How to save 40,000 lives

A groundbreaking approach to preventing suicides on the Wirral

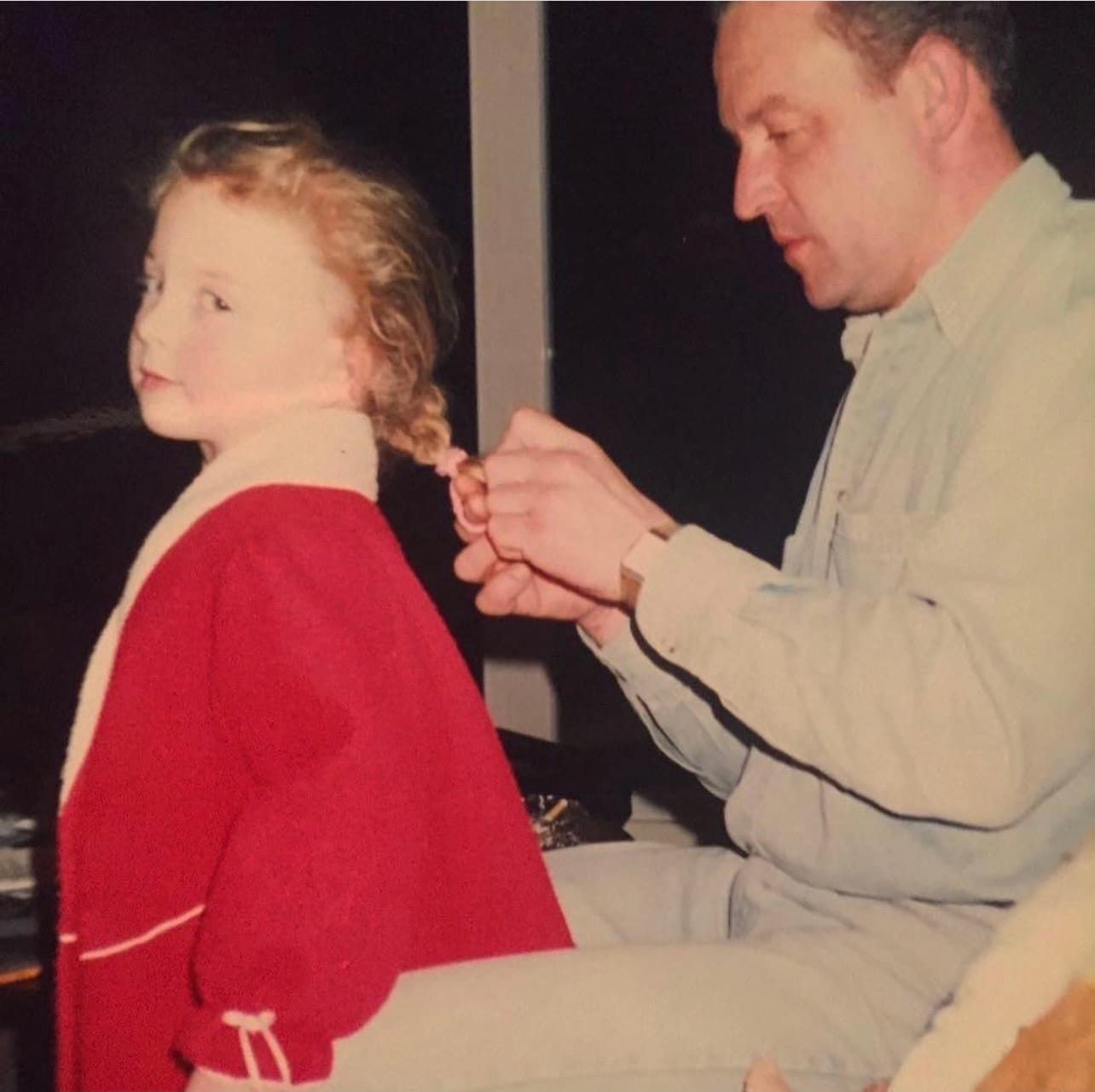

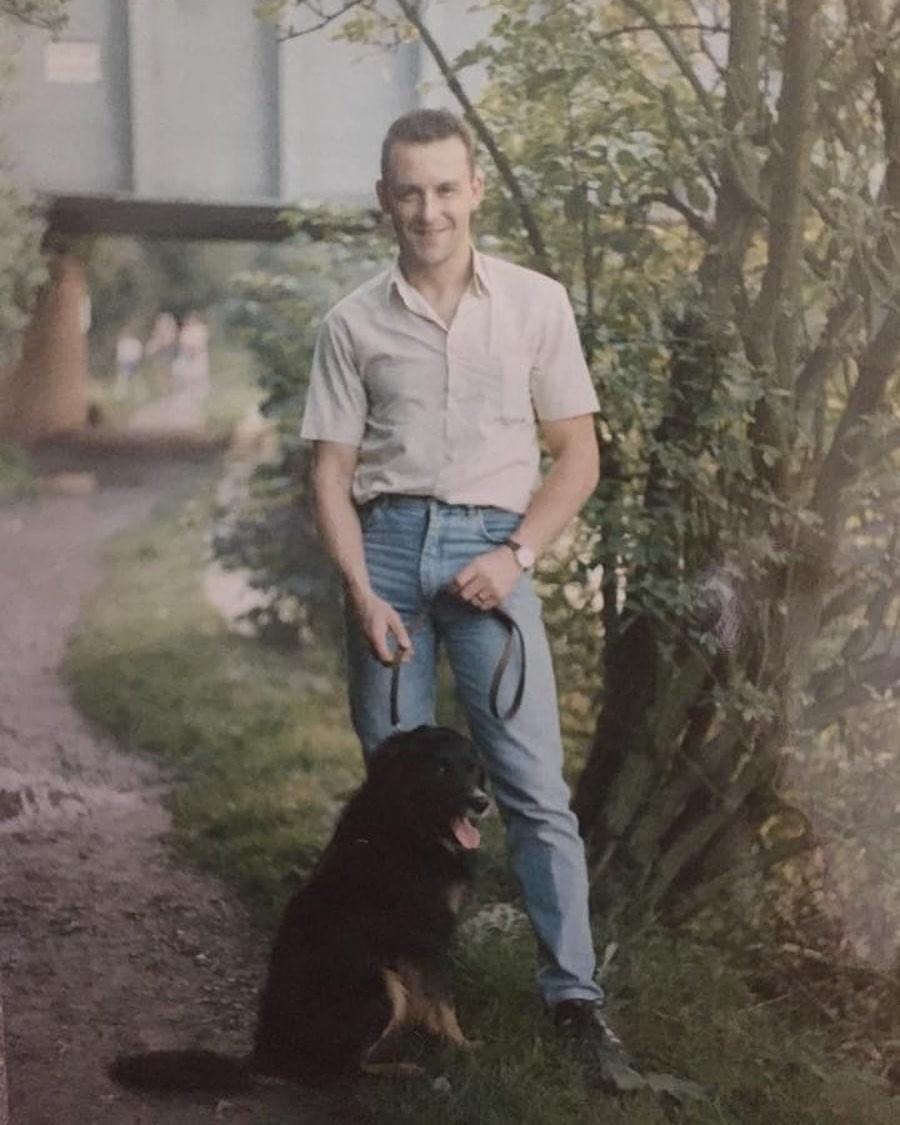

When Martin Gallier died by suicide in 2017, his daughter Jess was 26 years old. “A lot of people say they didn’t see it coming,” she tells me. “We did. We just didn’t have the toolkit to prevent it.”

Jess was a new mum to a three-month-old at the time; the euphoria of early parenthood was quickly subsumed by grief, while the ensuing pantomime of coronial inquests only protracted her misery. She thought she would walk into the coroner’s court and be told her father had died by suicide — end of story. But he was, in her words, “a complicated man”, and his case wasn’t clear-cut.

