Goodbye, Goodison Park

Everton’s historic stadium has been at the heart of the community for 13 decades. Can the local area — and Everton itself — survive without it?

Dear readers — For today’s story, Laurence revisits the fascinating history of Goodison Park’s glory days ahead of Everton’s move to Bramley-Moore Dock later this year. He takes us on a journey to the storied stadium and the surrounding areas, where he asks Walton’s hospitality businesses what Everton leaving them behind might mean for their futures. This is the neighboburhood that’s hosted the team for over a century now — what’s next for this community, and indeed, what’s next for Everton?

That’s all below. But first, your Post briefing.

Your Post Briefing

Radio 1’s Big Weekend, one of the UK’s most anticipated yearly events, is heading to Sefton Park. Greg James, host of Radio 1’s Breakfast show, announced the news yesterday morning that the festival would take place in Liverpool from 23rd–25th May. Headliner Sam Fender will be joined by Wet Leg, Blossoms, Lola Young, Myles Smith and others yet to be announced. In recent years, Sefton Park has hosted the Africa Oyé festival, which has been cancelled for 2025 with its director citing infrastructure and compliance costs.

The Bishop of Liverpool, John Perumbalath, has been accused of sexually assaulting one woman and harassing a fellow bishop, Channel 4 has revealed. Bishop Perumbalath is accused of sexually assaulting a woman in the Chelmsford diocese between 2019 and 2023. A female Bishop has alleged sexual harassment by Perumbalath, but a judge refused to allow her formal complaint because more than a year had passed since the alleged harassment. Channel 4 reports that Perumbalath was also accused of sexually assaulting another woman in his previous job as bishop of Bradwell in Essex, but no charges were brought and the police closed the investigation due to insufficient evidence after interviewing him voluntarily under caution. The interim head of the Church, Archbishop Stephen Cottrell, was also made aware of the allegations before Perumbalath was formally enthroned as Bishop of Liverpool in April 2023.

