'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Eric Griffiths upset novelists, insulted academics, and reduced Thatcher’s speechwriter to tears. But he died in relative obscurity.

They used to say that if you remember the 1960s, you weren’t really there. For the following generation, that was the 1990s. The drugs weren’t as psychedelic, the pop bands less ambitious, the feminist wave more conciliatory and the 'revolution' closer to a shuffling of HR personnel. But the heady atmosphere of Britpop, Blair and 'Cool Britannia' sweeping away Conservatives and the rigid class system was surely as intoxicating as any LSD trip or sitar solo, dislocating you from social status, identity, and good sense.

This brave new world was the setting for a national scandal in 1997. In a Cambridge admissions office, 17-year-old Tracy Playle from Harlow, hoping to read English at Trinity College, instead encountered her nemesis: irascible Cambridge don Eric Griffiths.

Griffiths had been at Cambridge for the better part of three decades. Perhaps, like a prison lifer, he had become institutionalised. Maybe, as some would speculate, he was simply drunk. Whatever: Griffiths belittled Playle, parodying her Essex accent, accusing her of talking “gibberish”, and taking for granted she could not read the “funny squiggles” of Ancient Greek.

She couldn’t, to be fair. But this, in 1997, would not do. We had not voted out John Major’s clique of toffs for nothing (actually, in Major’s case at least, not all that toffy, but I digress). A clearer allegory for post-Tory Britain could scarcely be imagined: here was a young female striver, running up against a chilly male symbol of the ancien régime. Sniffing the zeitgeist, The Daily Mail got hold of the story the following year and plastered Playle’s face across the front page. This was during the regrettable historical interregnum between the medieval stocks and social media, so Griffiths was pilloried in the press. Despite the furore, Cambridge did not fire him, but he was never again asked to be part of the admissions process.

In his hour of need, Griffiths had one champion: his mum. Eric was not, she protested, an upper-class snob. In fact, he came from a more disadvantaged social rung than the suburbanite Playles; Mrs Griffiths was a former shop worker from Liverpool. This did little to dissuade the media mob: even those who granted that Griffiths may have been “overcompensating” for the prejudice he himself may have suffered deemed him “obviously a prat”.

In 2018 — two decades after the scandal — Griffiths died, aged 65. He had been silent for seven years; a stroke had robbed him of his voice and forced an early retirement from lecturing. Tributes and reminiscences followed: The Guardian had once named him “the cleverest man in England”; a poet he’d disrespected had called him “the rudest man in the kingdom”. In 2019, Trinity College uploaded a memorial to YouTube that ran for two and a half hours, with eulogies and readings from the likes of adventurer Hugh Thomson, and actor Simon Russell Beale, both of whom Griffiths had taught and inspired.

The praise far outweighed Griffiths' published output. In his lifetime, he only had one book to his name: The Printed Voice of Victorian Poetry. Yet his renown was widespread — and notorious. On his website, Thomson referenced Griffiths’ “slightly dark reputation” and “wild side”, while pre-eminent literary scholar Jonathan Bate wrote in the Times Literary Supplement that Griffiths “attracted groupies and opprobrium in equal measure”. Just who was he?

From Walton to Walter Raleigh

Griffiths was born in Liverpool in 1953. His mother, Mary Kate, was a shop assistant, while his father, Stanley, worked on the docks; before World War II he had toiled in a North Wales slate quarry. Both spoke Welsh as a first language — not unusual in Walton, where Eric attended Florence Melly primary school on Bushey Road. According to his Times obituary, the school-age Eric was “prodigiously catty” and encouraged to read widely by his parents. He won a scholarship to the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys, the alma mater of George Harrison and Paul McCartney. (In case you were wondering, this is not the Eric Griffiths that Harrison, McCartney and John Lennon played with in the Quarrymen.)