Martin had previously attempted suicide and was known to health services. The inquest concluded those responsible for his care had missed crucial opportunities to prevent his death because of simple things like overflowing waiting lists and unmet criteria for services. Jess, who was de facto spokesperson for her family during the inquest, had an epiphany on the fifth and final day. “I just thought, isn’t there a better way to do this?”

Jess’s vision was to build a suicide intervention service in her father’s name which would plug all the gaps he had slipped through. At first, her family were unsure what a new service could add that the likes of Samaritans weren’t doing already. But watching the coroner deconstruct her father’s death had given Jess the impetus to act. “I’d seen too much, I’d heard too much, I’d felt too much to leave it alone,” she says. “It was like a scab that I kept picking at. And in my darkest days it truly kept me alive.”

In February 2019, a year almost to the day from the end of the inquest, The Martin Gallier Project (MGP) opened their centre in New Ferry. Four days later, they saved their first life.

Outside the building on New Chester Road, a white, heart-shaped cloud is painted over blue bricks and seems to drift between the windows. The mural, one of a series in New Ferry by Scouse artist Paul Curtis, pays tribute to the village where 81 were injured in a 2017 gas explosion. Printed on a black sign beneath this striking vista are the logo and the slogan: “Preventing Suicides, Breaking Down Stigmas and Supporting Families in the North West.”

MGP has made good on that promise: in six years, this non-clinical, community-embedded charity has saved over 41,000 lives. And unlike many suicide hotlines and national charity operations, MGP offers support far beyond the moment of crisis - it’s the only suicide prevention, intervention and postvention service in the North West of England. By designing person-centred care plans, arranging check-ins and helping clients access therapy, education and employment, they don’t just minimise the risk of death, but maximise the potential for life. Some clients even go on to become employees. The team has grown to 26 full-time suicide intervention workers (SIW), supported by an ancillary team of around 50 volunteers. They are open seven days a week and support anyone over 16. Their oldest client is 87.

Last month, MGP was highly commended at the Health Service Journal Awards as the ‘Best Not for Profit Working in Partnership’ with the NHS. That partnership is the first of its kind in the UK, designed to ‘bridge the gap’ for people presenting at A&E with thoughts of suicide by referring them to MGP for one-on-one support. The initiative has led to an astonishing 69% decrease in A&E attendance of individuals in suicidal crisis. What is it about MGP’s approach that’s made it so successful at saving lives?

‘The magic is staying safe for now’

Everybody in the building, even the administrators, are trained in Applied Suicide Intervention Skills (ASIST), Jess explains. “People walk in and it’s really hard to ask for help, isn’t it? It’s easy to change your mind and walk out. So it’s really important that the first conversation you have when you walk through that door is the right one.”

ASIST, developed in 1983 by Canadian public services body LivingWorks, is a two-day course which teaches participants to recognise and intervene with individuals at risk of suicide, providing them with the practical skills to save lives.

When an individual in a crisis contacts the group, an SIW will take first steps to disable the suicide plan. This means doing a sweep, disposing of the means, removing the immediate risk. They engage in talk therapy with the client and identify things they feel positive about. If there are no positives, that’s fine — they’ll keep engaging, talking, listening for a measure of doubt in their reasoning, probing for uncertainties. Even something as simple as the word ‘but’ is a lifeboat, something to latch onto. “If they say ‘It feels like there’s no other way’, you say, ‘if I could show you another way, would you be interested?’”

