitting an anti-fascist campaigner with a camera tripod at a demonstration.

But before all that, in 1988, when an earlier version of the store was moving from Renshaw Street to School Lane to service its expanding ambitions, Tierney needed a painter-decorator to come in and slap paint on some beams.

Steve’s trade back then was painting and decorating, but it was a means to an end. He played in a band called The Glad Eyes and music was his real passion. At the time, he and Nina shared a flat in Faulkner square; he was the sensible, focused one, working in the evening and playing guitar in the day, while she was the “arriving-home-as-Steve-left-for-work one”, she laughs.

Pleased to be making a bit of money, Steve took the job along with a mate. What he didn’t know then was that the beams had been sprayed with asbestos for fire protection, a practice that, three decades later, would lead to his death.

Asbestos was banned in the UK in stages; blue asbestos in 1980, brown in 1987 and white in 2000. Many people see it as a relic of the past, associated with a bygone era when heavy industry dominated the region, and when workplace health and safety was a distant afterthought. In much of the public imagination it’s as good as eradicated, like smallpox or polio.

But that’s a misconception. The truth is, you could still fill page upon page with shocking asbestos statistics. There are still six million tonnes of it present in 1.5 million UK buildings, including workplaces, public buildings — even schools — as well as in homes, according to research published in 2019 by the think tank ResPublica. The same research pointed out that our asbestos regulation is so poor that a British child can be legally exposed to 10 times as much asbestos as a German child.

Recent data from the Office for National Statistics showed that in the UK, 147 health and education workers have died from mesothelioma since 2017, proof that it is no longer just a killer of those working in industry. Every day, thirteen people die in the UK from previous exposure to asbestos ; approximately 5,000 a year. It’s Britain’s biggest workplace killer; once you’ve been diagnosed, it’s as good as terminal.

Steve’s diagnosis came in 2019, long after he’d moved away from Liverpool; first to Dublin, then Paris, then with his partner Marta to Barcelona, with whom he later had a daughter. In Spain, he’d gotten into renovation, picking up old frames and mirrors in markets, doing them up in his own little studio and selling them on. He continued his music too, singing and playing guitar under the name of Ernest Moon.

Every year he’d come home to Liverpool and the family would make their annual trip to Wales. But four years ago, it became clear that something wasn’t right; he had pains in his chest and was coughing a lot. Steve, who was barely into his 50s, protested that he was fine, but then he was “never one to ask for help with anything”. It turned out that he’d been suffering for over six months.

Eventually, after seeing several doctors in Spain and taking various tests, he was diagnosed with mesothelioma in September 2020 and offered six bouts of chemotherapy, with the possibility of surgery after that. But there were no guarantees; Steve underwent three rounds of treatment, but each one severely damaged an aspect of his quality of life; first his voice, then his hearing, then his eyesight. His body weight was waning; he decided enough was enough.

The north west of England has an asbestos legacy like virtually nowhere else. The UK has no asbestos mines so, for about 150 years, the mineral was imported. By focusing on just one importer, take the Cape Abestos Company — the massive British firm founded in 1893 to mine asbestos in the Orange Free State (now South Africa) — it’s possible to trace a chain of deaths over successive generations.

Cape owned mines that produced brown asbestos, which the company compressed into boards and shipped to Europe. First to die, of course, were the workers in those mines, who were virtually slaves. They had first-hand contact with the asbestos, and within a few decades of the factory opening up began losing their lives.

Asbestos left the mines in hessian sacks and made its way across the globe, arriving in ports like Liverpool. Workers would go into the boats, pick up the bags and carry them off, and a number of years later they started dying too. Next in the chain were workers in the factories set up to make asbestos products across the north of England, one of which, Acre Mill near Hebden Bridge, was owned by Cape. These factories made pressed asbestos boards, blankets and other products. Not only did the workers start dying, but the people who lived near the factories, especially those down-wind, did too.

The next generation of victims were those exposed when working with asbestos boards as part of their trade, often years after the material was first installed. Steve Dickens — a lawyer at the solicitors firm Leigh Day who helped secure Steve’s compensation — explains that he’s seeing an increasing number of electricians and joiners who unknowingly disturb asbestos-based materials when they’re working on site. It’s the same for people like Steve, unwittingly doing odd jobs in the presence of a proven killer.

Per capita, the UK imported more asbestos than virtually anywhere else in the world. Now, lawyers like Dickens are witnessing yet another generation of poisoned men and women, including nurses, teachers and other professionals. These are incidents caused by low-level exposures, given that much of the UK’s building stock still contains the lethal material.

In his final months, having rejected further chemotherapy, Steve “got his wits about him” and attempted to manage his illness. He changed his whole way of living, eating more healthily — wild fish and cabbage (“halfway house keto” in Nina’s words) — and doing his own research into cases where people had managed to live with mesothelioma for four or five years. But as with many mesothelioma patients, the steepness of his decline “caught him off guard”.

After a period of illness in January last year, he shed a lot of weight and got hot easily. Realising the end was near and desperate to alleviate his suffering, Steve applied for euthanasia but, given the long-winded nature of the process, knew he’d have to wait a few months. During that time he returned to England to enjoy his “last British summer” close to friends and family, and stayed with Nina, living together as they had years before in Faulkner Square.

