Come for the music, stay for the education: Annie, Geoff and Probe Records

Profit was beside the point; Captain Beefheart reigned supreme and stilettos were worn in muddy Yorkshire fields

Dear readers — in the last month, Liverpool has lost two of its most influential icons. Annie and Geoff Davies, co-founders of Probe Records — one of those venues you would enter as a wayward teen and leave an enlightened mind (after a swift dressing down about your previously sub-par music tastes) — died within two weeks of each other, a few weeks ago. They divorced way back in 1986, splitting the record shop (Annie’s) and the label (Geoff’s) but through Probe their enormous legacies are intertwined, as well as individual. Today’s piece is an ode to both.

Normally Thursday’s edition of The Post would only be sent out in full to our paying members, but with today’s piece that didn’t feel appropriate. We wanted everyone on our list to read about the lives of these two very special people, and so we’re sending it out to all 17,000 of you. We hope you'll jump into the comments with your own memories of Annie and Geoff.

If you are not a paying member, we ask you to consider joining us today anyway. Why? Because our journalism isn’t free to produce. If you think Liverpool is better if it has journalists writing in-depth essays on subjects you think are important, you have to pay for it — and at £7 a month, it’s less than a couple of pints. So if you’re not a member, please support the Post by hitting the button below.

Your Post briefing

Parents who have suffered at the hands of Sefton Council’s children's services have laid children’s footwear outside a meeting of the department, urging them to "walk a mile in their shoes”. Back in May we published How Sefton failed its most vulnerable children, setting out the stark failings of the department. We’ve uncovered that children have been separated from their families for years due to failures to swiftly enact court proceedings, that there was enormous staff turnover in the department, we’ve seen children essentially locked out of the education system due to incompetence and reported one incident in which the council sent two teenage neighbours into the home of a mother to assess her parenting skills. The service is in special measures due to serious safeguarding concerns. David Moorhead, the chairman of Voice of the Families — a group representing parents who feel they have been let down — said: "They've had years to improve and they just haven't. We represent 250 families who feel broken and destroyed."

West Derby MP Ian Byrne wants the Football Association to call for UEFA president Aleksander Ceferin to “consider his position” over alleged cronyism and safety deficiencies in the wake of the 2022 Champions League final. As a subsequent report found, the final — between Liverpool and Real Madrid in Paris — was a near-catastrophe, with thousands of supporters suffering due to a “failed safety management operation, hours of static queues, dangerous policing and attacks by local thugs”. A UEFA-appointed review panel made 21 recommendations for future improvement, but Byrne believes things should be taken further. He wrote to FA chief executive Mark Bullingham saying the appointment of Zeljko Pavlica as UEFA’s head of safety and security was “cronyism”, adding that it was “a position he was patently unfit to fill”. Pavlica is Ceferin’s best friend and got the job after Ceferin became UEFA president in 2016.

City Region metro mayor Steve Rotheram will meet with Everton’s prospective owners 777 Partners to get assurances over their plans for the Bramley-Moore Dock stadium. Should the construction falter, Rotheram told BBC Radio Merseyside, there would be serious “ramifications” for the regeneration of the whole of north Liverpool. The £760-million ground (a cost that has risen significantly) is due to be completed in late 2024. “Everton is the catalyst for the renaissance of that whole area of the city,” Rotheram said. “That area has been crying out for the opportunity to pull itself up, the project gives an opportunity for the redevelopment of that whole area.”

It was 1989 and Half Man Half Biscuit needed a star for their new music video for “Dickie Davies Eyes”. Annie Davies, the co-founder of the iconic Probe Records, which spawned the band’s Probe Plus label, had been roped in for a starring role.

The original plan, that she’d play the “sultry temptress from the Cadbury’s flake advert”, wandering through a cornfield in soft focus (as the lyrics go: “God I could murder a Cadbury's flake, / but then I guess you wouldn't let me into heaven”), was one she jumped at, recalls David Lloyd, who played in the band in the 80s. But when she arrived the goalposts had shifted. They now also needed someone to play a less glamorous role: the eponymous sports presenter himself; Dickie Davies, complete with a bushy grey moustache. She jumped at that role too — even adding a grey streak to her auburn hair. “She actually made a fantastic Dickie Davies/Cadbury’s flake beauty,” David says.

“That was the thing with Annie,” he continues. “She was fierce and really didn’t give a shit what people thought about her because she owned every space she was in”. The record went to number one in the indie charts and stayed there for 12 weeks. So every Saturday morning on ITV for three months, broadcast to the nation, was Annie Davies, standing moustachioed in a field in Thursaston.