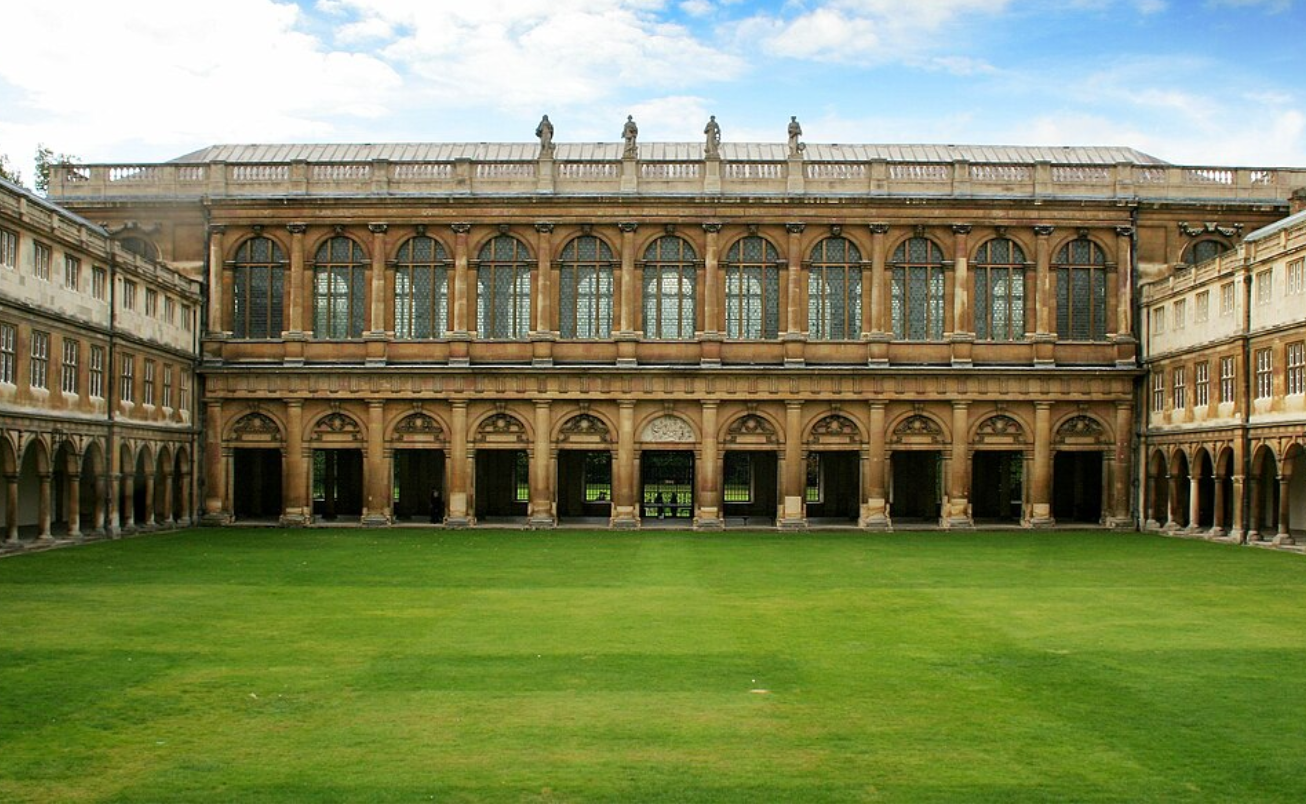

Then in 1971 came Pembroke College, Cambridge, again on a scholarship. Although the working class Liverpool lad was conscious of not belonging, he was “a daunting student to teach”, Clive Smith, two years ahead of him at Pembroke, noted. But Griffiths soared, soon taking a research fellowship at Christ’s College under distinguished literary critic Christopher Ricks.

Bate first encountered Griffiths then, noting that his “northern vowels” had acquired “a Cambridge suavity”. Responding to a lecture Griffiths gave, Bate offered an observation about “Mallarmé’s idea of the elocutionary disappearance of the poet”. Bate later wrote that “Griffiths told me that I was talking bollocks.”

In 1980, Griffiths submitted his thesis — a study of TS Eliot, WB Yeats and Ezra Pound. A teaching fellowship at Trinity College immediately followed. Eventually, Griffiths earned the name “Reckless Eric” from his students, his lectures admired for their wit, cleverness and refusal to discriminate against “low” culture, discourses on Shakespeare punctuated with references to Eastenders and Doctor Who (he would later set an exam question comparing Amy Winehouse’s ‘Love Is a Losing Game’ with a ballad by Walter Raleigh).

