Hellraiser: Clive Barker on sex, art, and death

The author and filmmaker tells The Post about growing up gay in Liverpool, witnessing disaster, and the power of imagination

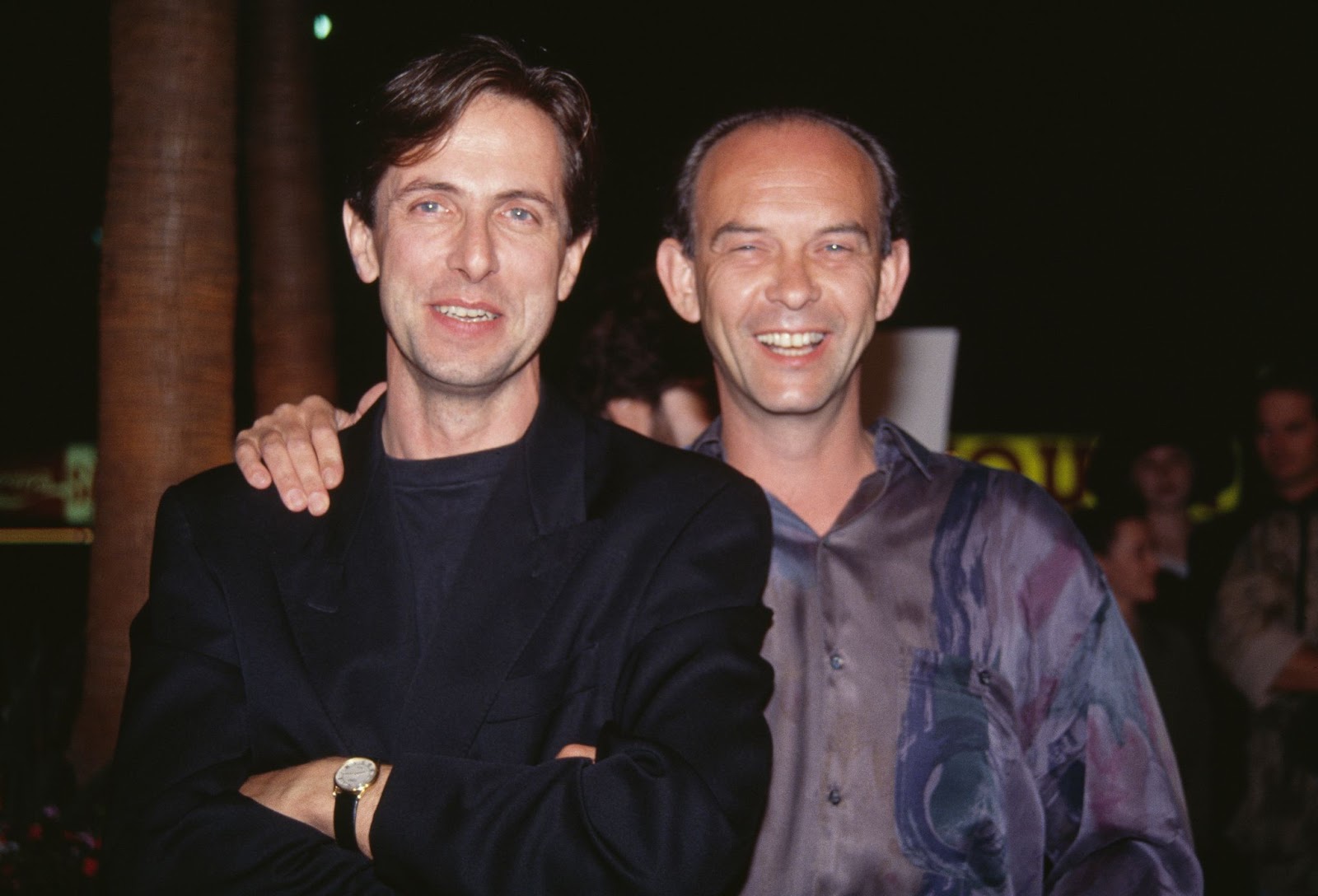

Dear members — Today’s edition is devoted to a fascinating chat between Laurence and one of his greatest early inspirations, the talented multi-hyphenate Clive Barker. Born in Liverpool in 1952, Barker is best known for the film Hellraiser, which he adapted from his own novella “The Hellbound Heart”, and for Bernard Rose’s Candyman, derived from his short story “The Forbidden”. Although the latter film was famously set in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing development, Barker’s original tale concerned a dilapidated Liverpool estate.