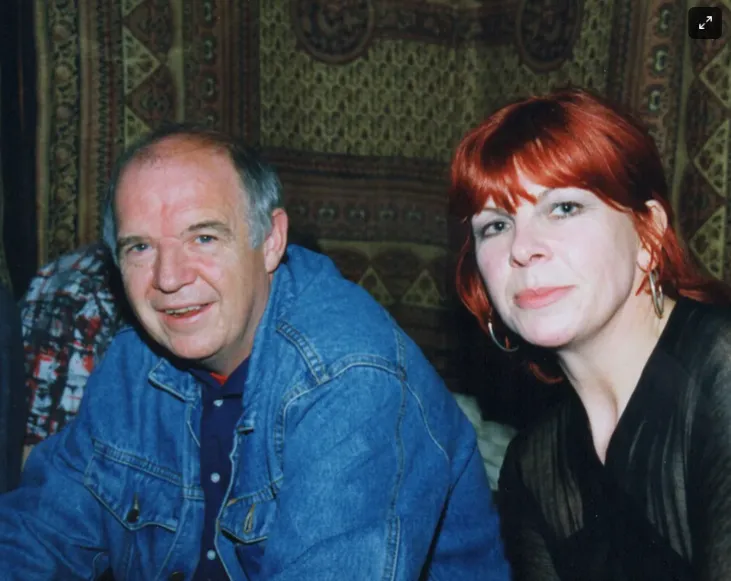

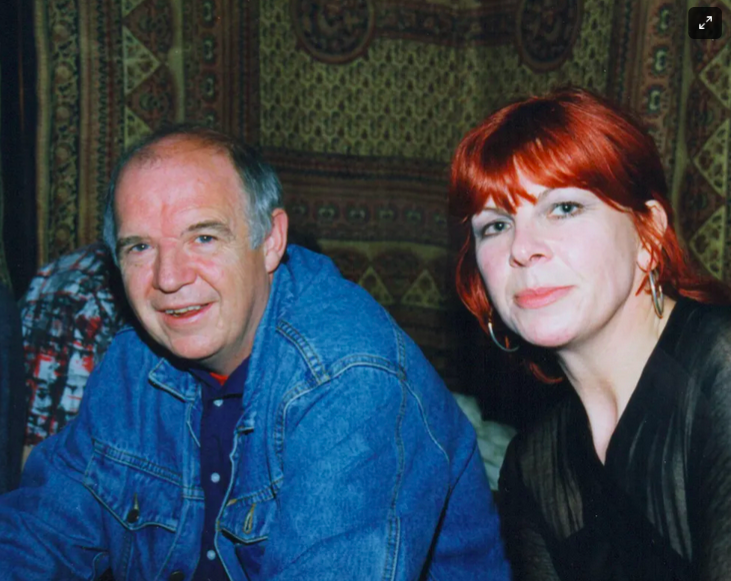

Last month, Annie Davies passed away at the age of 76. By some bizarre cosmic coincidence, her ex-husband Geoff — with whom she co-founded Probe — passed away too a couple of weeks later. He was 80. Geoff was the better-known name of the two, the Godfather of the Liverpool music scene to many, a man whose own tastes generally became everyone’s soon enough. But though they split in 1986, Probe was a joint enterprise, and its massive legacy is shared in equal parts between them.

The last couple of weeks have seen a tidal wave of tributes. The way Geoff single-handedly transformed Liverpool through his unwavering insistence that every man, woman or child who passed through his shop left with a copy of Love’s Forever Changes, as well as assorted Captain Beefheart records. “Bought [Captain Beefheart’s album] Clear Spot there when I was 13,” recalled the music writer Andrew Male. “A delighted Geoff asked how old I was, then told the whole shop”.

If you’ve ever read Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity, you’ll be familiar with the character of the record shop owner as a wannabe tastemaker. It’s a cliché for a reason: the sort of music enthusiast who lectures all who enter their shop and wards off those whose philistine taste doesn’t make the cut. Such a person might be less concerned by how much money sits in the till at the end of the day. “Money didn’t prove to be a big winner with Probe,” laughs Norman Killon, who worked there for the best part of the 70s. But that was besides the point anyway: if they ever made any profit, it was almost a shock.

And by all accounts there was at least a touch of High Fidelity (long before High Fidelity was even a thing) to Probe. “Everyone,” wrote author Frank Cottrell-Boyce, “had a story about Geoff chasing them out of the shop for asking for the wrong kind of record”. But Geoff Davies wasn’t a wannabe anything. He was a bona fide tastemaker in Liverpool. Someone whose life was in service to music, and whose service to music pathed the way for so many others. “Probe was the gateway to enlightenment,” wrote screenwriter Kevin Sampson.

Just getting the records in the first place was an art. Killon dealt with importers in America, and for want of a home phone would find himself loitering in a phone box just before midnight whenever it was delivery day. The records would be flown into Heathrow, opened by a man at the airport who would then call Killon and list off whatever he found in the box. There was a fair amount of guesswork involved: I’ll have one of those, a couple of those. The next morning they’d arrive at Lime Street and Geoff and Norman would play them one by one before the DJs arrived to scuttle off with whatever pricked their ears.