The next stage is to collaborate on a short-term plan, focused on simple steps that can keep them alive until the next meeting. “Three days, six weeks, whatever they can do,” says Jess. “The magic is staying safe for now.” This process repeats every time the SIW and the client meet. Once the client reaches a point where they can stay safe indefinitely, they begin ‘postvention’. This involves adding additional layers of support and enrichment through workshops and sociable activities. MGP programmes include Martin’s Man Cave, a Sunday peer support group for men which offers cooking sessions, walking groups, meditation and adventure trips. For women, Self Care Movement has classes on creating positive body image, vision boards and art. Reaching the LGBTQ+ community is their group Belong, while Forget Me Not supports bereaved families - who are disproportionately more likely to die by suicide after losing someone to it.

‘I’m achieving things I never thought I could do’

Mike, 32, from the Wirral, is studying Psychology at University of Chester. He is ASIST-trained and volunteers for MGP every Wednesday afternoon, conducting Recovery Star workshops, which examine the areas that bring an individual to crisis point in the first place. Mike first came to MGP during his own crisis. “In a way, I’ve always been a suicide intervention worker,” he tells me. “I was always helping other people in my life who were suicidal, in school, at home. Weird as fuck that I was telling other people to get help but didn’t know how to help myself.”

Mike’s childhood was punctuated by traumas. Before he turned four, his father had made multiple attempts on his life. His mother remarried but had struggles with alcohol, and Mike later lived with an aunt and uncle. During his “nightmarish” teenage years, he was sexually abused. In adulthood he struggled to settle, finding maintenance work on the overhead power lines before relocating to Crewe for a position at an electronics retailer. He ended up back on the Wirral aged 24, and had a relationship which became toxic and abusive. By 2019, he was in a YMCA homeless shelter. This is where he spent lockdown.

When he finally found stable accommodation after restrictions eased, Mike was still struggling with suicidal ideation. NHS Talking Together put him in touch with MGP. “I went in there with no expectations,” he says. They set him up to attend a ten-week course of workshops and arranged a counsellor for him, Claire, who “weaved her magic”. Mike had shown interest in becoming a counsellor himself, so she encouraged him to take an ‘introduction to psychology’ module at Wirral Met College, after which he progressed to Chester University.

Mike is honest: he still struggles with a lot of anger, and admits his recovery hasn’t been plain sailing. He finds himself becoming frustrated in big groups, and he has lashed out verbally when misunderstood by peers in college. But every Wednesday, when he volunteers with MGP, he says his soul heals. “I feel like I’m getting a little bit better every week. I’m working in mental health, I’m in university, I’m achieving things I never thought I would do.”

Tackling the suicide taboo

Jess’s fundamental goal is to treat suicide as its own area of preventative focus, rather than lumping it in with a more general mental health conversation. “I see it even now,” she says. “Sometimes when journalists are writing stories [about MGP], they’ll refer to it as mental health, mental health, mental health —but we’re not just talking about mental health. Yes, there’s a crossover – but we’re talking about suicide: why are you scared of the word? The only place where there’s no resistance is the people that need it.”

One reason there’s a culture of silence around suicide is the perceived fear that talking about it with someone might ‘plant the idea’ – a fear Jess strongly rejects as “nonsense”, as does the NHS website. In the public realm, talking about suicide clearly and directly is actually a proven way to prevent it, because it opens people up to the relief of sharing, being supported and discussing solutions. Talking about specific suicidal methods, however, is dangerous. This distinction is often misunderstood.

An audit by Wirral Council’s Public Health Intelligence Team showed that 40% of people who died by suicide between 2020-22 were unknown to mental health services, while only 15% had prior detentions under the Mental Health Act. Physical health problems were the most common factor in these people’s deaths, and in 12% of cases the individual had chronic or terminal illness. Risk factors for suicide can go far beyond what we typically think of as “mental health.”

Understanding risk factors

Jess also points out that elderly, disabled and marginalised individuals are often forgotten when public discourse around suicide remains laser-focused on mental health. The British Medical Journal confirms as much: the risk of death from suicide is at least twice as high in those with chronic pain, while Disability Rights UK report that disabled men are three times more likely to die by suicide than able-bodied men – while for disabled women, the increase is fourfold.