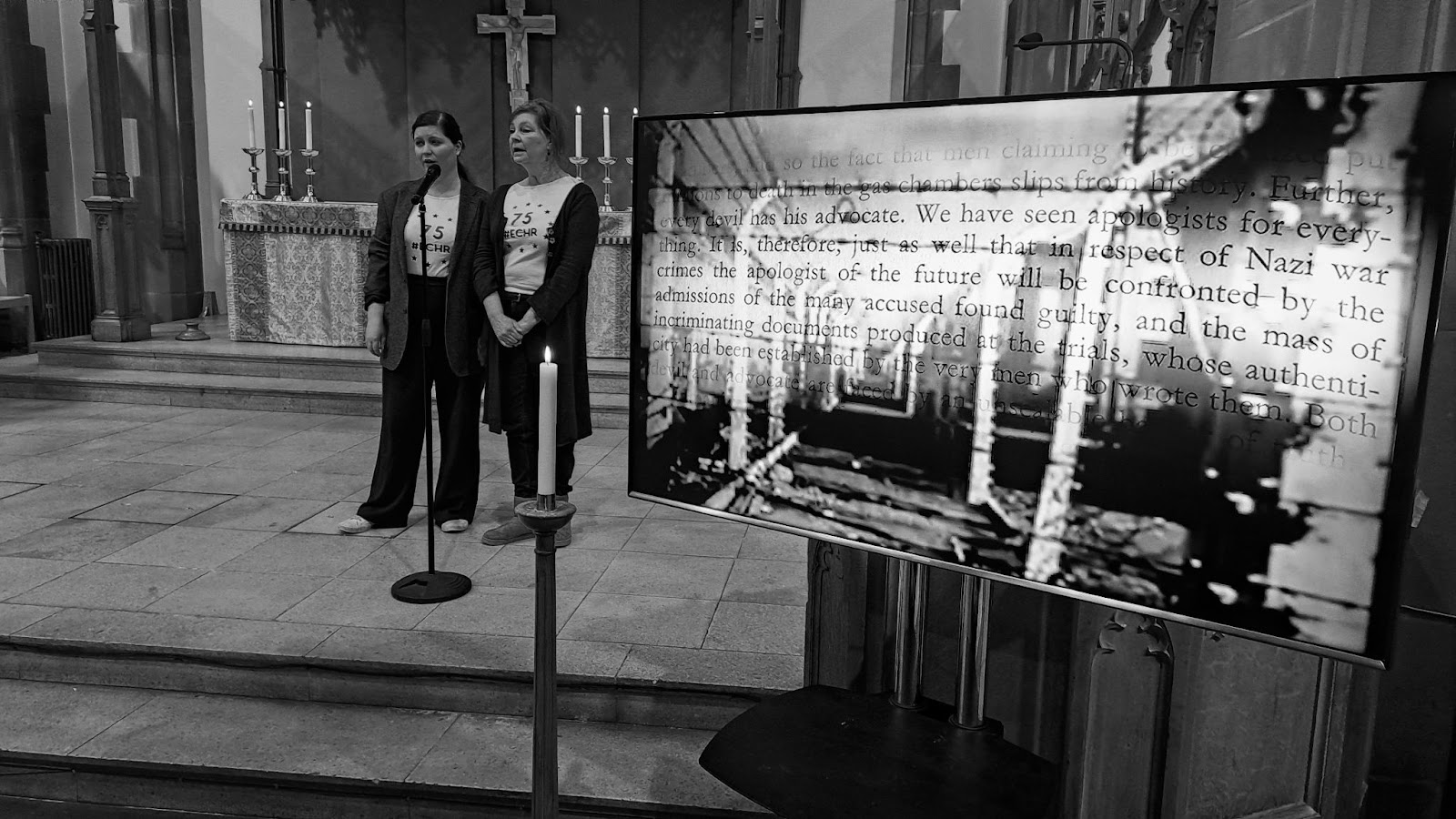

A St Helens MP who helped bring Nazi war criminals to justice has been honoured in his hometown. Hartley Shawcross was elected as Labour member for St Helens in 1945 and represented the area for thirteen years. As part of a Holocaust Memorial Day event on Monday, Lord Shawcross, who died in 2003 aged 101, was commemorated with a blue plaque at St Helens Town Hall. Meanwhile, at Liverpool Parish Church, family of Nuremberg prosecutor David Maxwell Fyfe — a Liverpool lawyer and MP for West Derby — performed their song cycle, Dreams of Peace & Freedom. As well as his service as a Nuremberg prosecutor, Maxwell Fyfe went on to draft the European Convention on Human Rights.

And a pre-school in West Derby is facing closure. West Derby Pre-School has rented Bonsall Hall for the past 35 years, their 18 staff members hosting nursery, afterschool, breakfast club, and Scouts services for over 300 families. In 2021, however, the owners, Nicola Durkin and Carmel Murphy, had to start a petition to pay for works the landlord — the Catholic Archdiocese of Liverpool — said they could not afford. In July 2024 the Church announced they were selling Bonsall Hall, leading Durkin and Murphy to set up a petition and a GoFundMe to argue for time and raise funds to potentially buy the hall. However, yesterday, Tuebrook Breckside Park councillor Joe Dunne posted on X that “despite assurances of first refusal on purchasing Bonsall Hall, the Church/Archdiocese has chosen to accept another offer – even after the preschool increased its offer to meet the £300,000 price originally suggested.” Councillor Dunne said the loss of the pre-school would be a “devastating blow to the community and to those families who depend on its services” and pledged to support the organisers’ attempt to change the Church’s decision.

Goodbye, Goodison Park

In 1966, the now-condemned Goodison Park hosted the crunch World Cup game between Portugal and then-world champions, Brazil. In fact, all three of Brazil’s group games were played at the “Grand Old Lady”, including their opener against Bulgaria, when 48,000 spectators saw both Pelé and Garrincha score in front of the Park End and Gwladys Street stands, respectively — the only fans to ever see the two legends both find the net in the same game.

But only the Portugal game featured Eusébio, the Mozambique-born sensation who would win that year’s Golden Boot as the tournament’s top scorer. With Garrincha short of match fitness and Pelé carrying an injury (and kicked off the pitch by zealous Portuguese defenders), Eusébio scored a brace and Brazil went home. My granddad was one of 62,000 fans at the game, and he said for the rest of his life it was the best match he ever saw live.

Back then, Goodison was on the up. Massive renovations to impress international visitors had meant demolishing the grand Victorian terraces behind the Park End stand. But it was already historic. Many Merseyside kids burdened with the blue-and-white Mark of Cain would grow up learning the records like stations of the rosary: the joint-first purpose-built football ground in the world; the first in England to have dugouts; the first with undersoil heating; the first to incorporate a scoreboard; the first football league ground to host an FA Cup Final; the first to host a defeat on English soil by a non-Home Nations country; the first ground to be visited by a reigning monarch, etcetera.

Everton fan Mick Ord went to his first game as a 9-year-old tagging along with his uncles in 1966 — the same year Everton won the FA Cup. He remembers a feverish atmosphere. Everton beat Coventry City 3-0, with Fred Pickering, Derek Temple, and Alex ‘the Golden Vision’ Young netting. Later, Mick would often go into the boys’ pen in the Gwladys Street stand. “You’d pay the equivalent of 5p to get in and you’d get hundreds of kids in there, all singing,” he says. “We thought we were dead loud. [If you watch] old archive film of Everton, you can hear this high-pitched noise, like a chorus of little birds in the background. That was us.”