They visited Wales one last time, had a comic day out in Sefton Park after rushing to get Steve a wheelchair at short notice, so rickety he flatly refused to get in it. Then he returned to Spain and died in November. Three days later the euthanasia documents came through. Nina doesn’t believe he’d have gone through with it; “He wasn’t ready to go.”

In many cases — as in Steve’s — the trauma of illness runs parallel tracks to an exhausting fight for justice in the form of compensation. In that respect Steve was one of the luckier ones: he knew almost straight away where the exposure had occurred. Dickens says he has cases on his desk from the mid-1960s, often of men with fading memories whose entire working lives were spent in heavy industry. Finding exactly where the exposure occurred in such cases can be impossible.

Nevertheless, the insurance company they were up against initially pushed back. “They have a commercial approach of course,” says Dickens. “They’ll only pay out when there’s hard proof. That puts a lot of people in a tough position during serious illness”. Thankfully, it was possible to identify two men who were on site when Quiggins was demolished to make way for Liverpool ONE in 2007 and who could testify that asbestos-based material was still present at that time.

At that point, the insurance company had to abandon their defence; before his death, Steve was awarded a £315,000 payout. It was an important victory, but to Steve it felt like “blood money” and seemed to represent a perverse corporate estimation of the value of someone’s life.

John Flanagan, who for the last three decades has run the Merseyside Asbestos Victim Support Group (MAVSG), was at Steve and Nina’s side throughout their ordeal. MAVSG was started in 1993 when workers at the Liverpool Occupational Health Partnership — which Flanagan chaired — were interviewing people in GP surgeries prior to their appointments. They began noticing just how many asbestos-related illnesses were linked to the docks.

Back then Flanagan says, things were very different. “Doctors would basically call people in and say: ‘Sit down Mr Banks, I’ve got some really bad news. You’ve got this many months, now go home and get your affairs in order.’” Many people had no idea they could claim for compensation, or that there was any kind of support available at all. MAVSG became that support network.

In Flanagan’s role, you try to keep your emotions at bay; most of the mesothelioma patients he meets will die within a few years, and his job is to support them, particularly in their fight for compensation. Sometimes though, that emotional distance collapses. One woman in her 60s left him a card that read: “Dear John, I’d just like to thank you for everything. Here’s £10 to get yourself a few drinks”. She left the £10 note in the card and died a fortnight later. “I still can’t read that letter publicly,” he says. “She was basically saying — ‘I’ll be off now, have a drink on me, cheers.’ She had more bottle than I’d ever have.”

We don’t know what Steve’s employer at Quiggins, Peter Tierney, was thinking when he allowed workers to be exposed to asbestos — we haven’t been able to track him down to get his response to this article. We do know that thousands of employers in this country exhibited a calllous disregard to the dangers of asbestos in the rush to get a job done quickly and cheaply, often leading to the painful deaths of workers.

For Dickens, any defence based of ignorance simply doesn’t wash. While the whole 20th century was a gradual awakening to the horrors of asbestos, by 1988 — when Steve first walked into Quiggins — the facts were already irrefutable. As far back as 1931, the government had introduced a law to ensure employers undertook steps to prevent exposure, and in the late 1950s a South African physician called John Christopher Wagner came to the UK and told the big manufacturers — who previously believed the substance was only dangerous in large amounts — that they had a serious problem.

In a front page article on 31 October 1965, The Sunday Times reported on research linking mesothelioma and “domestic” exposure to low levels of asbestos including from clothing. It was a watershed moment; from then on, no employer could reasonably claim they weren’t aware of the risks. And in 1987, one year before Steve Doran walked through the door of Quiggins, the Control of Asbestos at Work regulations introduced even greater protection for employees at work.

Various efforts have been made and campaigns launched to have asbestos entirely removed from Britain’s building stock, or at least from its schools, but to no great effect. The conclusions of the parliamentary work and pensions committee’s inquiry into the matter last year suggested the UK set out a 40-year programme for removing all asbestos from public buildings. The government rejected the proposal. “There is no great appetite to go out and remove it,” Dickens says.

As Nina said in her speech at his memorial, “Steve had to endure his impending death knowing that it was caused by being unnecessarily exposed to a poisonous dust.”

Just before publishing this story, I heard from Marta, Steve’s longtime partner. She tells me that as Steve’s life wound down, he was too exhausted to publiclise his case. “He wanted to do it but he was too tired because of the illness,” she says, remembering his desire to make other people aware of what had happened to him. “That is one of the reasons we are doing the article.”

Specifically, Steve wanted his family to share the documents that allowed him to win his compensation with other people who might have worked in the same building. “He was lucky enough to get that paper,” Marta says. “Most of the people with mesothelioma do not see any money, and if they see it it is too late.” Most, she says, are too tired or too poor to get into protracted wrangles with powerful teams of lawyers, and the insurance companies know this.

What hurts her the most isn’t just that Steve died of an aggressive and painful cancer, although of course he did. It’s the sense that he died not from the arrival of an unforeseen illness, an unlucky turn in life’s strange lottery, but a cancer that was inflicted on him. A death by what she calls “a lack of care.”

Please do share this story with friends — by forwarding it or hitting the share button above.

Comments

Latest

Berlin, Rome, Bruges and...Liverpool. The city brings in its tourist tax

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

In 1988, Steve Doran took a decorating job in Liverpool. More than 30 years later, it killed him

For the first time, we tell the story of a death caused by exposure to asbestos at Quiggins