MGP introduced specialist training for all staff during COVID when SIWs noticed a sharp increase in clients experiencing domestic violence. One in five people who died by suicide on the Wirral between 2020–2022 had a history of domestic abuse, and this issue tracks nationwide: between 2020-2024 there were 1,012 domestic abuse related deaths and a third of them were classified as suspected victim suicide following domestic abuse (SVSDA).

Poverty can also play a significant role. 25% of the Wirral falls within the 10% most deprived areas of the country. The use of foodbanks on the peninsula has increased from less than 1,000 (2011) to over 15,000 (2024) and 35% of these parcels went to households with children. A 2024 Food Foundation report found that food insecurity – in particular, parents being unable to feed their kids – creates a persistent state of stress which “can impair cognitive functions, disrupt sleep and exacerbate pre-existing mental health conditions, sometimes heightening the risk of suicide attempts.”

‘I tried to do everything myself’

Dave, 57, also from the Wirral, is known to mental health services after previous crises. “Got a few problems in the noodle,” he tells me. “Couple of suicide attempts, and I’ve been on the watch list for about three years.” He is a recovering alcoholic and was recently housed after a period of homelessness. He also had a mini-stroke in January and suffers every day with painful arthritis, which can leave him immobile for hours at a time. Dave first came into MGP’s orbit last year.

Dave had been living in the North East but moved back to Wallasey to live with his brother in 2021 following a divorce. He was already struggling with alcoholism, and his brother’s chaotic lifestyle sent him into a nosedive. Within a year, he was sleeping rough. One night, police picked him up and took him to the YMCA homeless shelter. With the help of MGP and other local charities, he eventually got himself set up with supported housing.

A SIW calls Dave twice a week. Part of their arrangement is that he never knows when. This isn’t a standard of MGP; it was written into his bespoke plan because this is what’s most effective for Dave. He doesn’t cope well with the anxiety of knowing a call is coming at a certain time of day, and this pressure may force him to act irrationally, or ignore it, or pretend to be OK when he’s not. Now, he can go about his business and the phone calls become just a pleasant surprise, like a friend calling for a chat. And it works.

The only thing Dave regrets is taking so long to come around to talking openly and building up a support network. Like a lot of men, he feared admitting he was at rock bottom, or telling anyone he was considering suicide. “What I didn’t do was go out and look for help," he tells me. "I have this thing about failure. I didn’t go through rehab, I tried to do everything myself. We weren’t brought up discussing stuff like this. Even now, sometimes I blush.”

How to save a life

The statistics are clear: between 70% and 80% of suicides every year are men. MGP’s base is weighted a little more evenly: 40% of their clients are female. In Jess’ experience, men and women seek support for suicidal thoughts in different ways. Women generally seek help earlier on, whereas men will tend to come when things have got “more intense” and there’s less time to work with. She fears an overemphasis on stats distracts from the main mission. A rising tide lifts all boats, and her priority is to give people the tools to deal with and communicate about suicide, irrespective of their gender or background.

MGP has expanded to cover four locations – Wirral, Cheshire, Macclesfield and Crewe – but Jess says it’s never enough. “We’ll open one on the moon if we have to.” She wants everyone to know ASIST: teachers, healthcare professionals, university students. Since 2021, MGP has delivered training in schools to teach staff and pupils the signs of suicidal ideation and the correct responses. Liverpool John Moores University are exploring crediting MGP’s approach as a crisis intervention model in its own right. Jess has been to Parliament to push for a debate about putting suicide prevention on the national curriculum.

Speak-up culture, she says, has been great for society. But people are still not educated with the answers, and they still fear the S-word. If your friend tells you they are considering suicide, what happens next? What do you do with that disclosure? “If we’d known some of that basic stuff back then, my dad would still be here,” she says. “And if I had a magic wand, I would educate the whole world so that everyone knows what to do.”

Comments

Latest

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

The Pool of Life

How to save 40,000 lives

A groundbreaking approach to preventing suicides on the Wirral