According to colleague John Mullan, Griffiths would sip a "mysterious liquid” through these orations, thought to be whisky. For a time, his lectures featured in the entertainment listings of a student newspaper. Among a constellation of star lecturers around this time, Mullan remembered hard-drinking, Armani-sporting Griffiths as “the top performer”.

In the 1980s, Griffiths also became a TV and radio personality, making a television programme about Talking Heads and appearing on late-night arts shows. A busy decade: he also found time to write and publish The Printed Voice, convert to Catholicism after seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary, and consume so much gin that the entire ten years disappeared from his memory. His promising televisual career was cut short when he reduced author AS Byatt to tears by describing her Booker Prize-winning Possession as “the kind of novel I’d write if I didn’t know I couldn’t write novels”.

Nobody — not decorated novelists, fellow lecturers, nor bright-eyed students — was safe from his corrosive tongue. In an entertaining exchange of letters in the LRB from 1985, Griffiths takes two “despicable” critics to task for the crime of (in his eyes) disrespecting the poet Geoffrey Hill — like Griffiths, a high achiever from a working-class family. Griffiths ends this on a strange note:

“I have never been and never will be a member of the Anglican Church, [...] I still speak on and off with a flat, Northern ‘a’, and [...] I would never vote Conservative in any election, any more than I would ever support Everton Football Club.”

Interested in how Griffiths’ origins played into his identity, I reach out to Christopher Ricks, now 91 and living in Massachusetts. Listening to him over Zoom, you would never guess the “greatest living literary critic” – as John Carey once described Ricks – was a nonagenarian. His fluidity of thought and powers of recall are intimidating. Although hard of hearing, he has no problem navigating my tangled, rambling questions.

“It’s something [Eric] joked often about,” Ricks says when I ask him about Griffiths’ Liverpool roots. “Which does not mean it was not important to him. Often jokes serve as a helpful protection.”

I also chat to former student Freya Johnston by phone. She was responsible for the second book technically authored by Griffiths': If Not Critical, a collection of his lectures released just before his death, edited by Johnston.

“Just from speaking to him, I wouldn’t have known [Eric] was from Liverpool,” she tells me when I mention Griffiths’ “northern” vowels.

Johnston knew Griffiths later than Jonathan Bate did; perhaps he had fully shorn the Scouse twang by then. Or perhaps Bate, having married a Scouser, simply has a keener ear for those vowels. Listening closely to BBC clips of Griffiths on YouTube, I have to confess I lean towards agreeing with Johnston; my wife, who is originally from Fairfield, concurs with Bate that this is someone disguising the fact they’re from Liverpool. In any case, “I wouldn't have said that [Liverpool] was as prominent a part of his identity as, for instance, being gay was,” Johnston says.

Griffiths later returned to Liverpool at Bate’s invitation, delivered a “dazzling” lecture on Beckett, and “spoke of his joy in coming home, of how he always felt like an outsider in Cambridge”. But there’s a long tradition of gay men born here for whom Liverpool was either an ambiguous blessing or something to be transcended: Clive Barker; Terence Davies; Chris Bernard; a beloved uncle of mine. Several — Griffiths included — adopted the Wildean ideal of a rapier wit, attacking so profoundly that defence would never be necessary.

Ricks tells me a story of walking with Griffiths in Cambridge one night. Ricks, the master, had opined “that literary criticism very rarely — except with Dr Johnson — achieved the standing of art itself”. Griffiths’ insistence that The Printed Voice of Victorian Poetry had also ventured into the arena of art did not meet with Ricks’ agreement.

“An American historian called Wallace McCaffrey passed us in the street,” Ricks says, “and when we had gone by, Eric said, ‘Stupid shit.’

“He's not stupid,” Ricks patiently replied, “He’s very nice and courteous, and I was pleased to see him.”

“Not McCaffrey,” Eric said. “You.’”

Ricks tells this tale “full of love for Eric.” But he was far from the last distinguished scholar to feel Griffiths’ heat. Columnist Nicholas Lezard, a student of Griffiths’, once witnessed Griffiths reduce Norman Stone, the daunting historian and advisor to Margaret Thatcher, to tears. In 2005, Griffiths co-edited Dante in English, which includes his 100-page introduction — perhaps the closest thing to a book-length essay he ever completed after The Printed Voice.