Being a tastemaker isn’t quite a lottery, but neither is it a perfect science. Sometimes they went for records by nobodies who would soon be somebodies and Geoff was the oracle. Other times those nobodies remained firmly in the nobodies camp, for good reason.

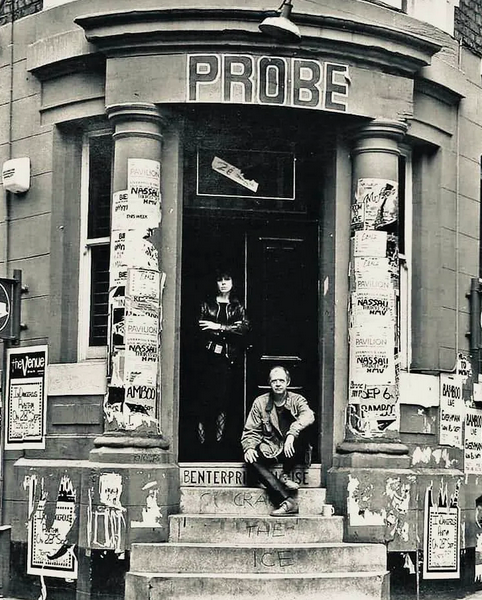

The first Probe Records opened on Clarence Street in 1971, but its iconic address, the one people remember, on Button Street, came first years later in 1976, with the collage of tearing gig posters on its thick pillars framing the door and the words PROBE in big block capitals above it. Below, the grand steps leading up to the entrance, as if to symbolise the ascension from skinny tasteless teenager to an enlightened mind.

Annie kept more in the background at Probe, but after she and Geoff split in 1986 she took on the shop by herself, with him getting the record label. It’s survived to this day. “It was extremely unusual for a woman to run an indie record shop, let alone keep going for 50 years,” says her long-time friend and former BBC Radio Merseyside presenter Christine Ruth.

Christine met Annie after she moved to Liverpool in the late 70s. They were part of the same scene. Nights out following upstart bands all over the north, charging through muddy fields in Yorkshire in stilettos in the evening, then back to Eric’s at night to see the last act on stage. “She was very loyal, everyone who came in touch with Annie became immensely loyal to her,” Christine says. “And charming. Although she was shy, she could light up a room”.

But as well as the charm, and the style (she was often mistaken for Chrissie Hynde), and the loyalty she attracted, she had a quiet business acumen too. Businesses in Liverpool in the 80s were dropping like flies, and Probe’s staying power was the exception, not the rule. “To have kept it going through the absolute doldrums of Liverpool’s financial situation was a remarkable achievement really,” Christine says.

The lack of actual wealth was offset against the artistic richness of the scene Probe came to inhabit. It was already happening in theatre with the Everyman, the Liverpool poets, the massive arts scene, but Probe became an essential tenet of that too. “All the music coming in through the docks that inspired the Beatles,” Christine says. “They channelled that energy.” Alongside Eric’s, the club/gig venue a few yards away with which Probe shared a kind of symbiotic bond, a minor universe of creative talent existed; from Echo and the Bunnymen to The Teardrop Explodes (whose frontman Julian Cope even worked in Probe selling records). The music writer Paul Du Noyer would call it the “the semi-official control room of Liverpool music”.

Geoff meanwhile took Probe Plus forward, and Half Man Half Biscuit — the satirical and often surreal rock band led by Nigel Blackwell — was their lodestar. In fact, when Blackwell took an extended break after the success of “Dickie Davies Eyes”, Geoff found himself dodging the bailiffs, as he recalled in a 2011 interview with The Quietus. But he cared about all the music put out on Probe Plus, it was never a money thing. Every act had its place in the Probe Plus ecosystem.

His taste wove in and out of the eras, an old “Cavernite” in the 60s along with Annie (who proudly owned a photo signed by all four Beatles of them in their leathers) he moved through the hippie years and beyond, but was never confined by the winds of change either. Punk might have been the making of Probe, but inside you could find the Ramones sitting along Aboriginal nose flutes. That was the magic.

He might’ve been a man with little time for crap music, but those who knew him remember the kindness that sat behind it. And he was funny — brutally funny. In fact, Norman only ever saw him truly angry once, when two men chased Pete Burns — the androgynously-dressed former Probe employee and later famous Dead or Alive singer — towards the shop, having “taken umbrage” at his unique appearance. Geoff seized the big metal bar they used to lock the front doors and the two men didn’t stick around.

In the scenes that matter, it’s not just about the right timing — the right people are everything, too. Annie and Geoff, in their own ways, were that. A whole generation of music lovers in Liverpool would have grown up differently without them. At the very least, their record collections would have been more embarrassing.

Comments

Latest

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Come for the music, stay for the education: Annie, Geoff and Probe Records

Profit was beside the point; Captain Beefheart reigned supreme and stilettos were worn in muddy Yorkshire fields