Even if you aren’t a horror fan, there’s plenty to learn from Barker’s particular approach to the artistic process, which has empowered him to create hundreds of powerful works across many mediums and genres for decades now. He thinks everyone is capable of harnessing “the creative energy in the cosmos”.

Your Post Briefing

In the Southport stabbing trial, Axel Rudakubana has pleaded guilty to the murders of Bebe King, six, Alice da Silva Aguiar, nine, and Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven, and trying to kill eight other children and two adults. It has also emerged during the trial that Rudakubana bought a cache of deadly weapons online at least two years before the murder, including items used in the production of ricin, a lethal toxin. Police found ricin in Rudakubana’s house, along with a PDF file entitled “Military Studies in the Jihad Against the Tyrants: The Al Qaeda Training Manual.” The Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has announced a public inquiry will be held into the attacks, and said it was a “total disgrace” Rudakubana was able to buy a knife on Amazon aged 17. He had also been referred to Prevent, the government’s highly controversial counterterrorism programme, three times between the ages of 13 and 14 because of his fixation on violence. Merseyside Police have said Rudakubana’s online profile reflects an interest in terrorism, violence, and genocide, but not an adherence to a particular religion or political ideology.

Wirral “requires improvement” when it comes to ensuring people have access to adult social care and support, according to a new report by the Care Quality Commission (CQC). “The local authority needed to do more to look ahead to the changing demographic in their area in order to reduce health inequalities,” says James Bullion, CQC’s chief inspector of adult social care and integrated care, “such as the 12.6 year difference in life expectancy between areas of deprivation and the rest of the borough.” He added that the borough is “aware of the areas where improvements are needed but should be pleased with the positive findings in our assessment and the foundation they’ve built. We look forward to seeing their progress and hope they build on the work already underway.”

And almost 10,000 trees are due to be planted in Sefton this year in a bid to tackle climate change. Trees will be planted on nearly 80 hectares of land in Lunt, recently purchased from Sefton Council by the National Trust. The planting is part of a new programme by the National Trust (partly funded by The Mersey Forest’s Trees for Climate), which aims to create over 500 hectares of new woodlands and woody habitats across England over the next few years. Paul Nolan, chair of England’s Community Forests and director of The Mersey Forest, told the BBC that increasing tree cover is “vital for our health and wellbeing”, adding that trees can help alleviate flooding, prevent soil erosion and cut pollution in nearby cities.

On Pentecost Monday in 1956, a hundred thousand excited spectators gathered at Speke Airport, eyes fixed upon the sky above. They were waiting to see Léo Valentin, the French adventurer who had wowed audiences worldwide with his death-defying stunts.

A thirteen-year-old Paul McCartney was there, as was George Harrison. So was three-year-old Clive Barker, holding his father’s hand.

“We were stood outside the fence because we didn’t have the money to get in,” Barker remembers almost 70 years later. “The plane was just a dot in the sky.”

Valentin was a daredevil skydiver, free-falling from aeroplanes and attempting flight using wooden imitations of bird wings. This time, however, something went wrong. When Valentin tried exiting the plane, one of his ‘wings’ broke. The skydiver’s back-up parachute failed to deploy, and he fell to his death in a cornfield, landing not 10 yards from where the young Barker was standing.

“That was incredibly potent,” Barker tells me, his once nimble, mellifluous voice now a hypnotic rasp after several surgeries to remove throat polyps. “It made me who I am.” Indeed, the terror and the trauma of that formative episode is, for long-time readers of Barker’s work, almost a clef to his romans — even those stories that don’t reference it directly seem imbued with the anecdote’s uncanny power.