It’s a dizzying achievement, dense with observations, jokes, allusions and judgments; Ricks would later call it “amazingly convincing”. Someone who wasn’t impressed was American literary critic Helen Vendler, who expressed disapproval at Griffiths “jazz[ing Dante] up in contemporary slang” in an LRB review. (In her introduction to If Not Critical, Johnston seems to agree that this vernacular slumming was an unfortunate tendency of Griffiths’.).

“Helen Vendler does not like the way I write”, Griffiths responded. “I in my turn deplore the way she reads.” In an exacting letter, Griffiths corrects the great Vendler’s “incomprehension” as if she were an uppity student, ending with: “Vendler fears that I will think her ‘humourless and pedantic’. Let me assure her that nobody could accuse her of pedantry.”

Potential unfulfilled?

I don’t have the heart to ask Ricks or Johnston whether their dear colleague was an underachiever (I also can’t find The Printed Voice for less than £100 to judge whether it was indeed art). Few doubted Griffiths’ intelligence: he read intensely in French, German and Italian, as well as English. Was his acidic disposition a product of class (self-)consciousness, or of unrealised talent? His Times obit calls him the victim of his own high standards; he felt increasingly “encumbered” by the fear that a second book was beyond him. Some years ago, writer Benjamin Ramm tweeted that, “After failing to fulfil his early potential, [Griffiths] opted to specialise in savage 'wit', which intimidated others and isolated him.”

But despite his withering temperament, Griffiths’ former students remember him approvingly. Many accompanied him on European holidays, where he indulged his obsession with photographing romanesque churches. (Perhaps sensing another scandal incoming, he withdrew from students in his later years).

Novelist Sameer Rahim, initially discouraged from attending Trinity after the Playle incident because “big, bad Dr Griffiths taught there”, wrote that If Not Critical showed “a generous spirit in full flow”. Jessica Martin, now canon of Ely Cathedral, saw a counterintuitively democratic dimension to his relentlessly acerbic nature: “if you were not up for the project of absolute attention, or too ready to hide behind convention, or fashion, or guesswork, he would demolish every fragile defence you had until you saw something truer.” (Emphasis mine).

Griffiths could also be very kind: when one student returned to Trinity after a year off following a suicide attempt, Griffiths took her under his wing and even lent her money to cover medical expenses.

What of Playle? In 2001, she graduated with a first-class degree from Warwick and wrote a crowing op-ed in The Guardian. Now, she runs a consultancy business, helping “individuals to find power, confidence and meaning in their careers and personal lives”. As far as I know, she never did learn Ancient Greek.

Although Griffiths published “much less than might have been expected”, as Johnston admits, If Not Critical was a hit. It’s rare “for an academic book to sell 1,000 copies,” Johnston says. “It sold out of its first print run immediately”.

But for whatever reason, Oxford University Press has shown no interest in a follow-up. Liverpool University Press, which Johnston approached because of Griffiths’ connection with the city, also passed. Johnston, who feels “terribly burdened” by her garage full of Griffiths’ unpublished writings, is understandably frustrated.

After Oscar Wilde’s death, his friend Robbie Ross said, “his personality and conversation were far more wonderful than anything he wrote, so that his written works give only a pale reflection of his power”. Griffiths’ works are scanter still. Sometimes, his Catholic obsessions, immoderate personality and the Dantescan fate of losing his celebrated voice make him feel more like a character in an Evelyn Waugh book than a real person (Johnston says several writers have tried to incorporate him into their fiction, with little success).

Perhaps, despite Ricks’ fond remembrances and Johnston’s sterling efforts, his contributions will remain likewise ephemeral. Griffiths’ career and life recede into memory; those memories in turn are lost. As Ross wrote of Wilde, “it will be impossible to reproduce what is gone forever.”

Comments

Latest

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Why are Merseyside’s state-of-the-art hydrogen buses stuck in a yard outside Sheffield?

I was searching for my identity in a bowl of scouse, and looking in the wrong place

The Pool of Life

'The cleverest man in England' was from Liverpool. Did it hold him back?

Eric Griffiths upset novelists, insulted academics, and reduced Thatcher’s speechwriter to tears. But he died in relative obscurity.