I have happy memories of Goodison, too. Under David Moyes, Everton experienced a mini-revival in the 2000s and 2010s, and although silverware proved elusive, great games and fun nights — including against European opposition — were not unheard of. For all its limitations, the “Grand Old Lady” retains an authentic, unique, and old-world feel.

And it’s not just Everton fans who think so. After Everton’s defeat of Tottenham last weekend, lifelong Spurs fan Jah Wobble posted on X: “My favourite away ground to visit (along with Fulham). Proper old school stadium and proper fans. Still a very working-class experience.” Ex-Everton and current Spurs forward Richarlison, who scored in what will be his final appearance at Goodison Park, performed a lap of honour and later posted on Instagram: “I feel very fulfilled for all the 83 times I’ve stepped onto this pitch. Where I played the most and scored the most goals in my entire career. Today, for the last time. Thank you, Goodison Park!”

Goodison was not, of course, Everton’s first home. Famously, the team used to play at Anfield, until an acrimonious dispute with landlord, local alderman, and Conservative politician John Houlding over the rent caused the club to leave in 1892. (Like many ancient creation myths handed down from the dawn of time, that tale explains the unleashing of evil into the world — left with a stadium but no team, Houlding would go on to found Liverpool Football Club.) Goodison was in fact the team’s fourth ground in 14 years, after playing on Stanley Park opposite Houlding’s house, a site on Priory Road, the Anfield stadium, and a plot at Mere Green.

But it was Goodison with which the Toffees would become most associated. In 1892, Out of Doors magazine was stunned by its grandeur: “No single picture could take in the entire scene the ground presents,” the article marvelled. “It is so magnificently large, for it rivals the greater American baseball pitches.” (In fact, the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants would go on to play a baseball match there in 1924.) In the 1920s and 30s, the ground hosted Everton’s first true golden era, the goalscoring exploits of Dixie Dean and then Tommy Lawton leading to three league titles and an FA Cup. By the 60s, Everton’s home was a cutting-edge football stadium even before the renovations, and hosted a Toffee renaissance of two more league titles and another cup.

In the late 1890s, Walton — the area surrounding Goodison — was a growing suburb with a strong Welsh presence, heavily involved in the timber, slate and stone trades. Owen Elias and his son William Owen Elias built many streets of “Welsh houses”: rapidly assembled six-room homes. In a strangely acrostic city planning, the names of the roads facing Goodison Park spell out the men’s names: Oxton, Winslow, Eton, Neston, and so on.

But like many of Liverpool’s satellite towns, at the end of the century Walton was brought within the city limits and its fate tied to industrial decline. This was the site of Hartley’s Village, built to house workers from the Jam Factory in Aintree, closed in the early 20th century. Liverpool Inner City Zoological Park and Gardens, too, shut its doors in the 1900s. The manufacturing plant of the Moulded plastics company Dunlop struggled on until the 1980s, when a dangerous fire put paid to it. Since 1988, Everton in the Community (EitC) — the club’s highly commended charity arm — has been at the forefront of social intervention in Walton and the surrounding areas.

When Everton moves to its shining new stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock, what will happen to the afflicted but enduring community they’re leaving behind? And how much are folk memory and football history tied to — or in tension with — the material conditions of a team’s fans and the everyday people who live in these stadia’s shadows?

If you know your history…

“Mediocre,” my dad tells me when I ask him to sum 1970s Everton up. “But with occasional joy.”

His dad — my granddad, the same who saw Pelé, Garrincha, and Eusébio grace Goodison’s hallowed pitch in ‘66 — died on the 30th January, 1975, fifty years ago today. “My uncle Jack got hold of a season ticket and used to take me,” Dad says. “That was a great solace.”

Everton’s second renaissance came in the 1980s, which included Goodison’s greatest ever game: a 3-1 win over Bayern Munch en route to European silverware. Fan John Burton, then 14 years old, fondly remembers Everton’s double-winning ‘84-’85 season — perhaps for the wrong reasons.

“I was playing at the pitch at night, and the caretaker used to come on and chase us off,” he says. “And you know at the Park End where you’ve got the big blue door and then the little door inside? Well, he left his keys in there.” He pictures the moment: “I remember [the caretaker] had a beige mac on, and it was like slow motion. He was going, ‘Nooo!’ and I was going, ‘Yeah!’”

John came back the next night before the staff could change the locks, and he found the master key. When word got out, “I used to have loads of people waiting for me by [St Luke’s Church]. I used to let about five, six hundred people in every home game. I’d make about three to five hundred quid...”

Latest

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

The Pool of Life

Goodbye, Goodison Park

Everton’s historic stadium has been at the heart of the community for 13 decades. Can the local area — and Everton itself — survive without it?