For the last three decades, Clive Barker has lived in Los Angeles, but he was born in Liverpool in 1952, to parents who lived on Oakdale Road off a pre-fame Penny Lane. He’s most well known for the film Hellraiser, which he adapted from his own novella “The Hellbound Heart”, and for Bernard Rose’s Candyman, derived from his short story “The Forbidden” – part of the Books of Blood anthologies that took horror literature by storm in the mid-1980s. He went on to direct Nightbreed (1990) and Lord of Illusions (1995). As well as being a fiction writer and film director, he’s a playwright, theatre director, painter, and even a video games developer. Stephen King once declared that “[Barker] makes the rest of us look like we’ve been asleep for the past ten years,” claiming Barker was the future of horror.

Like The Beatles, Barker’s name recognition extends far beyond the city even if, I will soon discover, he is undeniably of the city. He tells me several times how happy he is to speak to a fellow Merseysider after so many years.

Our conversation takes place via Zoom — a mid-afternoon chat for Barker, a dark midnight séance in the dead of winter for me. He’s a less than ideal interview subject because of how pleasant he is: asking me just as many questions as I ask him. After wasting precious interview time discussing our pets (we both own German shepherds), I ask Barker about his early artistic influences such as Jean Cocteau, the French poet, designer, film director, and visual artist.

“[Cocteau was] huge,” Barker says. “My first encounter with him was having the flu and being next door to a telly — we didn’t have a telly, but next door did — and this French guy comes on an afternoon chat show speaking a language I didn’t understand, but it was translated fully. And it was Cocteau. I was eight years old. But I was just so transfixed by him.”

Barker was initially happy at primary school, attending Dovedale in Mossley Hill. “I really loved it,” he tells me. Then he went to Quarry Bank, opposite Calderstones in Allerton. “I had a miserable time, for a long time. There was a lot of bullying, and I was a slightly overweight, short-sighted swot. I was very introverted — very, very, very quiet most of the time. And it wasn’t until I fell in love with another boy when I made sense to [myself].”

That was 1967, and he was 15 years old – “not an ideal time to be gay,” he says. “Which is why, as soon as I got the chance, I was an out, gay author, and hopefully useful to people.”

Cocteau’s multidisciplinary confidence is an ethos Barker shares to this day. “I think there’s no point in saying, ‘I can’t do this’. There’s no value in saying, ‘this is beyond me’.” He tells me of his paintings, an underappreciated aspect of his overall creative output: “I have 500 of them in the house that I’d love to show you... How often are you in California?”

Barker’s novels include the children’s book The Thief of Always; the young-adult series The Books of Abarat; and the dark fantasy novels Imajica – often considered his masterpiece – and Weaveworld – set in Liverpool, the Wirral, and in another dimension contained within a carpet. These 80s and 90s works secured Barker’s reputation. In fact, writer and critic Stephen Thrower – with the band Coil when they recorded the original (rejected, for being commercially unviable) Hellraiser score – said the genre never lived up to the challenge Barker set it in the 1980s. Beyond horror, his imprint on the wider culture is vast: by the early 2000s, transgressive author Dennis Cooper saw Baker’s influence on rock videos, cult TV, goth fashion, industrial music, and “self-evident(ly)” film and television more broadly.

I grew up reading Barker’s works, introduced in my early teens to a phantasmagorical world of gore and wonder by my perhaps too-enthusiastic uncle. The dread excitement of The Great and Secret Show and the queer sexual frisson of Sacrament provided some of the most thrilling reads of my formative years. Like my uncle, Barker felt the need to leave Merseyside to find acceptance as a gay man.

“I came out to my father on a Sunday morning when he was reading The Sunday Times,” Barker tells me. “And he never even lowered the newspaper. He just stayed silent until I left. He was of a generation that found that subject antithetical to his politics.”

In his 20s, and even in his 30s, after the Books of Blood revolutionised horror literature, Barker struggled to make ends meet. “When I was 31, I was on the dole,” he tells me. “Books of Blood had only made me £2,000. I wrote Weaveworld on spec.” During this period, he also engaged in sex work for survival.

Later, he would become involved in the sadomasochism scene, attending underground New York clubs like Cellblock 28. “No drink, no drugs, they played it very straight,” he wrote in the Guardian in 2017. “It was the first time I ever saw people pierced for fun. It was the first time I saw blood spilt.”

Those experiences informed Hellraiser. Dissatisfied with previous film adaptations of his work, Barker agreed to a sub-$1 million budget on the proviso he could direct the film himself. (He attempted to borrow a book on filmmaking from a library in Crouch End, but it was out on loan.) Nevertheless, the story of Frank Cotton, a man determined to experience the ultimate sexual pleasure, and the image of the terrifying, BDSM-influenced Cenobite monsters (the leader of whom, sometimes known as “Pinhead”, was played by Barker’s old Quarry Bank schoolmate Doug Bradley) thrilled and scandalised audiences. The film grossed $30 million worldwide and spawned ten sequels.

When Fact screened Barker’s original around Halloween 2023, I was amazed how well it held up – Frank’s resurrection scene is one of the most pleasingly disgusting things I’ve ever seen committed to celluloid. But even the most committed fan would confess that the sequels are of variable quality, and I’ve never watched past the third instalment.

“The Weinstein brothers made, I think, nine Hellraiser sequels,” Barker tells me, “and Bob Weinstein could not pronounce the word ‘Cenobite’.”

For some reason, sometime in my 20s, I put away what I considered adolescent things. I became more interested in works Barker was influenced by, like the books of William S. Burroughs, as well as the works he influenced, like Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, rather than Barker himself.

The wider culture seemed to turn away from Barker, too. He hasn’t written or directed a film since 1995’s Lord of Illusions. His post-2000 novels, such as Mister B. Gone and The Scarlet Gospels, did not receive the same ecstatic press as his earlier work. His proposed Book of the Art trilogy that began with The Great and Secret Show (1989) still awaits its final volume. He even seems to have been forgotten in his home city: the day after our interview, I head into Waterstones in Liverpool One, and search across the local author, horror, science fiction and fantasy sections for Barker’s novels in vain.

But maybe that’s beginning to change. In 2018, culture critic Matthew Monagle asked whether Barker had begun to pass John Carpenter as the horror icon to emulate, citing movies like Baskin (2015), The Void (2016), and Mandy (2018) as films that bear his indelible influence. In Netflix’s The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (2018-2020), around 150 of Barker’s paintings were used as part of the set design. An anthology film version of The Books of Blood followed in 2020. That year, Barker regained the rights to the Hellraiser films, and he produced the subsequent 2022 reboot that has been called the best since the 1989 original. In 2021, Jordan Peele, the horror auteur de jour, co-wrote the screenplay for and produced a direct sequel to 1992’s Candyman.

Amidst this revived interest in his visionary work, Barker has mostly retired from public appearances to concentrate on his art and writing. “I’m 72, and I think I’ve got another 20 years in me,” he says. “And I want to fill them with stories and painting.” He tells me he has a collection of 250 poems coming out in 2025.

Returning to Barker’s novels and stories in preparation for this interview, I’m pleasantly surprised to discover prose that’s accessible but nonetheless clean of commonplace phrases, and even possessing a musical cadence.

“Thank you for [saying] that,” Barker says. “Poetry is an important part of the prose of horror.”

He reads to me from “Human Remains”, one of those Books of Blood stories that merit comparison with the best in the genre. Like he said of Cocteau’s work, it is beautiful, elegant, and terrifying, dealing with the ordinary and the transcendent with equal alacrity and grace. His work is so visually strong, I have to ask whether he “sees” the image in his mind’s eye before transcribing it onto the page.

“No. Never,” he says. “Paul Klee said drawing is taking a line for a walk. I think writing is the same thing. I take a sentence for a walk and, if I’m lucky… very rarely, but sometimes, I will have the feeling that I know how this is going to end. Weaveworld, for instance, begins with ‘Nothing ever begins’, and ends with, ‘This story, having no beginning, will have no end.’” He adds that “creation of any kind – painting, writing, poetry – is a very mysterious process.”

He thinks everyone is capable of harnessing “the creative energy in the cosmos,” but “our culture makes us lazy. If it’s a choice between coming home from work, getting a blank piece of paper and trying to write something, or turning on the telly… Writing is difficult.”

Barker’s voice has begun to fade, and he apologises for drawing the interview to a close. There’s no need: he’s been absurdly generous with his time over two days now. I thank him, and with embarrassment rising, confess that he was my Cocteau: all my early attempts at writing were imitations of his work.

“I’m crying,” he says delightedly. “Thank you.”

Comments